We need humility to live with a world that works mostly by missing information.

Responding to John McCreery’s recent comment on Open Anthropology – Arguing From Limits (also quoted below mine here) discussing the hazard of raising doubt about people’s faith in using efficiency to reduce environmental impacts, as I had called it “a mirage”. The problem is that the visible energy uses people focus attention on are much smaller that the hidden ones we act as if quite unaware of. For the full exchange you You might start from my first comment in reply to John.

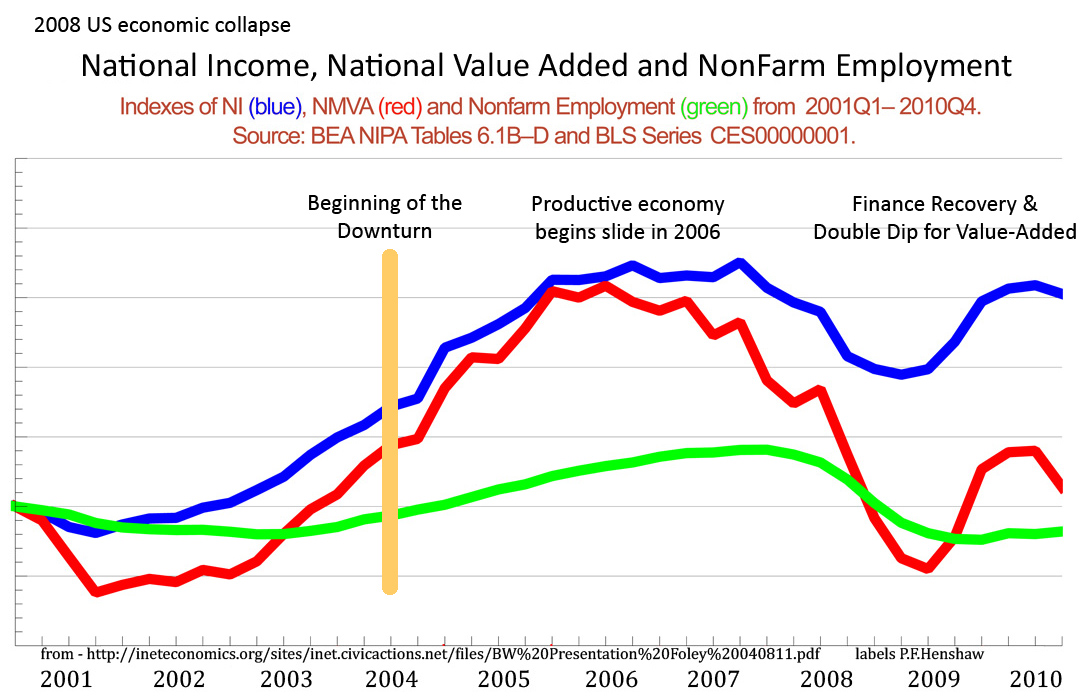

The scientific evidence (from Systems Energy Assessment) is that the visible energy demands of technology that people focus on are nominally 20% of the total, and the hidden energy demands of the commerce that uses technology is nominally 80%. That makes the effort to reduce energy use with technology efficiency, while expanding commerce to make money, quite self-defeating as a way to reduce energy use. This seems to be one of the more direct ways to explain the problem.

_________

John, There is certainly a moral quandary, if taking away a hopeful but mistaken belief causes people to give up and quit! That’s the kind of dilemma that get’s worse if you don’t acknowledge and find the right response to. To me that also involves looking at the apparent “easy” solutions, and asking if they really solve the right thing or not.

You might assume you’re talking to one part of an audience and really needing to shift attention to another. That “worst case” example is indeed one I’ve repeatedly run into.

I’ve also found that no amount of “icing” on the cake changed the flavor of the message those people were getting. To me it says I needed to find other people or other ways to address the greater faith and intelligence that everyone sometimes displays, that people yearn to have more respect for.

I may not know quite how to say it, but I think a society needs to be led by people who would see the problem as “career change” rather than “emergencies”, a need for more truthful and communicative models. If the “mirage of efficiency” is caused by people believing that it’s the energy uses they see that control events, when in fact it’s the energy uses they don’t see, the error is a kind of arrogance of information.

Our information is then serving to blind us to what we might well have understood anyway, from how money works. So to develop a “new career” as conscious beings, and be more alert to what’s missing from our information, would involve watching for what some story teller may be hiding from us with it.

