This is an exchange with Frits Smeets on Azimuth, John Baez’s wide ranging mathematical physics blog. The original topic is the 12/13/11 “What’s up with the solar transition“, and why isn’t it happening when seeming so “logical” to so many.

See Also:

SEA Energy Accounting: far more holes than cheese 3/9/12

– Self-organization as “niche making” 3/25/12

– Principles for detecting and responding to system overload 9/4/12

– How mismeasures steer us wrong 10/26/12

The basic problem is that systems that are highly organized as cells of complex relationships and work by themselves, like the great proliferation of systems that develop by growth, the working relationships between their internal parts is untraceable. So other parts of the universe “out of the loop”.

___________

In a world of systems leaving us “out of the loop”

an observer’s view is riddled with holes,

like Swiss Cheese!

The exchange starts on that topic, and in the last two entries turns to the deeper problem of why the natural holes in our information about nature are missing from the physicists notion of a world describable by equations, or “phase space”. fyi, you might browse at the start and read carefully toward the end.

-

Frits Smeets says: 1 February, 2012 at 10:29 am

There’s this thing I can’t get out of my mind. The real problem with solar energy isn’t technological, I’m confident engineers can & will take care of that. Nor is it a matter of finance, although I agree with P.F. Henshaw’s point about reform of the financial system, i.e. allocation of investment funds on the basis of real cost calculation.

The problem is that solar energy is the ultimate threat to (geo)political entanglement of interests. Let’s face it: since the breakdown of the Berlin Wall international politics is not about territory, it is not about ideology, it is mainly about securing fossil energy supplies. Solar energy is the sword that threatens to cut the knot. Again, I don’t doubt that engineers and financial project-managers can take of their businesses – if we let them.

Frits, It’s very true that changing ideological systems takes more than having a practical reason to do so.

It’s not just the “vested interests”, it’s all the kinds of systemic integration of systems to work as a whole, making them more resistant to change than the popular “single value theories” might suggest. John Sterman of MIT has looked at the great effort it takes to build models that will expose those “hidden infrastructures” of systems that develop by growth. My work is often about discovering the hidden barriers to change, and understanding why they seem so easy to grow and unexpectedly hard to change.

Tonight’s news was about the storm damage to overhead power lines. It seems to never pay to put them underground if they started above, so much other stuff has to be moved. It’s the same for technologies, that become uniquely integrated as they grow, as people fit in new things to complement what was already there. The starting points of growth (as a process of accumulative design) generally need to be part of any future. You see that in diverse examples to how evolution never loses its origin to how the roads around Boston are generally just expansions of old cow paths and wagon trails.

For solar one of the problems is fueling, that where electric cars get recharged won’t correspond to where people get other kinds of services for their cars. The distribution of gas stations was based on getting full service at a quick stop. Electric recharge will be for only one service, leaving the car for a long time… and so incompatible with the geometry of car service habits without a other kinds of change too.

Ideological rigidity of that kind develops too. How professional and social languages generally adapt to fit their environment produces history dependence. Local language often becomes integrated with social roles and “frozen in place” as a “silo” of thinking, and a mental fixation for the social networks involved. How “sustainability” developed as a social movement around increasing resource supply rather than reducing demand, extends supplies by accelerating actual depletion, is a kind of trap that frozen thinking in a changing world produces.

I’d love to know it there’s an actual literature on the subject. The problem is also discussed as “systems inertia” or as “scar tissue”, neither of which gets at the real source of the natural resistance to change for things that are already built. It’s that changing things that are already built means reorganizing them too. I discovered that as a pivotal insight as I started my work in the 70′s, and that it conflicted in a big way with growing the economy by changing resources and technologies ever faster as a way to solve resource depletion by substituting new ones all the time.

So, I agree with you, that various kinds of “geo-political entanglement” will create stubborn resistance to converting to solar. Organizational rigidity is also a natural property of all things that develop by growth. I first noticed it affecting my work on passive solar in the 70’s, which has been economical in many ways all along but mostly never adopted. To make good use of passive solar you need to adopt a “solar ideology” of a sort, and become attuned to the variations in weather as a way to live. “That’s just not how people think”, is what I ran into.

