…and the laws that move you from maximizing power to maximizing resilience.

Like many young college women Kepler awoke that morning with other things on her mind than the project she had planned for the day. She had been dreaming about how she loved her drawers of personal things, in colorful piles, neatly rolled, in little bags and folded, each in its own style and fit together. Maybe she would become a “collector”, she thought, they gave her such a thrill. How nature was “quite a collector” too fascinated her too, creating all the natural world’s very special arrangements, with everything having it’s own individual home, utterly improbable in such number and variety, and so highly organized and grouped with fitting parts everywhere.

She’d also been told that lots of scientists thought nature’s patterns came from a natural law of energy, that everything sought to maximize its power, which honestly, just made her wrinkle her forehead… She did not know, of course, but thought there was something hidden in the magic of how things in nature so often yielded to each other, an obvious secret to how things come to fit so closely. So she quietly thought perhaps that seemed at least or was perhaps even more important.

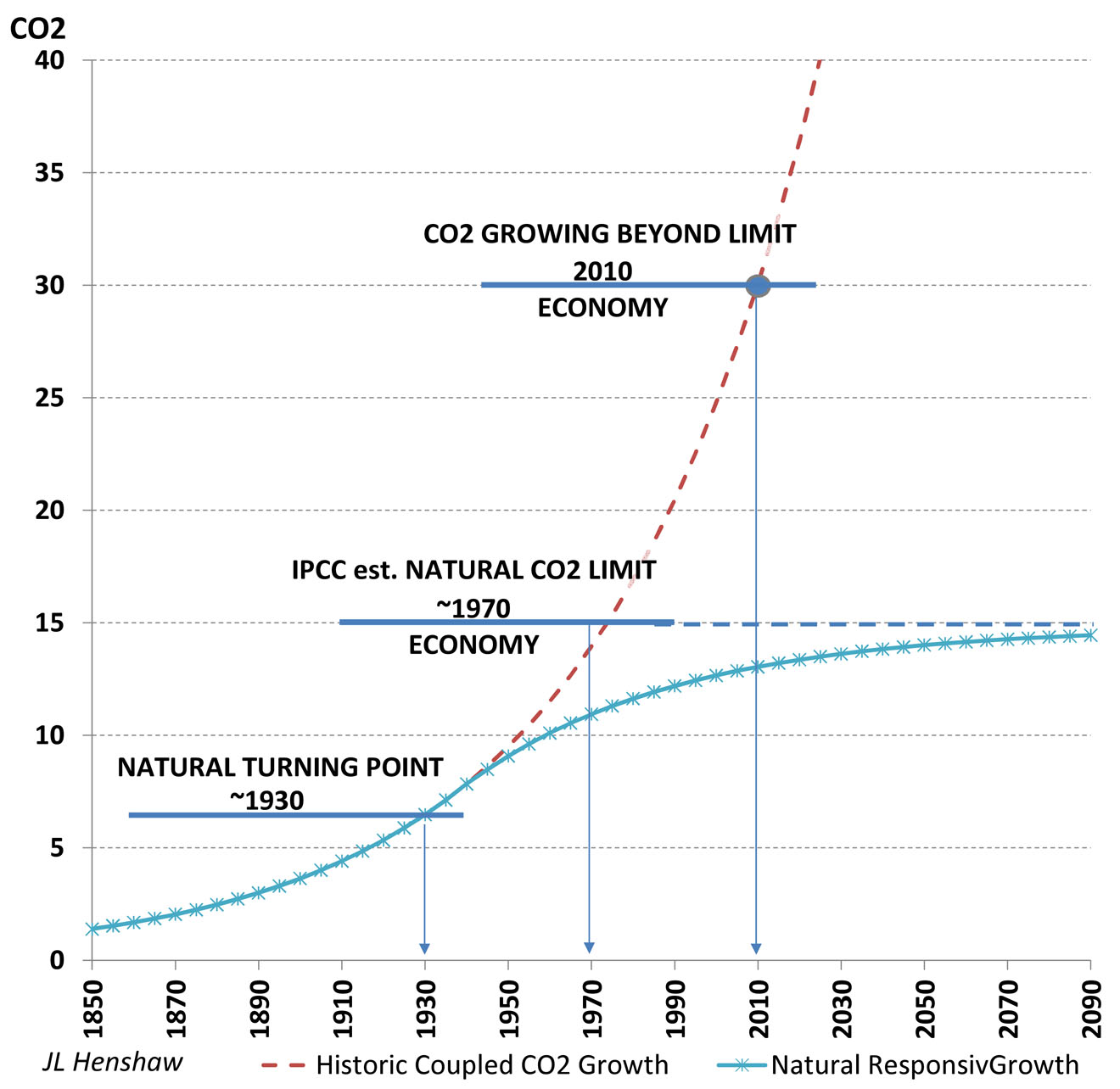

What she had planned to do that day was use her old graphic calculator from high school, to do an experiment in rewriting the history of the economy, laughing as she said it that way. Could you show an economy as being responsive, seeking to get along, rather than just getting more and more aggressive in looking for, in the end, how to get in ever bigger trouble? What would it be like, she wondered, if people could be responsive as a rule. The idea had come up in reading that the climate change scientists, the IPCC, had said we needed to reduce world CO2 production to half what it was in 2010. It was only recently in fact that the world economy had been below that, and now everyone was saying we had to go back but probably couldn’t. She felt she had all the facts, though.

