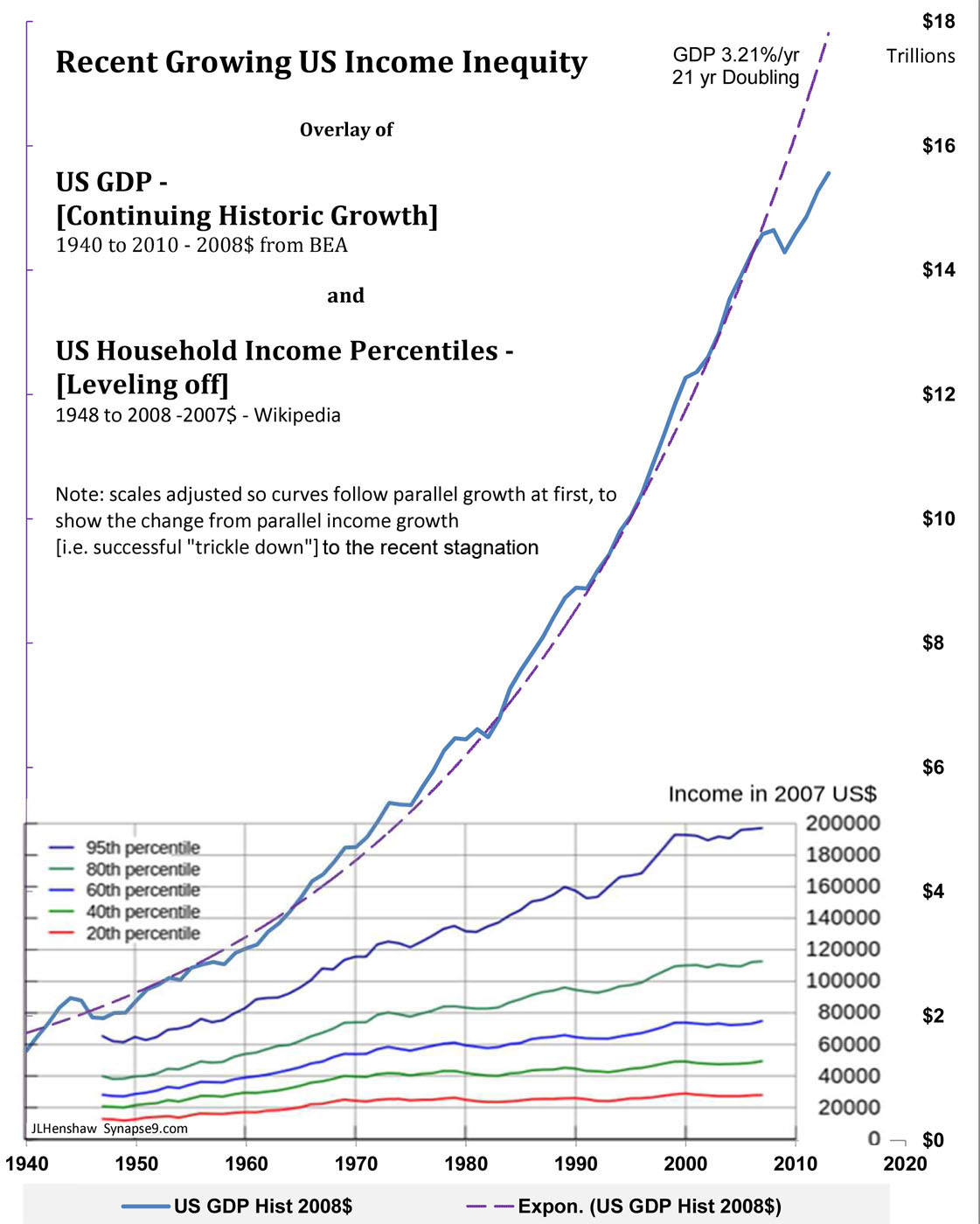

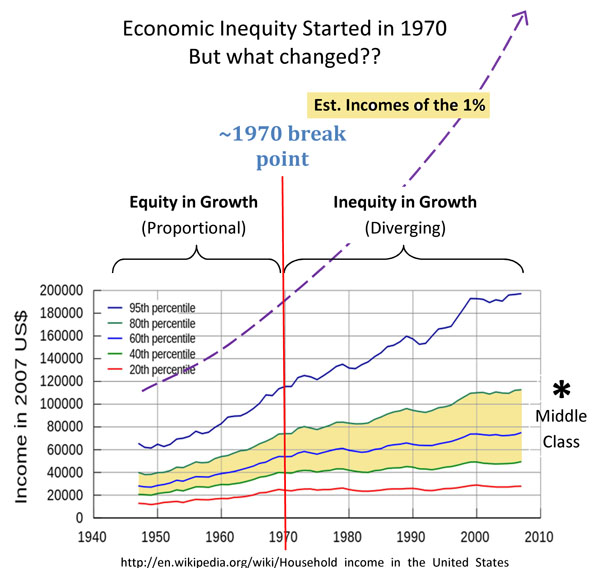

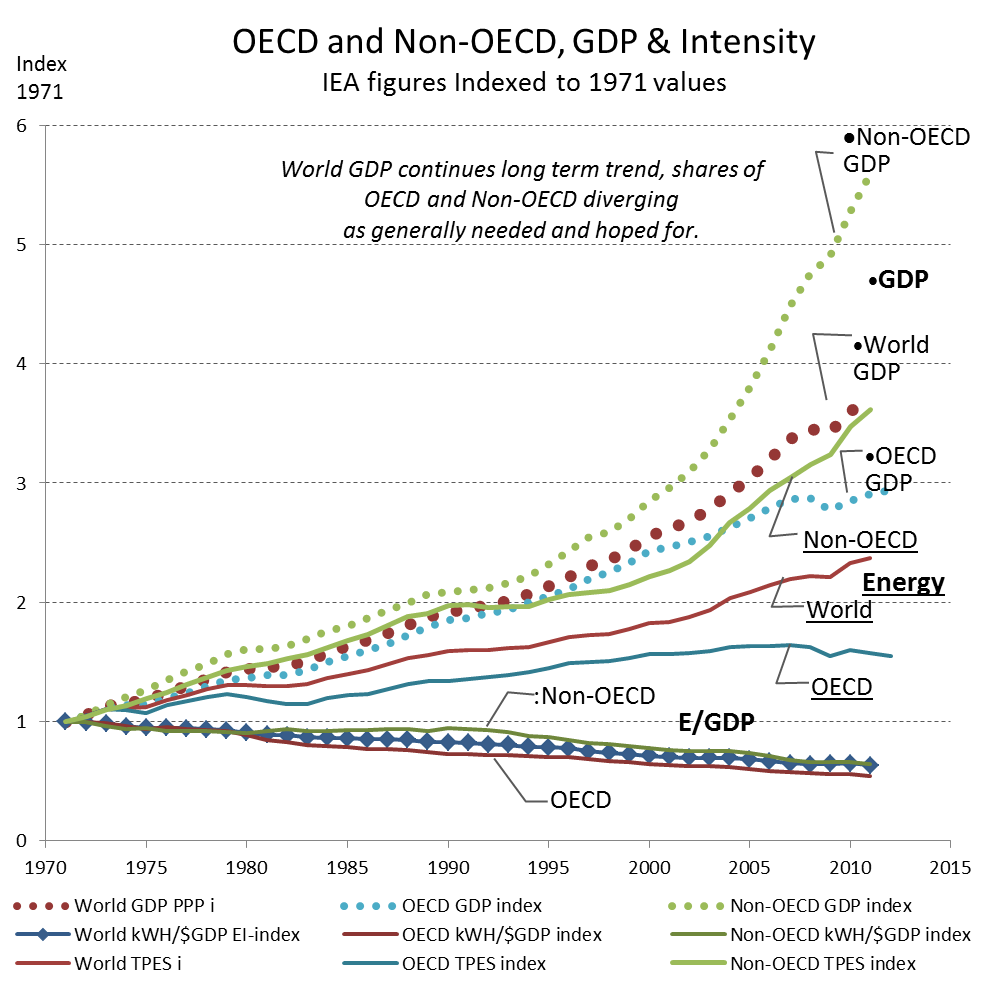

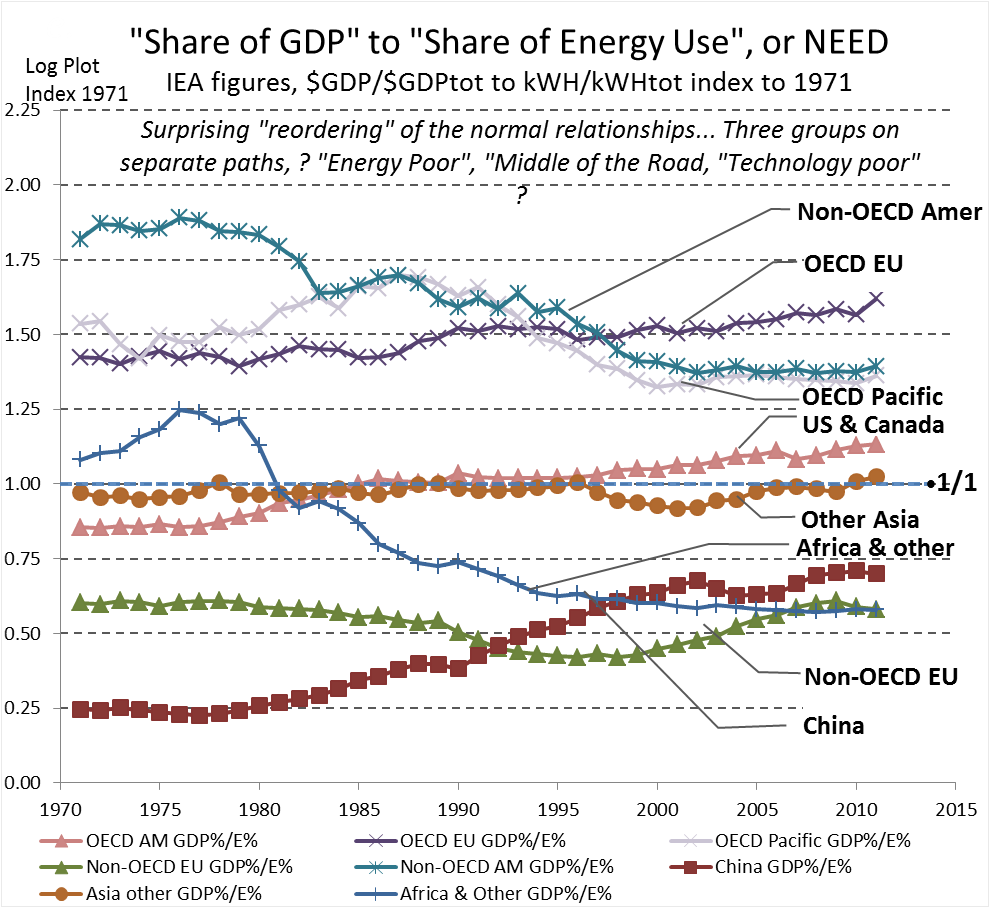

- ed note: The current discussion of the core dilemma of capitalism, as a limitless system for creating growing wealth, is in terms of the crises we now face caused by it, producing socially disruptive innovation and growing financial inequity. Those include 1) threats of rapidly growing social inequity, 2) unsustainable national and private debt, 3) disruptive scales of job loss from globalization and automation, 4) demands for unachievable ever faster and ever more complex learning and change , 5) the rapid depletion of earth’s resources, 6) disruption of the climate and earth’s ecologies, and of course 7) increasing international conflicts between conflicting economic interests, and of course, 8) growing risks of grand scale financial collapses due to failing promises, as a kind of general list. It’s quite a list. There’s been a very long debate but mostly scattered in pieces and hidden from view. That’s both because the primary culprit is our whole way of life, naturally hard to talk about, and what to do with “money” .