It’s great that you suggest Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings fable as a model to discuss this from. I ask whether the fable leads the protagonist to a more practical or a more fatalistic view of life in the end.

Sure, striving for the truth is arduous and dangerous, but don’t all those great selling books and movies on the “heroic journey” theme seem to end in “the great truth” being a magic spell? That might not always be false, but is at least false for the successes your efforts are responsible for earning. It may well feel like “pure magic” when you see the skeleton walls of your new house capped by a roof for the first time, giving you your first glimpse of the end product. It’s not magic that got you there, though, and not magic that’s needed for the career change in our mental habits for people to learn to look beyond their information to understand the realities of the natural world.

How people change how they think seems to be by learning experiences with their feelings passing new questions to their reasoning, and reasoning passing back new propositions to feel the meaning of, and then sleeping on it and mulling things over with friends, as a way of exploring. A lot of what I don’t know is what ideas will awaken that kind of curiosity and hunger for learning in other people.

Looking for it, though, is much of why I try to use the vernacular, and associate common experiences with uncommon points of view that came from a more scientific curiosity. The idea of calling our cultural faith in efficiency “a mirage” came from John Fullerton as his way of condensing some of my scientific models.

I think that image does just what is needed, as far as connecting reasoning and feeling on the subject. It still needs to be handled in an emotionally supportive way for people who have not really considered it yet. So, that’s a model, connecting reason and feeling for new challenges, and giving people emotional support as they struggle with them.

In that article of mine on “A decisive moment for Investing in Sustainability” I try to combine raising the challenge of new kinds of learning with the emotional support people need to make it their own. The subject there is our belated discovery of our emerging global resource crisis, with demand now exceeding supply systemically and world markets responding by raising prices in a panic.

For sustainability professionals being called in “to fix the problem” and needing to invent new models at the same time, demands more from them in wits and courage than anyone can ask of them. Because this crisis is now upon us, it’s also just too late to “hurry up” to avoid it. The question seems more one of choosing to fully engage in learning how our world is changing and making that a new part of our lives.

_________

Responding John McCreery’s comment on the thread “Arguing from The Limits”

The problem with presenting efficiency as a mirage is that the result may not be the one you anticipate. If the dream of a simpler, more sustainable life comes to be seen as fundamentally fallacious, you may well have more people simply giving up, going fatalistic, leaving it up to God, or choosing “eat, drink and be merry, for the end is nigh.”

A better approach might begin with praise for personal steps toward a simpler, less energy-intensive life (people like being flattered), followed by the observation that, in large part, we have simply shifted the energy burden somewhere else, where the monster grows stronger until it is ready to devour us. We have won a battle, but it’s only a skirmish.

The war will be long and hard. Instead of pissing on the buds of what could become a major change in attitude, treat them as heroic first steps in the long march to the ultimate goal. Consider the narrative arc in The Lord of the Rings. If Tolkien had introduced the Hobbits as a bunch of deluded idiots, who would care if Frodo managed to destroy the ring.

Also, thinking about what’s going on now in Japan, a catastrophe might help. With the horrible news from Northeast Japan still fresh in everyone’s mind and emotions, the Fukushima reactors offline, and a lot of the power grid still in a mess, people here have reacted positively to government calls to save electricity.

Train schedules have been reduced, half the escalators are stopped, stores are closing early, and the neon has been turned off all over town. The government has announced a policy under which industry will be required to lower power consumption by 25%. The last time this happened, during the 1973 oil shock, Japan became the most energy-efficient country on the planet.

I recall a conversation with a friend. We agreed that planning to avoid catastrophe is important. That said, the really critical issue may be whether we are prepared to respond effectively when catastrophe strikes. I was reminded of one of Robert Parker’s Spencer novels, whose protagonist is a hardboiled Boston detective.

In this particular tale, Spencer has rescued a kid whose parents are threatened by the mob and is driving him up to a cabin in Maine, where Spencer and the kid will hide out and keep the kid safe from becoming a hostage. The kid asks Spencer if he’s worried that the mob might track them to the cabin.

Spencer replies that he doesn’t worry about that. All he thinks about is how he will respond if they do. As ugly and manipulative as it may sound, I wonder if the same principle doesn’t apply to what you are trying to do.

By all means keep plugging away and spreading the word about the problem you have identified. But think seriously about how to turn the next, inevitable catastrophe into a springboard for getting the message out to people who are briefly more likely to accept and move on it.