Bill Rees asked some excellent questions about my submission to the Long Term Capitalism Challenge to use natural principles for managing growth to sustain the profitability of our economic system. I think I made good responses too.

_________

Hi Jessie –

Thanks for the opportunity to review your proposal.

I agree with your diagnosis of our economic malady but admit to struggling a bit with the remedy. Let me start with this sentence:

“When people spend their financial profits on good works it also [reduces the growth of money], with the added advantage when spent as for endowments instead of to compound profits, of doing a lot of good.”

Now, at the limits to material growth, the goal of policy should be to reduce the throughput of energy and materials to biophysically sustainable limits. So the above passage raises two questions. First, what do you mean by ‘good works’? and second, would the redirection of profits from investment in productive capital to ‘good works’ reduce total throughput?

/When financial earnings are not compounded to multiply investment, and the returns are not added to savings, it stops the automatic compound growth of investments. I’m using “investment” more broadly than usual, to make my statements inclusive, to include all ways in which money is spent with the intent of having it return profits. I then break spending and investing in components if I want to study the details, using a “figure 8” model. That’s a way to construct a global model of how income is allocated and returned as income, as a closed system with regulated money supply (Concept$).

/So, “spending” then means the opposite of investment, as money spent without an expectation of return, i.e. final consumption. Then “good works” most generally means final consumption used to maintain the profitability of the economy, as a universal good and necessity for survival. One thing that economists would recommend, it think, if the added spending seemed to increase aggregate demand, is to make sure enough of it was used for non-consumption expenses like to retire debt. The intent is to have investors treat their financial investments as endowments, and think of themselves as fiduciaries for the earth in general, to keep it profitable and using their money as the world is best served.

/Spending financial returns would reduce total throughput if it kept the funds available for expanding production systems from growing. How the restraining aggregate savings would affect the movement of funds between ‘producing’ and ‘non-producing’ investments I have not really thought through. One part seems to be that businesses would need to give their profits to their shareholders, to be spent, rather than to use them to grow while the whole economy is trying not to.

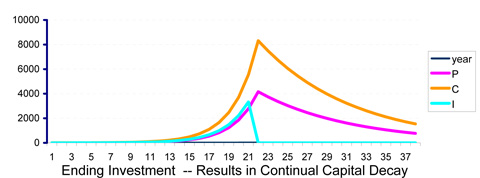

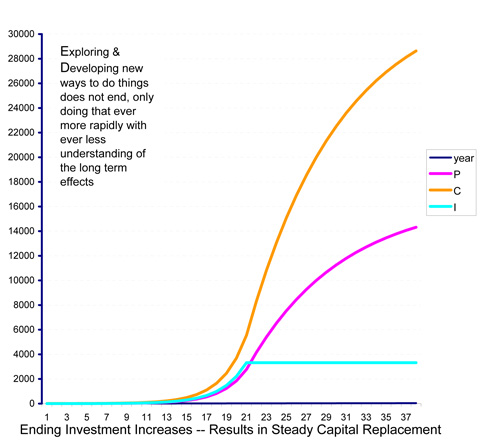

/In the absence of resource constraints the simple model for the economy (scroll to figures for quick image)then naturally stops growing exponentially, and converges on a limit. That shows a systemic change in direction, from “diverging” then “converging” toward a sustainable level. We have resource constraints, though, and lots of institutional snags to run into. So the institutional professionals who have better tools than I do need to study how to make the changes in their own procedures, to satisfy the basic principle, to keep the economy profitable and avoid hidden liabilities of pushing the limits of fragile systems of other kinds.

I suppose much depends on the answer to the first question but, in general, money spent on anything has a multiplier effect. Suppose I ‘do good’ by building housing for the poor–this directly consumes considerable energy and material, pays the wages and salaries of construction workers who spend it first on their material needs, and may stimulate capital investment by the construction industry. All this means additional material throughput and, presumably, profit for suppliers who pay their employees who spend their incomes on… (etc.). In short, it’s not immediately clear to me whether the shift in spending would result in the necessary reduction in consumption. Do you have quantitative models that show otherwise?

/For the economy to remain profitable, and so also to optimize the incomes of investors themselves, they need to choose “good works” that don’t add to the economy’s resource demands. Investors are good at what they do because they have an “eye for value”, now used to choose what to spend money to maximize their own returns. In aggregate that behavior is ending up impoverishing the economy by over-investment, though. So now they would need to look to developing an “eye for value” for making the economy as a whole healthy, as a way to restore better market rates of return (now near zero) for their investments.

Similarly, I am confused by passages such as this: “The effect would be experienced as a tremendous relief, as it became clear that the mountains of unearned income would not vanish in a financial collapse (as usual), but would be steadily turned back into earned income and profits again.” If the unearned income is turned back into earned income and profit, the material effects–increased capacity to consume on the part of the beneficiaries–might be counterproductive to the goal of reducing energy and material throughput. Are we necessarily further ahead?