P.F. we’re talking about natural resistance to change things that are already built. For one thing, we must not forget that we got were we are through our policies – and policy is the only way out. There’s no way around it. So try this as an exercise. Changing from fossil to solar implies the relocation of the bigoilwar taxdollar, for starters. Which means transforming the military-industrial complex into something else. For obvious reasons that’s not going to happen unless people get lured into it. And the only way is ‘show, not tell.’ Now imagine a mayor or senator who wants to start a pilot project and asks your advice for the trip. I don’t know what your advice would be but you’d better take account of five epidemiological rules of thumb:

– goal-oriented design is rigid, means-oriented design is plastic.

– energy demand (question) is quantitative, supply (answer) is qualitative.

– quantity is a product of measurement, numbers is counting.

– you never know what rule operates to explain any open series of numbers. New facts change rules.

– maximization of the value of any variable equals shortcuts equals loss of flexibility.

I guess any mayor or senator gutfeels that the risk of rigid design is its sudden death. What he probably doesn’t know is that the risk of flexible design is its possibility of new pathology. There’s no easy way out of fossil energy and no easy way into the sun, yet it has to be done and since we’re consciously trying we’d better be prepared for mistakes during the process. The way to be right is to accept the possibility to be wrong. That’s as far as my imagination gets and why I end up with the above rules of thumb.

OK, One also might apply your own principles to the starting definition of the problem as “solar transition”, and find perhaps that it’s actually a rigid goal-directed idea, and not sufficiently plastic to fit the real world of complex circumstances it needs to grow in. If the rigidity of the idea is part of why it’s hard to apply, the barriers it’s confronting in the rigid social structures of the old system also seem impossible to change too. So… it might help… to back off a bit and think about the big picture of where rigidity in design generally comes from.

I think it’s generally from extending a flexible design to its natural point of inflexibility. Developmental change is inherently about adding successive changes to “things that are already built”. For example, once you start a building as a single family home, it’s hard to convert it to becoming a multiple dwelling, even if the market changed and you’d like to. That’s what organizational rigidity is, a limit to what you can do with the foundations first built.

So “solar transition” may have begun with the very versatile idea of “love the earth”, but then was developed to fit a BAU growth model. It also seems an idea of simply swapping solar for existing energy systems like bubbles on a flow chart, but actually to have become a rigid strategy before finding a means of application. The existing economy wasn’t built on that energy source foundation, though. Maybe that’s why it just doesn’t quite fit.

Growth as a natural process is the accumulative design of an emerging new way to use energy. It invariably starts without great applications, but slowly finding applications for its unproven seed of new organization. When successful it then becomes an explosion of applications of what then seems like a quite reliable “great old idea”, but that also distracts us from the tentative ideas it really came from, and what the successful strategy’s real natural limits are. The first principle is that “accumulative design extends a fundamental design”. Then the natural limits of rigidity for the fundamental design are what emerge when development stops finding new things it can do, and can only be expanded by improving efficiency. I think it’s important to consider that general case when considering any particular case.

So, the “mayor or senator gutfeels” they are facing a wicked problem. They’re feeling tempted to either throw their up their hands in frustration or do something drastic and dangerous…. That circumstance is often accompanied by finding, if they look around, the one kind of rigidity they’re focusing on is part of a whole network of other rigidities. So removing the one, even if possible, would not foster change or alter the larger system’s natural organizational limits. It would just waste money, energy and social capital on efforts that would be ineffective, dangerous or truly self-defeating.

Nature’s ways of solving that kind of extreme re-design dilemma don’t include getting rid of one thing to replace it with another. Systems don’t have “interchangeable parts” like a bubble diagram does or a machine. That’s like a tempting “bridge to nowhere” approach, a lot of people DO seem to think of as their only choice, though. To avoid the high hazard of that kind of poor choice, to try a “death and regrowth” strategy, redesign would need to proceed by atrophy of one thing as some more versatile and satisfying thing takes root, using the profits of the thing being allowed to atrophy as a “cash cow” of sorts.

That approach avoids treating “what to do” as a political choice, turning it into an investment allocation choice to stop investing dead end strategies. It then lets the investment markets find something better to do. With great regularity “problem solvers” have done the opposite, though, struggling to find new ways to invest in keeping pushing the old systems toward their point of maximum efficiency, and rigidity.

Perhaps a smooth transition to solar, or something else arising organically, might have occurred already if our rigid thinking had allowed it to. For many decades now, we’ve been investing in increasing our rigid dependence on faster resource depletion to fulfill our rigid commitment to maximizing profit growth for those with the most profits, and things like that. We should have let the economy coast, to look for new ways to put down roots, allocated the investment resource for looking around for better things to do.

