What’s the cost of increasing investment when you’re already over-invested…??

Many organic and environmental systems display talents for taking care of themselves we could use, using internal steering to avoid approaching hazards and be responsive to change. In studying how they do it one comes across some wonderful new lines f practical of environmental systems research.

fyi – originally posted to World Ecology Research, a related recent post here is Where I’ve gotten so far

Natural systems display remarkable feats of self-control, but studying them fail to connect with the current scientific paradigm for representing everything as controlled by external forces, described by equations. The internal steering mechanisms within natural systems, organisms and economies, etc, are continually reorganizing in much too fluid ways to be described by any kind of equation, or rules for collections of automatic agents either.

The continued interest of the sciences remains only entirely about control theory, unfortunately.The lack of interest within science hasn’t stopped people from productively exploring the territory, only prevented communicating with our wider intellectual culture.

If you look at recent scientific history there were a number of scientists who made great contributions to understanding natural systems, whose work on other questions was accepted while their insights into considering complex systems more like organisms was discarded. It’s not hidden from view at all, for example, that nature arranges environmental systems is as cells of organization.

Those cells of organization also clearly emerge from their own environments, by a self-animated complex process of growth. One needs only ask whether that organization is delivered from the outside or generated within, to observe that complex systems seem to grow by exploiting their environments not being controlled by them. Their organization develops internally.

So, my view that our intellectual culture now finds itself a simply huge stack of “overdue homework”. Just how extremely overdue that homework is may make it seem like nearly starting over, with the whole project of learning about the earth.

For the past several centuries we have been making ever greater strides by multiplying our control of everything on earth, only now to find the process itself going out of control … Considered as a whole system, our profits from controlling nature were constantly allocated by the capital markets to multiply our control of nature, taking it too far to now to gracefully recover from.

What we need are the secrets of nature, how her growth systems come to a climax of vitality rather than of exhaustion. Oddly the first person to notice the elementally simple investment allocation strategy for doing that was J.M. Keynes.

He actually wrote the whole concluding chapter of his theory of economic growth on the subject of its limits. It’s still the correct basic template for how our economic system could exhibit self-control in managing its own growth.

Tragically to the readers of The General Theory the idea appears to have seemed completely alien, and that is why it was entirely ignored as people used the rest of Keynes’ work to build a profoundly unsustainable growth system. As an ecosystem, the strategic use of your profits to multiply your process needs to stop sometime, just to preserve the profitability of the system, whether measured in net-energy terms or a proxy measure of value like money.

When the scale of a system is stabilized while it is still profitable, those profits then become available for the self-management task of steering the system that growth built.

In 2011, of course, there is no discussion of whether Keynes’s strategy for saving the growth system from itself would be needed now, or ever, and how much it would be worth to the world economy to survive as both a cultural institution and a physical system. In 2011, 80 years later, it clearly still seems to be such a “shocking new idea” that people perennially just turn their attention to other popular subjects to avoid it.

Of course, those more popular subjects are not relevant, in the case the system is not steered to survive physically as well.

Keynes discussion in Chapter 16 of The General Theory, was on the natural limits of money. He presented it as a choice for people accumulating savings in a profitable economy until either they a) choose to stop accumulating savings and use the profits for something else of value or b) have to stop accumulating savings in an economy that generates no profits.

Saving financial earnings for more investment as a rule would only stop when aggregate investment earning become zero. Keynes thought it would be fairly easy to have increasing investment become increasingly unprofitable, as of course, we now see with riveting clarity in our present conflict ridden environment, saying:

If I am right in supposing it to be comparatively easy to make capital-goods so abundant that the marginal efficiency of capital is zero, this may be the most sensible way of gradually getting rid of many of the objectionable features of capitalism. Ch 16, iv, pp3

The easy mistake is to confuse his “marginal efficiency of capital” (a measure of the system as a whole) with being a measure of market rates of return. The total of individual rates of return can be zero when the gains of some are canceled out by the losses of others, and measures only reflecting current rates and not enduring rates are misleading as well.

By not even looking for when increasing investment would become decreasingly beneficial, economists appear to have never seriously tried to devise a way to measure whether new investment was making the economy more or less profitable in the long run. There was no need, with perpetual growing profit assumed instead.

