Posts on the UN NGO Week 4 Sustainability dialog for “WorldWeWant2015“ – Post II references Post I below it, and is in reply to Alison Doig, working with Christian Aid, Green Alliance, WWF, Greenpeace and RSPB to understand the nature of the relation between environmental sustainability, quoted at the bottom. Alison lays out a set of simple but broad principles for sustainability, a preview of a longer paper, but missing key issues for working with the natural phases of developmental processes for environmental transformations. jlh

See also Jan 2014 OWG7 proposed World SDG incorporating this principle and others

__________________

Post II Jessie Henshaw Fri, Mar 1, 2013 at 1:00 pm

Alison, Your approach seems quite sensible, but to be missing one of the key controlling variables for all these objectives. That’s whether the improvements you seek are “by an accumulation of larger steps” or “by an accumulation of smaller steps”. An accumulation of smaller steps is probably sustainable, and an accumulation of larger steps is necessary to get any process of change started, but quite unsustainable, is the interesting rub.

This distinction is also quite missing from the whole discussion, always has been actually, so you’re not to be faulted for overlooking it. Still, it does in fact control whether any of the things we hope will be sustainable actually will be. I’m a systems physicist and this is the subject I study, both how all sorts of development processes need to begin and end, and how easy it is for people to overlook the whole subject. I’d very much like to work with you if you see how to build any of this into your report in progress.

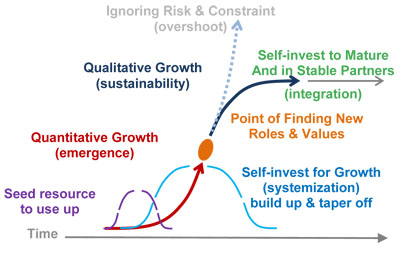

As a matter of change over time, start-up development always needs to be divergent and expansive, a series of ever bigger steps, and maturing development always needs to be converging and self-limited, a series of ever smaller steps. In-between the physical momentum of change builds and decays.

For the “three dimensions of sustainability”, social, economic, and environmental, it applies to all three.

To start any social, economic or environmental transformation an effort needs to start small and grow, then converge on the desired end (for the physical continuity of the process to be maintained, what I study)

start with small steps that get bigger

and

end with those larger steps getting smaller

The above conceptual graph of development over time, shows that natural succession of change as an aid for thinking about the changes needed to understand developmental changes in environmental systems generally. Sustainable growth generally starts off as just a desire for change with no clear end, taking ever bigger steps, and then changes to converge on some sustainable objective once that is discovered.

Missing from the general discussion of the “three dimensions of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental” are both a) how change of any one type gets started, and then b) how change of any one type gets completed. We’re discussing them sometimes, but not in any systematic way, and leaving critical things out.

It’s less easy to define these natural phases for social change or environmental change though they’re generally recognizable from a broad perspective. For economic change, though, the math is elementary.

For sustainable economic transformations to take place you need a period of multiplying profits followed by a period of converging on producing steady profits, a hard and fast definition of physical “sustainability”.

The same principle, starting with multiplying profits then converging on steady profits, would apply to either social or environmental transformations too… if you could define and measure what you mean by “profits”. It’s just a lot easier to do that talking about money. So I’d like to help you or others begin to incorporate into your definitions these natural phases of development needed for the physical continuity of change (the physics part of it) for successful transformations of environmental systems to be sustainable.

You may see already that while social and environmental transformations have difficulty getting started they then generally have little difficulty converging on a sustainable end. Economic transformations in our world are also difficult to get started, but are then expected to participate in an unending succession of ever bigger steps of change, that never stabilizes.

For economic transformations to be sustainable, however, it’s actually physiologically necessary to have converging growth follow the diverging kind, and learn to use the kinds of “scientific measures of the total effect” such as I described before (Post I below), to indicate whether you are or not.

– See more at: http://www.worldwewant2015.org/node/312705?page=1#comment-48199

Post I Jessie Henshaw Fri, Mar 1, 2013 at 4:00 am

A surprising omission from sustainability plans generally is the use of scientific measures of the total effect, that would indicate the degree of change in sustainability for the environment that results from attempts to reduce our impacts. We tend not to see any measures of total impacts on the earth, or net changes, in evaluations of sustainability efforts such as in CSR reports. Why the direct measure of sustainability is neglected is it takes a little rudimentary systems thinking.

The science of how to do it takes being careful to use only reliable measures, so only possible for limited things, but the information can also be quite valuable. For example, many types of “sustainable development”, considered for regional development effects, turn out to still expand the regional economy, and so add to the total urban infrastructure and downstream demands for energy and other resources regionally and globally.

This is actually the worst kind of “backfire” effect of sustainability plans, increasing our economic addiction to growing resource consumption. So it is particularly surprising these measures are so little studied.

The key to the scientific method that makes these measures possible is understanding that when people spend money it inevitably goes to paying for “average human consumption”.