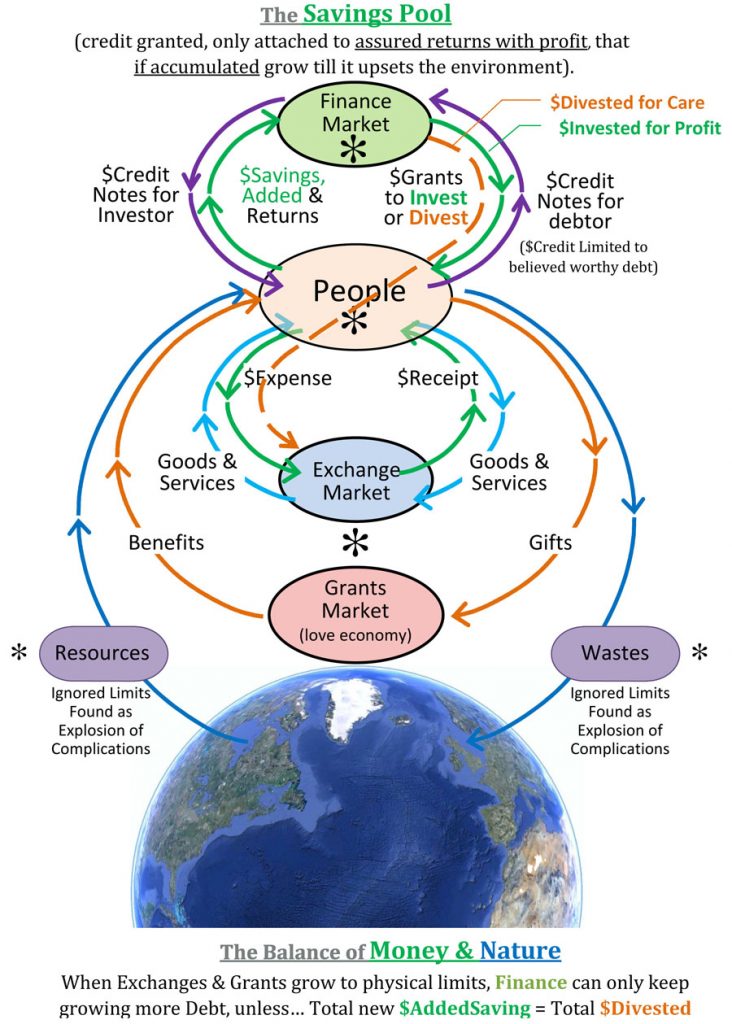

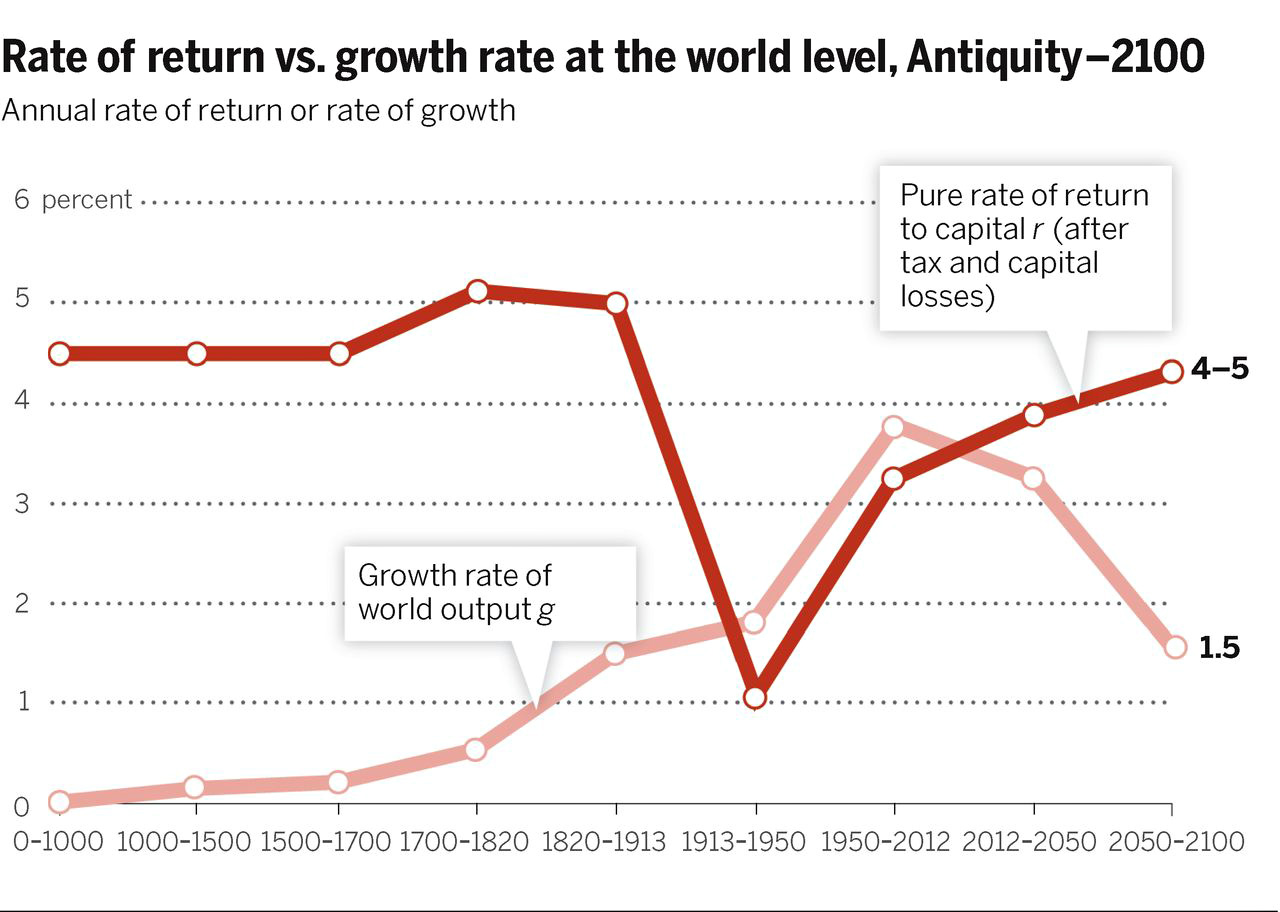

- The design of our economic system that defines “capitalism” is very simple. It’s “the use of investment profits to build up investments”. That’s it. Why such a simple practice has a hold on us is that it promises both society and individuals ever faster growing profits without growing work. Of course that tends to end up badly, having been much too good to be true from the start. The equally simple design of all natural systems is that “any system needs to build up to get started, and then stop building up to continue”. The two definitions conflict. Keynes and Boulding foresaw that the two would come to blows, once the economic system had built up and needed to stop building up to continue. They saw capitalism could become like a natural system and can change only if investors spend their profits. The sense of it is that investors would “pay it forward” so their profits would take care of the future rather that keep “paying it back” so old money could take ever more from the future. It would let our economic system first build up, and then stop building up, to be able to continue, with no guarantees but as a possible path forward. It’s all too simple as a design problem, as how all enduring natural systems develop and needs the social principle to make sense. The dilemma is completely unsolvable as a financial problem within capitalism, though, challenging our whole way of life as a rather immediate concern. jlh 3/14/16

____________

_____________

from a 21st century view……

Your question is, do we all use our profits to extract increasing pay back from others,

building up an ever growing drain on what makes our world profitable?

______

Or do we pay our profits forward to assure our world remains healthy

to grow our own ideals, our families, our communities and our world,

treating profits as a gift to what matters?