Well, there’s a difference between a goal and a target. It’s the difference between football and basketball. Goals are larger than the player, targets are smaller. Let’s assume that our goal is transition from fossil to solair energy. And for practical, Azimuth-like reasons Iet’s concentrate on the logical steps necessary for such transition to be feasible:

1) handling numbers. Numbers are beautiful because they are fast. They are good because they calculate precisely what we tell them to calculate. But, alas, they are not true. Any experienced piano tuner wrestling with the Pythagoras Comma will tell you so. And so did Gödel. So we have some elbow room – and so has our adversary.

2) differentiating between numbers and quantity. Numbers are the product of counting, quantities are the product of measurement. We can have exactly three tomatoes but we can never have exactly three gallons of water. Numbers are relational, pattern-like, a matter of digital computation. Quantity is analogic, probalistic, a matter of (non)consensus. Few senators realise this so you’d better realise it yourself.

3) cherry picking from the mess-to-be measured. In other words, the quantity of precisely what shall we measure & count: terawatts? barrels of oil? miles? working hours? taxdollars? Wallstreet index? the happiness curve? life expectation of (grand)children? climate prediction? Ah, lots of elbow room, so be prepared.

4) incentive imagination. In the U.S imagination is ruled by the myth of the pioneer. So don’t tell your senator why it’s a mess in the East, tell him to go the proverbial West.

To sum it up in terms of problem solving:

– appeal to sentiments (see 4)

– pick the types of quantities you’d best address to your public at hand (see 3)

– stand your ground for the types of quantity but never rake in their numbers (see 2)

– don’t forget that numbers tell a lot but show nothing (see 1)

Well, you seem to be taking off in a new direction, not where we started with identifying natural world barriers to the “logical course” of our adapting to how we changed the earth.

We were beginning to discuss what kinds of responses are possible or impossible, better or worse. Now you seem to be looking for what kind of theory to use. I think the kind of theory to use is to identify the natural world barriers and what to do about them.

As for using math, I don’t see the critical difference as between “measuring” and “counting” but more on “what you’re measuring” and “what you’re counting”. Do your numbers correspond to anything’s working parts, or are they just “statistics”. My scientific method focuses on finding answerable questions to ask, in the hopes of avoiding the calculation of precise results for questions that may not really mean much.

Following that approach I recently published a paper called “Systems Energy Assessment (SEA)” for how to count up the fuel uses required for operating businesses. The finding is really strange. It’s that because economists have been only counting up the energy purchases recorded on slips of paper that business accountants keep on file, they miss counting on the order of 80% of the energy uses that businesses purchase from outsourced services, businesses need to operate.

So, the problem then, is what better way is there to define what energy uses to count, when the real problem for the accountant is that they ran out of information to categorize? Somehow we need to estimate the total energy demand of running a business in the real world, to understand the real energy problem we face, closer than +/- 500%.

Well, I don’t feel it’s a different direction. I first gave some rules of thumb on how to deal with barriers to the transform from fossil to solar. Next I paid attention to some logical steps to avoid traps in designing a transform ‘program,’ one of the steps being to differentiate between numbers and quantities. I looked at your article and saw that what you sure did is differentiating between the two. It’s a good example of 2) and 3) of my last posting. Fine piece of work, seems to me. I hasten to add that I’m nothing of an energy expert. I’m a philosopher interested in epistemology, especially in the concept of epidemiological ‘first steps’ pioneered by Gregory Bateson. F.S.

Frits, Great! I’ve learned a lot from philosophy, but started looking at how both philosophers and scientists think of reality as built in their minds, and so a source of error. If the common currency of intellectual discussion is “looking for the better model”, I think it means we’re studying models, and not “exploring reality” in fact.

There does seem to be a real world, but it’s also confusing that “what we see is not what we’re looking at”. What we see in our minds is physically our own mental environment. That’s only a personal version of a social construct for our personal experience of the world. That’s not reality, and even hard to distinguish from a complete dream world.

I think that’s physically where the “six blind men and the elephant” dilemma comes from. We all have a strong tendency to think of consciousness as being the world everyone else lives in. It may be a “nice world” but the reality is only we ourselves live in the world of our own imaginations. In so many demonstrable ways consciousness is a world we construct for ourselves.