So she had the idea to just…

– totally redraw the history of ever growing CO2

– to show mankind as being responsive to the approach of climate change

She didn’t get it to work till quite late that night, but it worked! What she had of course been thinking about, and felt that anyone who mattered constantly worried about behind every other subject, was the strange continual way the human society was so energetically trying to destroy its own future. The evidence could not be more clear, with the ever faster consumption of everything useful on earth, that an economy maximizing its growth unavoidably does. Anyone can plainly see that happening, as climate change keeps accelerating faster than expected. Everyone hears about the ever increasing loss of natural species from disrupting ever more natural habitats too, and the impossible debts nations have accumulated making their decision making impossible, and so many other disturbing things.

It wasn’t a “debate” to her. It also wasn’t her “cause” either. She also did not really see it as her job to change other people’s minds. It was just something she personally needed to know, about her own life, and whether it could be meaningful.

What Kepler had been mulling over, again and again, was that the natural world seemed just so very smart. Even though very few things in nature had “brains”, a great many things seemed “as responsive” as if they had brains, and humans with brains seemed totally unresponsive to such enormously important things. Microbes and insects really don’t have any way to “know what’s going on” at all, but when you see them behaving they are being quite responsive to change around them, both to changes in opportunity and to danger.

How could that be if they didn’t have some way of doing it?

She wondered if they were just being responsive to changes around them as a rule, rather than following rules imposed on them and only surviving by accident as she was being taught in ecology class? She liked the idea that everything had its chances individually, and it agreed with what she say, but nature didn’t seem to her to be relying on survival by accident at all!

However it’s done, she reasoned,

it must be incredibly simple,

If even microbes scatter when threatened, it really could ONLY be a human way of jinxing our own thinking that would keep us from seeing how. So the idea for a project was to calculate how it would affect an organism approaching danger, if it’s rule was to shy away from danger just as fast as it approached opportunity. It seems logical at least, and “part of life”. If what you are given is that nothing in live knows what’s really happening, then when you find yourself running into opportunities and hazards all the time,

your own ability to change directions

might be about the same, whatever direction you need to turn.

Somehow it just seemed obvious that most anything has to do that. Things have to slow down about as well as they speeds up, just to avoid crashing into where you’re going once you get there!

She too, of course, felt some personal “license” to explore such things, that other people might not. It just thrilled her, given her namesake’s accomplishments. But she also felt guilty, that at the end of the 16 th century, the way Johannes Kepler had seemed to find, it looked SO much easier to change the whole world than now, with our great multi generation worldwide struggles that seem to accomplish so very little.

How could it possibly be done any other way, but

somehow find a way to do it very very simply again, she asked herself?

So she set out to calculate the year when the world economy’s growing use of fossil fuels would have needed to reverse direction, in order to smoothly and comfortably respond to and stay within the natural limits of CO2 for humans and nature to have a safe climate on earth. The numbers to use were known to everyone, too, all in the news and discussed in class. It just seemed nobody was really considering the implications. To her surprise it did indeed turn out incredibly simply, that the year was 1930. She thought: “THAT would have definitely been doable.”

What she did was:

|

The picture looked like this:

As Kepler studied and studied it. It almost seemed TOO simple…

The answer appears to be: “Just respond to limits and opportunities the same way”

What it seems you’d get by responding soon enough to do it naturally, is a world with a prosperous 1970 scale economy, that isn’t broke, traumatized and in ever more desperate trouble. It’s an economy that by 2010 would have had 80 years of investing in getting better and better at running things, rather than getting in bigger and bigger trouble.

That such an obvious solution to something like the climate crisis, to have been available all along, with people already having been talking about the inevitable need since before 1900, seemed to her incredible. Major environmental protections were put in place before 1920. Back then only protecting one resource or beautiful place at a time from ever faster increasing disruptions of the economy was ever done. People seemed appeased with things like the creation of the wonderful US national park system. She had wondered about that too, though. It must have been “political” or something, somehow, as the simple math makes it all too crystal clear that protecting one thing at a time can’t possibly be enough.

The professor

So she thought and thought about it, and finally got up the courage to ask her professor, in her introductory economics class. She was really proud of her simple little project too. So she showed him her pocket calculator and the curves. He was indeed a bit startled at first, having a student that went right to the point in asking the obvious questions, that others seemed to always avoid somehow. Sometimes he liked that from his students, today it was just a bother.

So what he said was,

“Oh yea, we don’t usually talk about it that. If you must look into it, JM Keynes also made that mistake, and came up with essentially the same idea, talking about the inevitability of “roundabout” means and complication hobbling growth much like you’re saying for CO2. It’s in his main book, Chapter 16, he considers whether “this more favorable possibility comes to the rescue”. But nearly everyone else calls it “the fallacy” and ignored it, because it would mean deciding to not have money automatically multiply anymore.”

After a pause he then said,

“I don’t really know what else to tell you. Do you have anything else to ask?”

Of course Kepler was just astounded that a truly great man’s saying something clearly impossible would have to stop sometime, would then be considered “a fallacy”. There obviously was something she was completely missing. She’d learned what investment does though. It builds stuff for the future.

So she asked him,

“Well, OK, but why couldn’t you change how investment is done, so it invests in future profits rather than future disasters.”

What he said then made her run home crying, really unsure about the whole world and her life all of a sudden. Though, perhaps he would not have realizing the effect it would have on his best student,

He replied:

“Oh, no, humans could never learn to do that!”

_____________

The professor was a bit taken aback, of course, but didn’t happen to think about it again till the next day at lunch. He happened to recall that in Chapter 16 Keynes had also said he rather thought the time to reverse what investment was used for might well not be far off in the future. That idea may actually have been what people found so completely unbelievable, to call the whole need to respond to limits a fallacy. It was very interesting to him that now it was his own student, indeed, who had shown that the time for the economy to change directions, even when Keynes was writing… was already in the past.

jlh