Supplemental notes for 3/12/10 Economies that Can become part of Nature

_______

How an economy can relieve growing internal and environmental strains that would trigger a wider than local collapse.

It’s a subject enough people need to understand before the shrinking time to respond slips away.

5/18/19

Current economic thinking on Keynes “widow’s cruse” repeatedly misses the whole point. Keynes illustrated his discovery that capitalism would have natural limits of overinvestment with the parable from 1 Kings 17 about Elijah granting God’s gift to an impoverished old widow, of an inexhaustible jar of flour and jug of oil, to last until rains came again. In Chapter 16.V of The General Theory, he directly states what he meant, saying that to avert the worst crises of capitalism as growing returns from exploiting people and the earth reached limits:

“In so far as millionaires find their satisfaction in building mighty mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death, or, repenting of their sins, erect cathedrals and endow monasteries or foreign missions, the day when an abundance of capital will interfere with an abundance of output may be postponed.“

It is clear he is talking about the world economy becoming managed as a healthy cash cow, solving the “tragedy of overinvestment in the commons” by spending returns on investment. That is the better choice than letting the share of income earned by capital continue tending to infinity as the productivity of exploiting people and the earth shows diminishing marginal returns. To put it crudely, you might simplify the parable to “better to be a cash cow than dead meat.” Better a circular money economy, as in naturally balanced systems, than endless compounding of worthless promises.

For the owners of the world the choice is to either be generous enough in spending their profits to relieve the people and environment of ultimately unproductive demands – caring for the earth, or alternately to drive their exploitation to exhaustion, leading the earth into an all-consuming plague of plagues as growing ealth extraction becomes more disruptive than constructive. In Chapter 16 Keynes also said that time we would face that would not be far off, and now it appears we see he was right.

Historically the Romans and the fabled “Egyptians” of the Exodus seem to provide the real world models for owners of the world, making the wrong choice as their fortunes reached natural limits. The actual Egyptians, thriving for ages giving good work to their population during the annual floods, seem to offer one example of the other choice. Nearly all of us make that basic choice in our careers, learning to back off from making excessive demands on our environments as a key investment strategy to use, letting other things flourish, all the time.

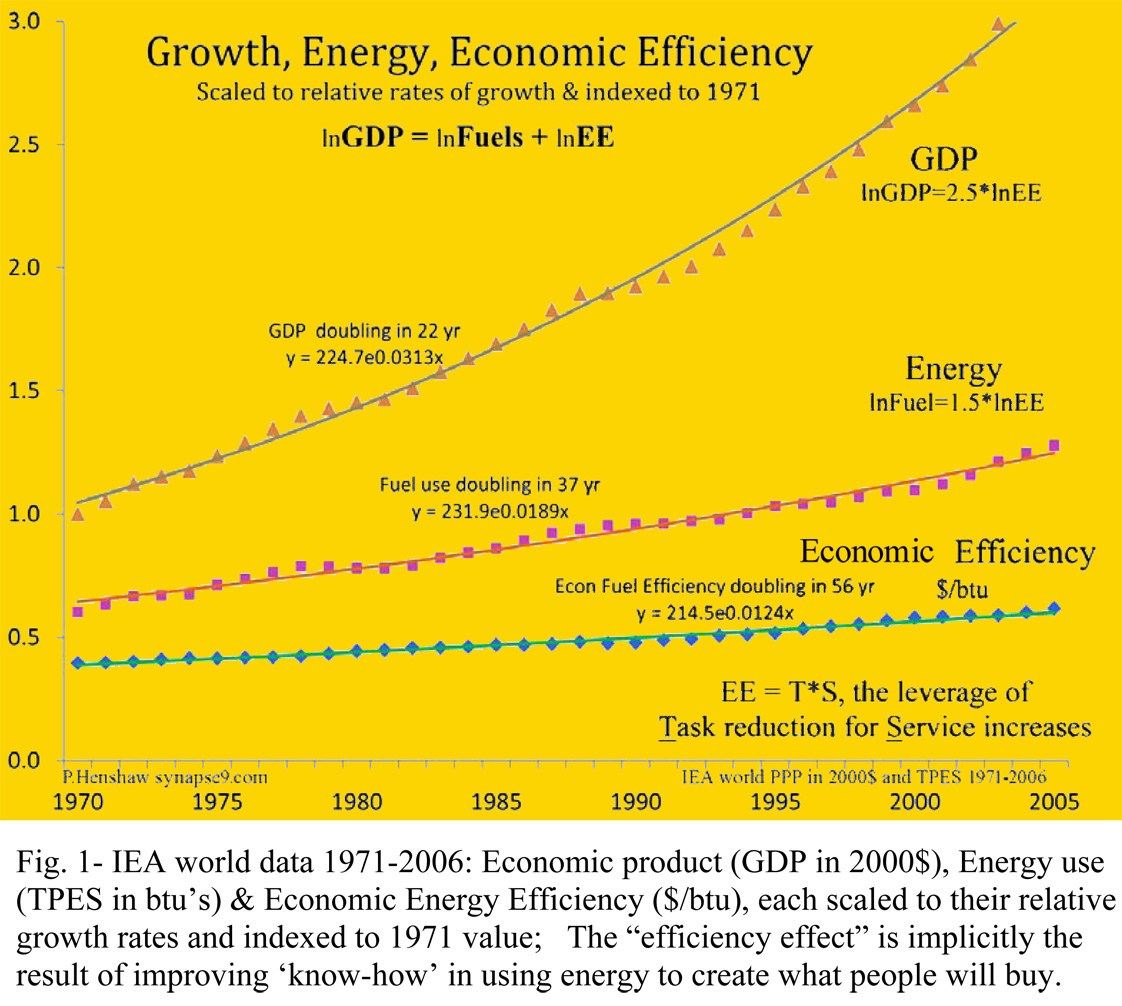

Of course, there are lots of other principles to follow in maintaining the productivity of a network of resources, such as not spending all the profits on unproductive services. Equally tough moral choices lie in needing not to accumulate overhead that depletes your energy returns on energy invested, EROI. It would seem very easy to bankrupt a big and otherwise seemingly healthy business, culture, or whole economy, letting its energy costs rise to equal its energy returns.

6/15/11

J.M. Keynes devoted the concluding theory chapter of his design for modern economics, Chapter 16 of The General Theory, to describing the natural limits of money in a free market system .

It seems economists were generally confused as to why Keynes would consider that, and didn’t study what Keynes had to say about where following the rest of his theory would lead. He pointed to why a market economy will continue to have growing savings and keep making growing investments even when natural limits and environmental conflicts make that increasingly unprofitable for the system as a whole.

He also described the alternative that would allow the whole system to remain profitable in the long term. Either way the expansion of wealth and money would reach a climax. Either investors would continuing to accumulate savings until they produced no net returns and businesses failed, or by spending enough assure the long term profitability of the whole.

The one choice is utterly disastrous and the other a bit unappealing to some but a way out of a real trap. It’s counter intuitive in many ways, and forces us to recognize that every part of an economic system depends on the good health of the whole. Continue reading Keynes’ “widow’s cruse” – capitalism to natural growth