So, for learning how to “do math” to help us with the real world we’d need some way to distinguish features of the real world from others we create by our own thoughts. That’s tricky… because so very much of what we think about is our own fictions. The curious thing I found with SEA is how very common it is for people to theorize that the world is whatever makes sense of their information. That completely overlooks the profound gaps in our information caused by the self-managing systems of the natural world. Because they are internally organized, they just don’t expose to us how they work.

So, to counter that I looked for ways to help identify elements of nature independent of my thoughts. One is finding the bursts of new relationships that coincide with growth processes. That particular continuity of regular positive proportional change (i.e. explosions), exposes “persistent heterogeneity” in individual local processes that theory can’t explain at all. To me those seem to exist as realities outside our theory. It sure stumps the physicists and economists anyway! ;-)

So, that’s where I started using a general “two reality model” (sort of like Robt. Rosen does) as a step toward sorting out which human social realities are self-serving constructs misleading us about the real planet…

O.k. Allow me to point out two epidemiological knots in your posting where it says near the end “So, to counter that, I looked for ways to help identify elements of nature independent of my thoughts.”

The first knot is that it is impossible to identify anything independent of your thoughts. The reason is that any identification is an act of plotting perceived differences onto some map. There’s no way around the difference between map and territory – not for bees, not for monkeys, not for human researchers. No map ever covers the territory and all territories mess around outside maps.

The second knot is more complicated. Please note that your intention is to counter something, meaning that you intend to create an alternative map. The interesting thing with a map is its triple epidemiological functionality: it offers me a certain description of a territory, it more or less persuades me to accept what I read, and it instructs me (un)succesfully to follow the interests of the mapmaker.

Now, the bottom line is that you don’t trust the energy map you’re presented with because it doesn’t plot the differences in the territory you do perceive and find important. So you design your own map with the intention “to counter” the other. I’m afraid that’s where you’re likely to go astray. What you should keep in mind is that, for travelers (your average mayor or senator), maps are not related in terms of pro/contra. For them maps are related in terms of differences in descriptive relevance, persuasive potential and instructive power. The only way to transform from fossil to solar is getting travelers to buy the new map.

Well, that’s semantics for you! It leaves traps for our tendency to not consider the multiple interpretations of the words available. I do acknowledge that all my meanings of things are in my mind, whatever name I might give them. It’s the things of nature that I have no way to define in my mind, except by “pointing” to something else, that I find opens my “maps” to a real world “independent of my mind”.

Pointing seems to be the normal use of words for referring to things by name we have no way to know how to define. Referring to them, like saying “is that a rose” or “pass the plate”, gives us a point of takeoff for exploring or interacting with complex subjects, needing only a simple definition for pointing to them.

That seems imprinted in the evolutionary design of language, too. Looking at root meanings of words they seem to fall into categories, in my view, with all the old ones mostly meaning “like”. “Like what?” is the question that seems answered by “undefinable things observed that people wanted to refer to” and found words a good way “pointing” to those otherwise undefined subjects.

What confirms to me that directing our thoughts to “things not of our thought” is happening is the reliability of my being able to then explore their features and find out valuable things I simply never could have imagined about them.

Seeing an apple produces a meaning in my mind using the metabolic energy of my body, some of which may have come from eating apples. Apples can, though, be found to have been produced by a tree, using energy direct from the sun not having gone through my body, for example. That the tree may have been planted there because I like eating apples doesn’t seem to mean the same thing as “I created the apple in my mind”, so a separate question.