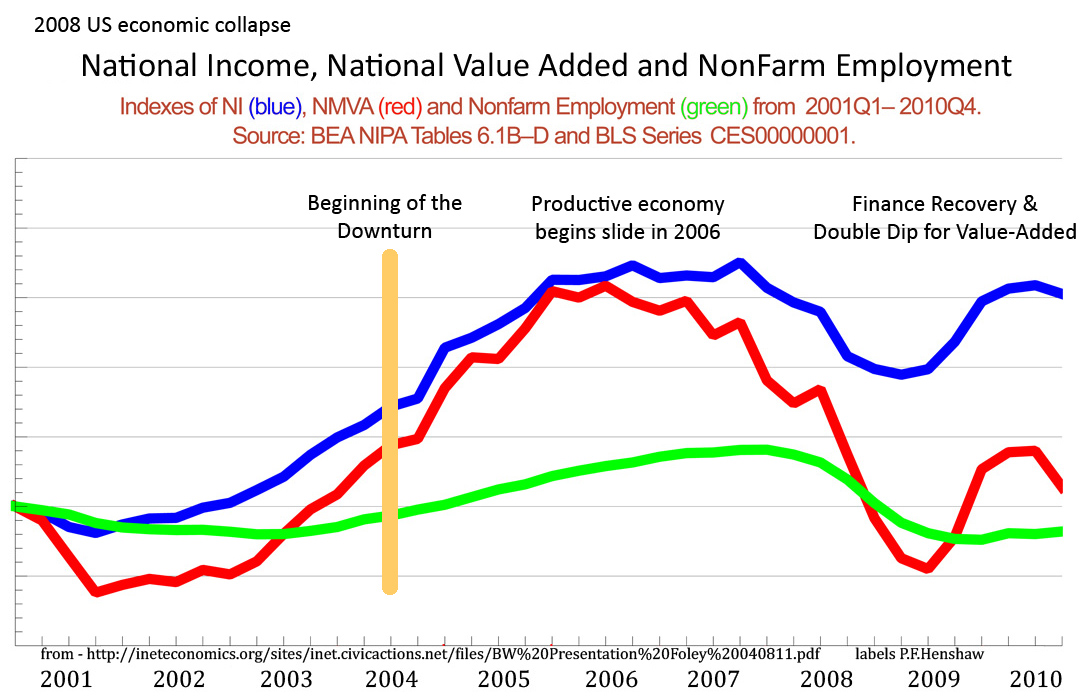

That then becomes the direct cause for economic policy ignoring the crossing point, where erupting financial liabilities went unmeasured and the net life-cycle return on increasing investment went below zero. Because we had not been asking we didn’t learn how to measure, the profitability of the system as a whole.

So Keynes’ strategy is simply and purely to keep the economic system profitable, to avoid effects of compound growth becoming unprofitable. I’ve done some of the key work on the physics of environmental systems that will enable that work, on how to make whole system measures.

That’s a study called Systems Energy Assessment (SEA)which shows from a whole environmental systems point of view how to combine “in-house” energy uses with “out-sourced” ones. The statistical finding is that (nominally) 80% of the total energy uses purchased as an operating cost of business are going uncounted. That will help to more accurately measure the real costs of business decisions both today and for the future.

The basic equation of whole system profitability, used to signal the approach of over-investment, can start as simply defining GDP as a “net” quantity, of positive and negative values. The negative GDP values would reflect the foreseeable emerging liabilities of unsustainable development in the past, for example.

That might also be thought of as a negative discount rate, as costs not only for mitigation, but for also having to prematurely rebuild the infrastructure of the economy if over expansion has made it unprofitable.

netGDP = GDP + negGDP

as an environmental measure depreciation due to over-investment in the earth.

One clearly needs to start by carefully choosing only firmly answerable parts of the question to ask, rather than just guessing at totals. You’d want to combine hard measures of clear financial costs with proxy measures to watch carefully, in attempting to make netGDP a true measure of the long term health of the system and the wisdom of its investment choices.

What happens in natural systems is that during initial growth netGDP > GDP as growth fosters growth. After the turning point (where “getting bigger” = “getting too big”) then netGDP< GDP.

One of the proxy measures that would seem most helpful, then, is to locate that turning point when the net benefit of expansion and the net liability of emerging conflicts could be seen clearly approaching. That’s the point when the natural role of finance is to switch from “growing the system” to “steering the system”, a whole new plan for the use of wealth.

The main cost everyone can understand is climate change. Our hidden financial liability for fossil fuel development is needing to basically redevelop the whole world economy.

As a round number we need to get rid of 80-90% of our carbon fuel use, in 30 years. All our development is still carbon intensive, though. There are greatly added liabilities, then, for still becoming further dependent on increasing fossil fuel use, as all the world’s growth strategies are relying on.