/The markets try to guess the future, so we’d be instantly “further ahead” in their eyes for nipping a collapse in the bud, relieving the markets of the anticipation of the dead end ahead. Again, there are lots of complicated interconnections between the “betting world” and the working one. At the limits one can be confident that the real world needs to remain profitable for the financial one to be stable. People with better tools and knowledge of the details than I would need to study it, and then implement institutional changes in a graduated way. You’d want to watch and see how the economy responds, as a way of discovering what needs to be adjusted in the process.

I’d appreciate your help in understanding what I am missing here!

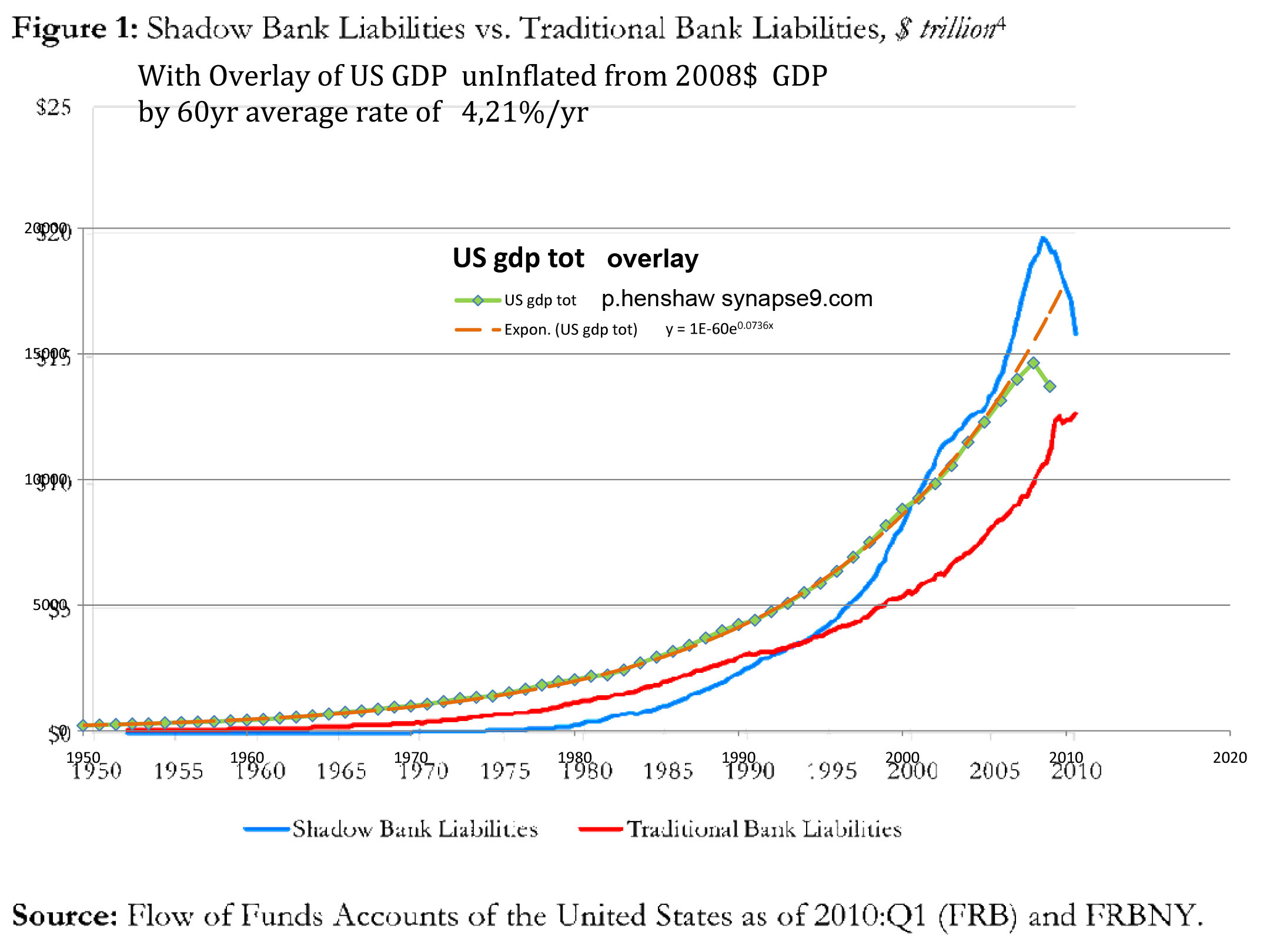

Let me rephrase the problem in terms of the pseudo-separation of the world of finance from the real economy. People make huge profits from trading paper (a phenomenon based on the inflationary impact of greed in what are really debt-financed legal ponzi schemes) but are not engaged in any truly productive activity. Nevertheless, the money ‘earned’ gives traders and ‘investors’ alike access to material goods and services produced in the real economy. The problem is, that the growth of finance capital now vastly out-strips the growth of this real wealth (manufactured capital and goods) and over-production/consumption of the latter is driving the decline/extinction of natural capital. This will eventually lead to massive inflation–debasement of the currency–and both socioeconomic and ecological collapse.