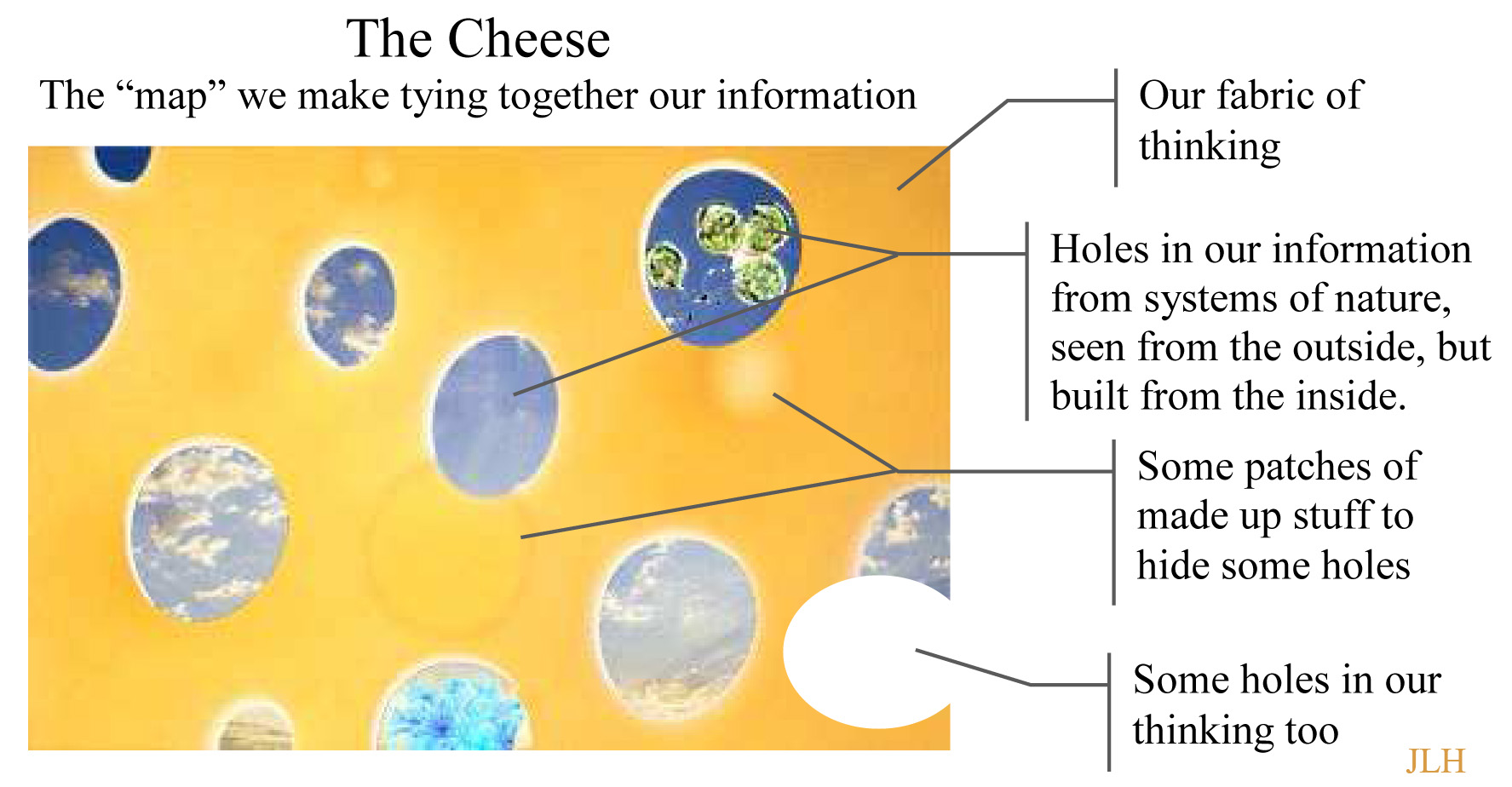

So what in means to have words that point to things of nature, that exist independent of our minds, is that we get a “map” of the world just chock full of holes. Those holes are where we can usefully and reliably mine information for our maps that fit “other realities”. Another value of having “maps” full of holes, that “point to” things we can locate but not define, is it lets an observer separate the two aspects of reality in their own maps. It also allows two observers to confirm they are each discussing their independent explorations of *a corresponding hole* in their own maps. The method of pointing that creates the “hole in the map” itself, can be defined and communicated.

Without all that I guess it’s natural for you to think what I said was presenting a contest between a popular map and one of my own invention. It’s the explorability of the holes in one, and lack of similar explorability for the other, that is the difference I think makes more of a difference.

No, it’s definitely not semantics for me, so I didn’t read that remark : )

What I do read is that you concentrate on the map-territory relationship, whereas I concentrate on what a map does in terms of epistemology. Interesting difference.

Let me sneak up from another angle. In discussing the map-territory relationship you use the phrase ‘pointing to.’ That is a very mystifying way of putting things, and I’m not talking semantics. Maps point to nothing, what they do is suggesting. They are metaphors. To be precise: a map transforms, by way of some code, classified differences of a certain logical type into another logical type of classified differences. High/low in the love affair gets transformed into eyes opened/eyes closed in the poem; High/Low in the hills gets transformed into red/blue on the sitemap; High/Low in oil pipe pressure gets transformed into +/- in statistical flow charts; High/Low in expected energy demand gets transformed into a up/down of the Wall street index. Metaphor rules.