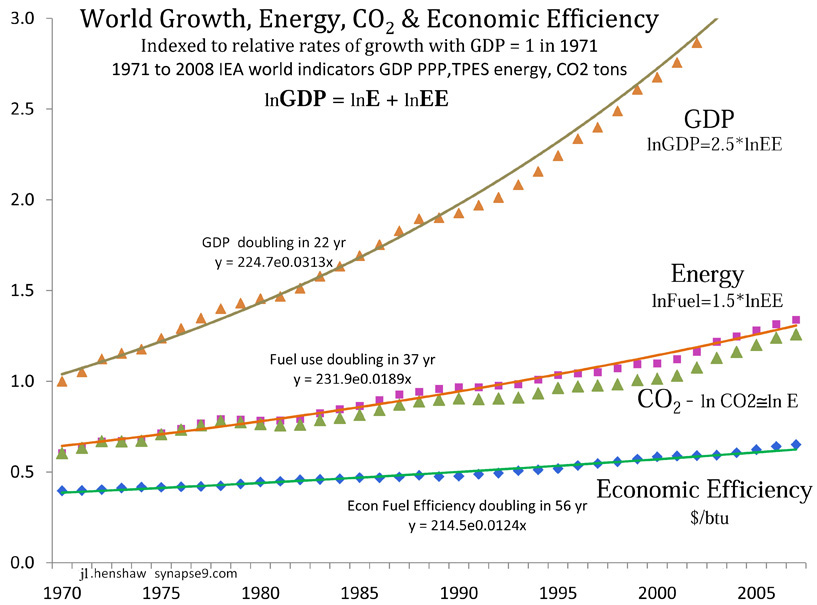

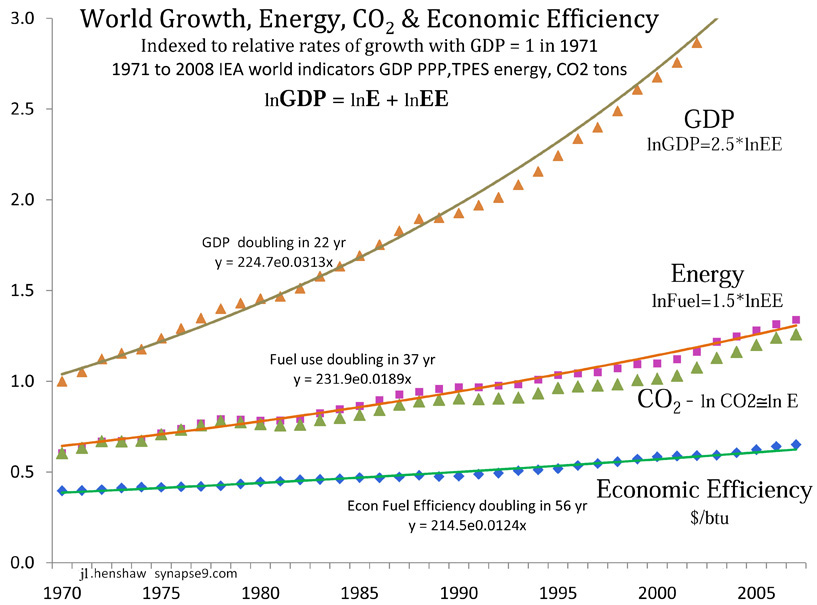

One need not have a theory to clearly see how difficult it is to reduce the carbon intensity of GDP. It’s had a remarkably slow and steady historical rate of decline, at about 1.3% per year.

So, the only apparent technically feasible way to do it is to lower GDP. Using Keynes’ template, that would done by creditors spending their savings to facilitate that without causing cascading failures in the interests of long term profitability, despite a current loss.

So yes, it’s a big problem, and people are emotionally inclined to do anything but just buckle down and ask the right questions. Somebody needs to, though, so that anyone can have a believable road map for making their decisions in the future.

We just don’t have any believable road map in public discussion now. We definitely don’t want to shrink carbon pollution by reducing living space and everything else, by 80%, for everyone to essentially share our homes and live with households with 5 times as many people.

That IS the math though. Could we find some sort of equivalent and make the transition profitably? Not in annual terms, but certainly, if we’re asking true netGDP with a view to the future.

As a culture we allowed the assumption that continued growth would always produce current multiplying profits, and we constantly discredited the people from Malthus to the present who pointed out the obvious grand error in that. To now “find yourself in the real world” we need to “study like hell” rather than keep playing games, and the way to make a profit today.