You point to one of those extra sets of loops that I think would be called the “shadow economy”, in which salaries have been paid to people for creating (in my opinion) a purely virtual economy, using “creative accounting”. The financial people will have to look at how to unwind that. I’m quite sure it is built on an assumption of limitless growth in the real economy, as all of economics is, and when that expectation changes upon adopting natural growth principles, a lot of standard procedures might not work as before.

In short, we are trapped in an economy where the bulk of money ‘wealth’ creation is not based on the material world. The question then becomes, how to reconnect the money supply and hence the economy to biophysical reality, i.e., to a sustainable level of energy and material throughput . Some would argue that this could be achieved by returning to the gold standard, for example–supplies of gold grow at an ostensibly more manageable 1-2% per year.

/Ultimately all money is a token for material goods and services. I think we agree that finance has gotten into a lot of fakery, such as the “shadow banking” system (discussion) which seems to have grown to become larger than the real one (historical trend), with only money and no wealth created. I might be wrong on that, but basically it does seem there’s a lot of unwinding to do.

/I think people will discover they borrowed a lot of money from themselves and things like that. Executive decisions will be needed on how to reset the debt instruments of many kinds that attempt to guarantee infinite growth. If it was necessary to do that globally, one would probably need some rules of fairness, and might either discount the value of accumulated financial earnings (alone) or print money to give to wage earners in proportion to their lifetime earnings (alone), or both.

I guess you are trying to achieve the same thing by redirecting profits from reinvestment in financial instruments to ‘good works’ but, as noted above, it’s not immediately clear to me how much this would inhibit actual material growth.

/Well, yes, the motivation of people to do and have more will still be there, but with returns on investments being recycled as income to wage earners instead of compounded to multiply investment, you also end the automatic compounding of political influence. The increase in wage earning relative to finance earning would also empower wage earners too. The combination, along with everyone stating to “get the picture” would make the system far more responsive to the kind of sustainability policy ideas that people talk about.

In any case, we have two more questions not addressed by these or any other approach of which I am aware. First, would a sustainable level of material throughput be sufficient to support even the present world population at an acceptable material standard? (and if not, what do we do?). Second, how do we convince those benefiting so from the status quo to shift to any proposal of the kind we are discussing? Their material status would be dramatically reduced. In general, people satisfied with present outcomes will not be motivated by logical analysis, moral suasion or even the threat of disaster.

/The first question is dear in many people’s hearts, but we’ll have to face the fact that the inability of people to take care of themselves is not anyone else’s actual responsibility. If we’re lucky, people will wise up and realize that it’s been their own choices mostly that got them in trouble.

/Aid givers are responsible for their being so uncoordinated, too, and working against their own purposes by not making aid contingent on community development and things. If we all get cooperative and it becomes a common purpose to feel proud of how we responded to the crisis, I think most of the worst hazards will be avoided. We’re in real jeopardy on lots of things, not just population, after all.

/To get people to agree who now benefit in the short term (from helping drive their own economies toward collapse) it will take the usual “viral movements” that reach “critical mass”. You can see a sign of the Occupy movement joining with the NO Austerity movement, as a potential force for change, though not for being smart about it. Those things can go the wrong way, and often have.

/As people get serious and focus on why investment funds are endlessly multiplying, and actively bankrupting all the world’s high overhead economies, they’ll also notice others who are consuming larger and larger shares of the world’s decreasingly affordable resources, for short term investor profits. I think people seeing that will feel a real revulsion for it.

/I’m not sure what community would be first to respond constructively. It might be the great population of ethical business people and investors, who find it impossible to keep doing businesses with others who try to cheat and take advantage of those respecting the principles.

In short, arguing for sustainable levels of consumption and more equitable income distribution has not been effective historically and is less so today as what Boulding called ‘cowboy’ economics holds sway. Individualism, instant gratification and greed combined with misinformation and chronic denial of science has swept the world, particularly the US.

/Yes, that’s what we need to get past. If people discover that continually accelerating our resource depletion is no longer making us rich, a lot of delusions might fall away. We’re seeing that presently with both Europe and the US running into financial trouble and unable to restart their consumption booms. Growth has become unaffordable, naturally, as the looming crisis starts with nature starting to turn off the faucet.

/So I think we mostly just need to help people see the natural process occurring. I tried to do that with my article last spring, on why prices for all key world resource keep going up as a group all at once. A decisive moment for Investing in Sustainability

I increasingly believe things will change only with catastrophe including the possibility of a tsunami of civil insurrection (of which the Occupy Movement may be the initial ripple).

/The big mistake I think people have been making is thinking the problem is caused by selfishness and ill will. It’s actually that our self-interest is misguided. Nearly every professional’s top economic priority is to maximize the compounding of their financial earnings,…after all (i.e. to maximize the problem). No one has been pointing out to them that money is a token for physical systems, and compounding the latter till it quits, makes the economy quit.

/So, I think it’ll more likely be professional communities that include independent thinkers who also understand how things work. They’d be quite able to realize the error of participating in a world plan to exhaust the earth as fast as possible. I think they just need to give some attention to what is physically happening.

Cheers,

Bill

/likewise.

Thanks for the good questions, they may be useful to others, too.

Jessie