______________

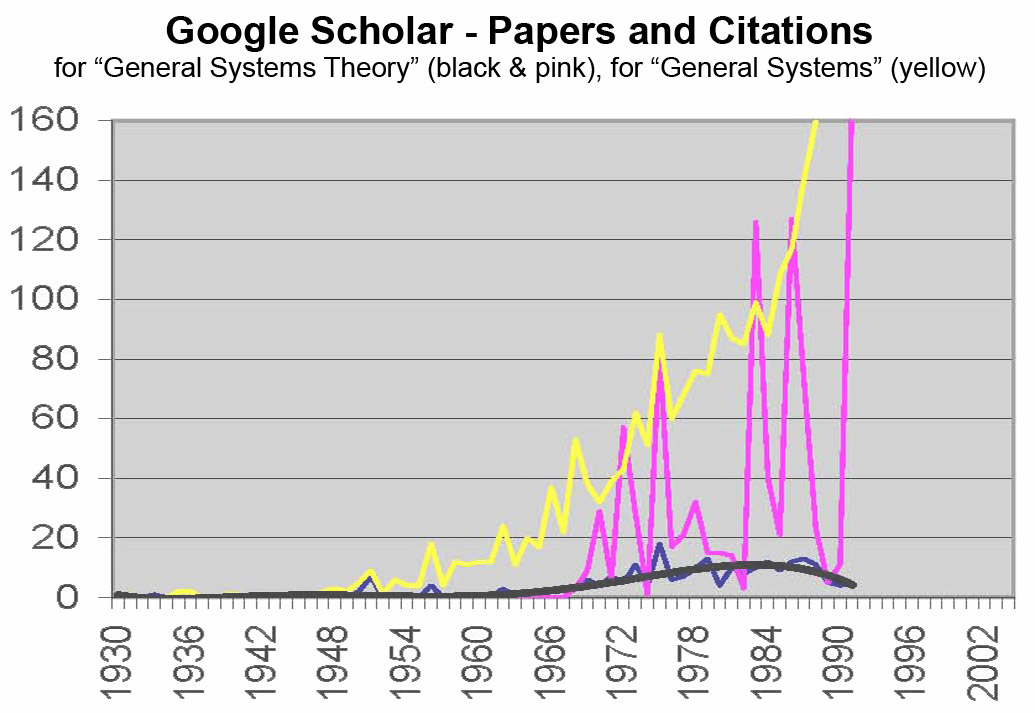

J.M. Keynes and Ken Boulding were early and mid 20th century “whole system thinkers”. They were true geniuses, struggling for words to convey how complex systems with all independent parts work as a whole somehow. It’s truly the profound puzzle of nature, how illogical it is that all the independent parts of systems would act as if they were all coordinated. They didn’t stop at just looking for simple rules of prediction having no idea where they came from or when they might change. They also looked for and found elementally simple organizing principles of design, for how the parts of market economies coordinated with each other as whole systems and what drove them, central principles they weren’t able to communicate and that have yet to be appreciated at all. From their views they did each say that:

the world economy would soon bankrupt itself by over-investment,

as a natural limit to unlimited financial growth,

due to the central driving financial practice of compound investment

Each was also a expansive thinker with their own ways of speaking about broad principles, so they are hard to read too. It’s only by learning to think about the economy as a whole system, with all its parts working together, and distributing its surpluses and shortages throughout all its connections, that you can piece together from their writings the common finger prints for the above simple principle as what they were clearly saying.

I had some extra help with it, though. I learned of Keynes’ work on the natural limits of finance from speaking with Ken, having gotten a chance to ask him in person, if he knew of any economists who had studied the limits of compound investment as a natural limit to growth. I had asked Ken about it in 1983, and was able to understand what he said on the subject, because I had been searching for a few years already for anyone else who had discovered the principle, that growth systems, if not interfered with, would naturally upset their own conditions for growth. It’s a completely invariant natural principle. Continue reading Did Keynes & Boulding both really say that?