If I understand you correctly, you use a map as a heuristical tool for spotting uncovered territory, ‘holes,’ in a in order to get them explored. That is an elegant & efficient way to travel and I have no problem with that method whatsoever. What I want to get across from an epidemiological point of view is the idea that maps have the triple funtion of metaphor: they describe, persuade, and instruct. In short, they are a beautiful mess. The beauty of it is obvious. A mess, because a map can & will be used by travellers having intentions completely different from the motives of the maker. That’s why I jumped in on this blog: to remind that the transformation from fossil to solar follows the rules of metaphor. Hope it helps.

Well, even highly articulate people tend to make assumptions that create insolvable problems for communicating, I find more and more it seems (1). I’m not exactly talking about the meanings of “the map-territory relationship”. It’s not that I’m not interested in that, but initially more interested in how a map is grounded, and ways to discover whether it is connected to ANY territory. You might also think of that as a question of how to “tether the map” to the territory.

The important part seems to directly conflict with the physicist’s usual notion of “phase space”. So I need to find devices to bring up that part without being dismissed before getting to discuss them. It’s the quite interesting vast gaps in our information for any natural system we can readily observe from the outside, but is evidently organized and operated from the inside.

Those critical large gaps in our information are what I refer to as “holes” in what is observable to us. They are then naturally reflected in any information map. So far they seem to be completely missing from the normal concept of phase space, however. It makes an enormous difference for understanding why so much of nature doesn’t behave like equations.

So, I’m interested in finding a way to discuss those odd holes (or “voids”) in our “maps” of definable relationships. They seem to be filled with identifiable natural structures from “another reality”, that we can readily locate and are what give original meaning to the maps we make, but still remain holes in our information we can’t define. So some version of “pointing” seems needed.

For example, if I say in conversation at your home “your daughter looks ill”, where would you look to discover what I’m talking about? Would you look around the room to see if she is there, and at her face to see if she looks ill, perhaps? Or would you look up the words in a dictionary in hopes that will tell you what they mean, or would you maybe look to your own feelings about her and me, and try to guess why I would intrude in personal matters I know nothing about? So it’s a question of how the map tells you where to “point” your attention.

I’m commenting here a bit like you, I guess. My interest is to find anyone curious about how things like “the transformation from fossil to solar” needs to involve a natural world outside our definitions, a world of material relationships not contained or containable in theories or explanations, a “non-map” world that needs to be navigated not explained. So to add to your list of the map functions of interest “to describe, persuade, and instruct”, I’d also add “to question” and “to misrepresent”.

“To question” refers to the need to go back and poke around in the voids in our information to find clues about what nature is doing in there. It can lead to new discoveries and help resolve contradictions or identify contradictions, as when exploring “promises too good to be true” that may appear in your map.

“To misrepresent” refers to the need to have doubts about the patches your map making process naturally creates, made for covering over the cracks and voids in your information with useful fictions. They’re partly of interest for being able to turn your map into a kind of ungrounded fabric of magical thinking if you’re not quite careful.

1)Did we turn “Big Media” into “Big Brother”?

____

and following on 2/6/12

From my epistemological point view your approach to “a non-map world that needs to be navigated not explained” shows two ‘holes’. It skips the fact that you can’t navigate without some map. And it skips the fact that a map for transition from fossil to solar inevitably wil be a map of maps.

In the business of scientific (re)search ‘map’ reads as ‘hypothesis.’ Hypotheses get tested, verified, falsified, corrected, etc. in cycles of ongoing research. It’s in the process of cycling and recycling where the functions of ‘questioning’ and ‘misrepresentation’ take place – not in the hypotheses.

Well, the epistemology use does require adjustment. Reading a mental “map” of your own construction is a different exercise from being led by the responsiveness of things in your environment you can identify, but are unable to define, explain or predict. That is like reading a map you didn’t write, being drawn by something else.

It’s like smiling at another person, you just don’t know what’s going to happen. Without what DOES happen, you often can’t know how to proceed from there. So, that’s not reading your own “map” but “navigating something else’s” that remains undefined as you are more or less groping along. That’s the switch that lets you out of assuming all the world is a subjective construct, the clear navigable evidence that you’re “not making this up” but being led by the constructs of something else.

So, as I think Robert Rosen suggested, that leaves scientific methods a necessity of needing to use both those “map using” methods. One is making and using your own map and the other is finding and being led by the “?maps?” of others. As the two quite separate orientations, I think probably for semantic coordination they’re better termed as “two separate realities”.

_________