Only people take money in payment for what they do. Neither nature or technology take a penny, so ever dollar paid for resources or for machines or their products it all actually goes to people for their consumption anyway!

When money is paid for anything it gets split up between numerous businesses and their numerous human recipients along the supply and service chains that deliver any product. That causes the end user recipients to be extremely numerous and widely distributed, and so turns out to be for human consumption that is “about average” per dollar. That’s an available simple ratio of IEA statistics. Systems Energy Assessment (SEA).

That curiously simple way to measure the impact of money provides a surprisingly accurate way to measure and compare the scale of world impacts of economic choices. They’re proportional to the end user consumption generated. So it gives you standard measures of a business’s, or a whole community’s, real share of the economy’s total, allowing comparisons of change from before to after implementing any kind of investment choice.

It can also be improved in accuracy, taking more effort to study the details of individually traceable impacts. That further assessment may show a particular sustainability effort has impacts that are above or below the average, something no other method will actually tell you. The realization that money actually pays only for average consumption, directly, is the conceptual hurdle that seems to have prevented this quite useful hard measure of sustainability impact from being widely studied, improved on, and adopted.

The three most important discoveries you make are that:

- Our share of the world’s total impacts on the earth is actually proportional to the end user consumption our efforts result in,

- Our share of world’s end user consumption is proportional to the income a development generates, and doesn’t decline in proportion to the efficiency of the business, but only in proportion to the efficiency of the whole economy.

- and … The historic rates of improving efficiency for the whole economy are much slower than its historic rate of growth.

The takeaway is that “sustainability” efforts that ignore these measures tend to be unaware of their total effects, and very probably have growing negative impacts for being development efforts that naturally distribute their earnings widely and contribute to the expansion of the economy as a whole.

Incidentally, it also shows the important practical value of learning how to take whole system effects into account.

– See more at: http://www.worldwewant2015.org/comment/reply/312705#sthash.kKZRbHGA.dpuf

___________

Alison Doig Mon, February 25, 2013 at 10.50 am

The international development NGO Christian Aid has been working with Green Alliance, WWF Greenpeace and RSPB to understand the nature of the relation between environmental sustainability and the post-2015 development framework. We will publish our paper in full on this in mid-March, but a summary of conclusions are below.

Future proofing: environmental resilience tests for post-2015

Only through truly resilient development that considers our changing environment and the limits to our resources will it be possible to tackle the root causes of poverty and inequality in the long term, ensuring poverty eradication for current and future generations. The post-2015 development framework provides an opportunity to ensure that all countries are set on a development path that guarantees a sustainable future for all.

Climate change and related disasters present huge risks to sustainable development and poverty eradication, especially for the world’s poorest, many of whom are dependent on the natural environment for their survival. While progress has been made since the Millennium Development Goals were agreed, in many countries economic growth has not been inclusive or equitable, failing to eradicate poverty and undermining the natural environment.

Any newly agreed goals must now take a different, more resilient path: one which makes all nations better prepared to manage risks, enables them to eradicate poverty, makes them more resource efficient and secure, reduces their dependence on outside help, and makes the best use of money for development investments.

To achieve this outcome the post-2015 framework needs to addressfour environmental resilience tests:

- 1. Support environmentally resilient poverty reduction, by building national and community capacity to respond to climate impacts and natural resource constraints. For example, by:

- adapting water, energy and food systems to respond to a changing climate and other resource constraints;

- supporting small scale farming to increase flexibility and diversity of production, as well as delivering local food security;

- identifying and tackling underlying risk factors for development, such as rapid unplanned urbanisation or decline in ecosystem services and biodiversity

- 2. Deliver resource efficiency and security, by building good resource management and sustainable resource use into national growth models, as well as increased transparency, access and rights for local communities. For example, by:

- seeking international shifts in resource consumption to more sustainable models, ensuring a more equitable and secure supply for all;

- requiring clear reporting from the private sector, which encourages positive environmental and social outcomes, drives good practice, and reduces negative impacts on people and the environment

- 3. Enable access to sustainable, secure, clean energy for all, through economic growth models built on low carbon, renewable energy sources and energy efficiency. For example, by:

- encouraging developing countries to ‘leapfrog’ to renewable energy, to deliver sustainable energy access and green and equitable economic growth;

- using decentralised energy systems to deliver renewable energy to communities, clinics, schools and businesses

- 4. Reduce vulnerability to and the impact of disasters, and in turn reduce the need for humanitarian aid, while protecting lives, livelihoods and economic investments. For example, by:

- creating partnerships for disaster risk reduction (DRR), including climate scientists working with local authorities and communities to develop disaster response systems;

- building DRR measures into infrastructure and services, such as establishing national cross-sector DRR platforms to work between agriculture, business, health, education and others.

This holistic post-2015 framework must apply to both developed and developing countries, enabling all nations to live within the planetary and social boundaries which are essential to long term global sustainability.

– See more at: http://www.worldwewant2015.org/node/312705?page=1#comment-48199