Leland, Thanks for forwarding Christine Harper’s (Bloomberg Jan 31) notes on “The lonliest man in Davos…” reporting from the meeting of the World Economic Forum.

It all sounds like the very same script pulled from the drawer at every stage of history, as the next greater ecological or financial bubble emerges,

people running about madly trying to patch the weak points in the containment,

…hoping against hope that each greater failure isn’t leading to the inevitable for financial systems designed to ‘stabilize’ growing expectations for results from physical systems not providing them.

When I first noticed that problem long ago I quickly narrowed it down to that deep error of intent, and then to how our accounting system keeps records of it on the faint hope that the impossible will someday be fulfilled. It treats the physical world as a “black box” of unknowns, relied on to multiply returns that can’t be confirmed or contested. So I say, why not “look in the box”, see what you really have!

If so many people see an ‘Incipient Sovereign Crisis’ approaching, realizing that forestalling the next bigger crisis as it approached didn’t work so frequently before can turn our attention to the standard solutions that regularly failed , like “increasing reserve requirements”.

That can only work if there is sound value in what you put in reserve, and the cascades of claims against it are limited in scale. Both assumptions fail in our case, since what we’re trying to stabilize is a system of maintaining ever growing promises for the productivity of accelerating the economy’s use of natural resources, now resisting our efforts in new way.

All money is based on promises, whatever the currency, so what we end up putting in reserve may be trusted information at one time and trusted misinformation at another. How the natural world responds to investment naturally goes from ever more to ever less profitable as resources are depleted.

At the point of crisis the reserves are then naturally inadequate to quell the cascades of failure coming. So I’m not certain of Wilkinson’s details, but I certainly agree with his general conclusion.

The fault does not seem to be the currency being used, but the use of currency of any kind to record commitments to produce ever multiplying returns. Every time in history people have seen the failure of that coming, and discussed it at a meeting like the one at Davos, it’s been apparent that the producing economies were falling ever further behind on their obligation for multiplying payments, for natural causes.

Then people decided “the system is too big to fail” (to be allowed to stop multiply expectations not being fulfilled) and committed themselves to it ever more deeply. So the problem is with perception, and the question one of how to fix it when everyone seems to agree what is needed is a better false strategy. In that situation it becomes satisfying to think that maybe we could just throw ALL our good money after bad, after losing the first half.

The “data” seems to suggest that part of what keeps people attached to false thinking about a dire situation is the dire consequence itself, that just keeps them frozen in their thinking. Even if they see clearly that just forestalling the next bigger crisis won’t work they cling to their failing model by having their imagination of alternatives blocked.

What blocks their imagination is the information model they once trusted and relied on successfully itself. The crux of the problem is that why the information model is no longer working is *not in the model*! So they cling to it ever more not knowing what to do.

Something’s not right when we all know that “Debt = Credit”, and our world is at a point of owing itself so much money it will need to stop work. What I’m suggesting is that if you can’t use an information model to ask how it fits the world it’s in, well it’s not much good.

Then even if you can’t find a way to test a failing model, that fact can give you a release from its structure and an invitation to become curious about what’s happening around it. We should clearly not need to shut down the world just because we’re coming to a point of owing ourselves too much money.

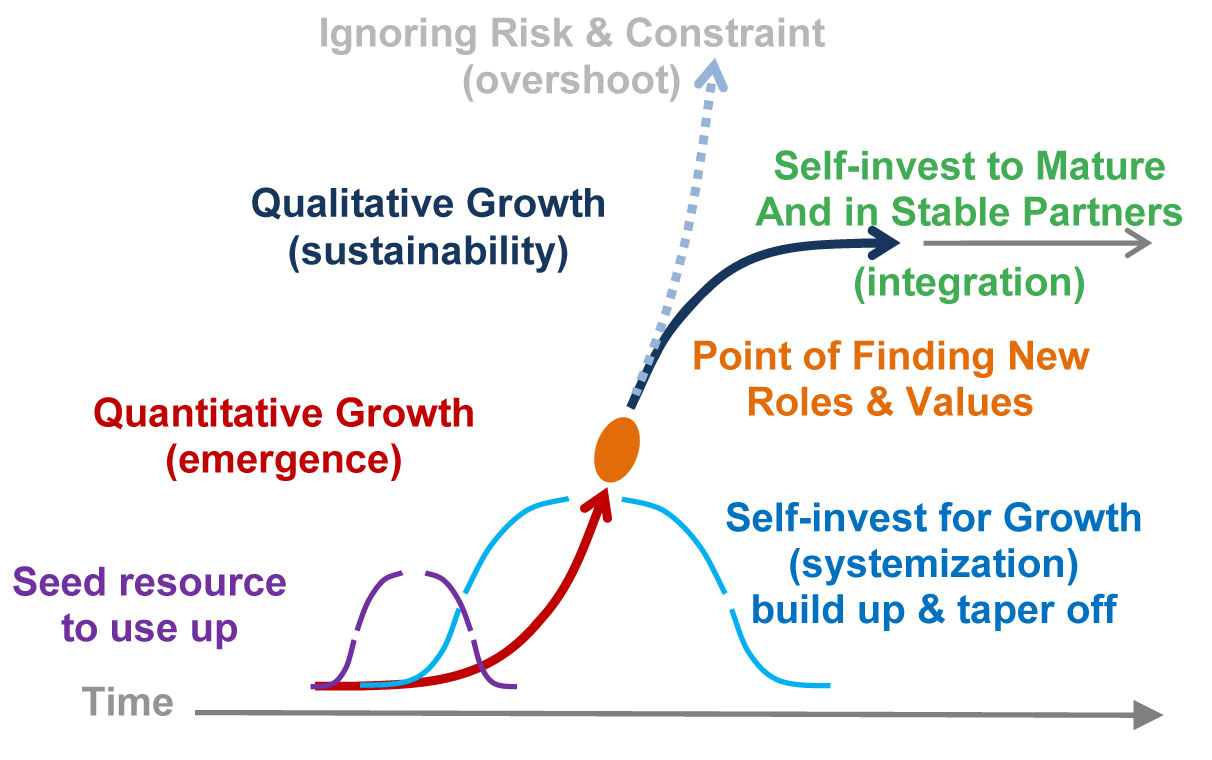

Growth systems that come into ecological balance with each other are exceedingly common in nature, maintaining marginal frictions allowed by far greater mutual benefits. They also begin their existence with a close approximation to the “creative destruction” principle of economics, multiplying their own scale and control of their environments, while repeatedly disposing of their own roots as they develop.

To keep “creative destruction” profitable, however, they somehow sense that ever growing conflict will become unprofitable, and so not a good thing to take to the end. They do it so very smoothly it goes quite unnoticed most of the time is part of the catch.

Nature makes it look simple. So even if it might be quite difficult, that’s proof it’s not impossible. It looks as if maintaining the creativity of systems at their limits of growth is only a matter of reorienting the investment strategy, toward using profits for developing ways of avoiding rather than overcoming conflict.

Growth leads to a new identity, then finding a path

Growth leads to a new identity, then finding a path

to discovering its new roles.