3/15/10 This is an edited foreword for my 3/13 post and a P.S. It’s really about deflecting the false impression made by an unfamiliar view of historic data, so not of general interest, I think.

A recent note came from Charles Hall, with two interesting things. He passed along thePeak Oil Review pointing out again how oil prices are edging upward even as the economy slips. Continually rising prices is a natural symptom of trying to grow with diminishing resources as I offered a theoretical basis for in “Profiting from scarcity” last year.

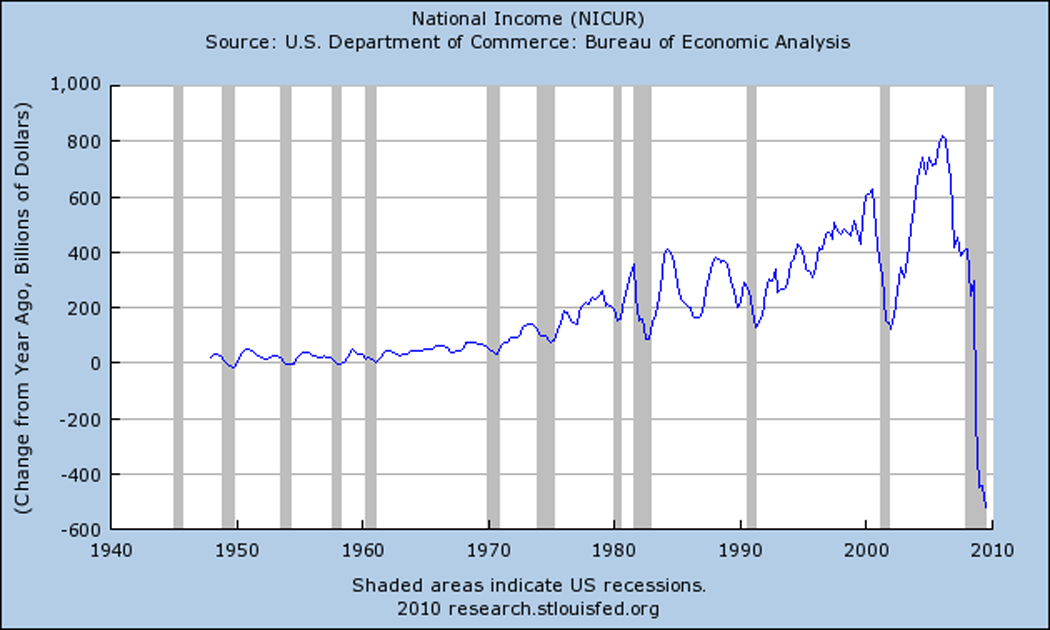

Then he mentioned a provocative series of graphs from Nathan’s Economic Edge. These are graphs of first derivative rates, with the one below showing rates of increase of US national income fluctuating wildly as “steady growth” has been frequently broken by recessions. It also gives an impression like the increasing roller coaster experience of keeping up with economic change.

The real question is why would the irregular rate of economic growth remind us of the increasingly desperate struggle it has been,

The real question is why would the irregular rate of economic growth remind us of the increasingly desperate struggle it has been, and what does that tell us. I think there is a basis for saying that it’s because we are in fact struggling with an increasingly impossible task, with recessions being the times when we discover what increasingly radical changes we all have to learn to keep up with.

It’s a complex question, though, and in the first draft of this post I mistakenly encouraged the visual appearance of ups and downs in the rate of economic expansion to be interpreted as financial instability. It only shows increasing instability if you associate it with the successively steeper and riskier learning challenges it represents too. Growth does in fact push people to do more with less by ever bigger steps relative to our own learning capacities.

As all the kinds of environmental complication and resistance to growth increase, that struggle is ever less of a success too. As toward the end of a Ponzi scheme or financial bubble when people start to get sloppy and take risks that later seem inconceivable, being caught up in juggling increasingly impossible tasks strongly affects your judgment too. That is the more complex side of the story.

For now I’m leaving the post as it was, though, hoping you can read it in that light and just adding a P.S. at the bottom. The connection between financial stability and our increasing struggle to keep up with accelerating change is what needs to be discussed, and I hardly touch on it here.

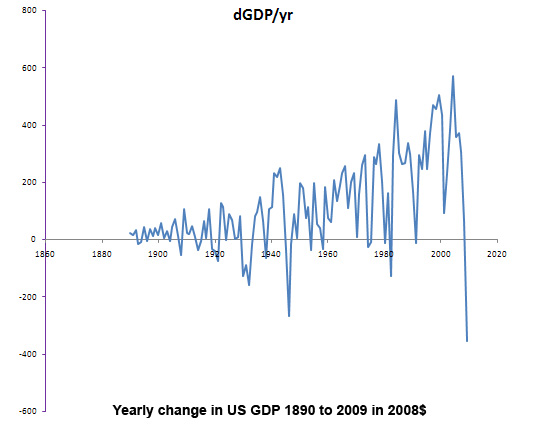

The ‘P.S.’ shows the pattern of growth volatility all way from 1890 to the present. It’s been much the same all along, and I’m sorry I forgot to check that before taking the suggestion from the recent trends that the pattern was changing dramatically. It’s not.

The long trend is of an increasing rate of economic expansion with frequently large interruptions exposing some of the tumult it involves. The whole progression of increasingly challenging learning tasks is what’s increasingly unstable I think, but the graphs themselves don’t show that.

Seeing recessions as marking time in our taking on physically bigger, more challenging and ultimately unachievable efforts to reorganize and control the earth is what I’ve been trying to explain since I understood it, in the 1970’s. Growth may seem to have been stable, using it’s products to multiply the process, but it’s hard to ignore the constant interruption by painful recessions, or the completely unmanageable nature of the actual goal of accelerating forever.

Where the “rubber hits the road” for that question is when the growth process runs into natural diminishing returns on its increasing investment of our efforts. By all counts that was in the 1950’s when the economies stopped finding ever more bountiful and cheaper resources and began finding increasing costs and complications as their return on increasing investment instead. My first graph of that, from 1979, is below.

****************************************

The problem was correctable 30 years ago when I first noticed how it worked and it remains correctable today, if and only if (however) people see it as a physical process having a physical cause. It is a physical process our cultural conversation does not yet have much awareness of, however, so our increasing struggles to fix things remain less likely to make things better than worse.

This first graph shows U.S. National income. The normal physical process that would cause this kind of increasing instability is that economic growth is produced by our continually changing economic strategies by successively bigger and faster steps.

That leads to the process becoming an series of ever more perilous crises for coordinating the parts of the economy as they each try to keep up. It’s the lag times in discovery and response to ever more complicated and difficult changes in methodology that do it. They naturally become ever more uncoordinated,

I think that’s what’s happening and that what’s physically driving it is our habitual use of investments of all kinds, financial, human intellect, material resources, etc, to multiply our investments in speeding up our changing strategies, by “constant” %’s. We make the mistake of thinking constant %’s change maintains stability when it multiplies imbalances we have to run ever harder to catch up with.

Regular % increase is how nearly everyone defines our self-interest. It seems to be in many ways, except it also destabilizes the physical process of adaptive change on which it depends… If we had just stuck with one thing for a while, it would have lasted for a long while. This fault in how we keep accelerating our way of changing was correctable before and is still correctable now, if people come to understand what the real cause is.

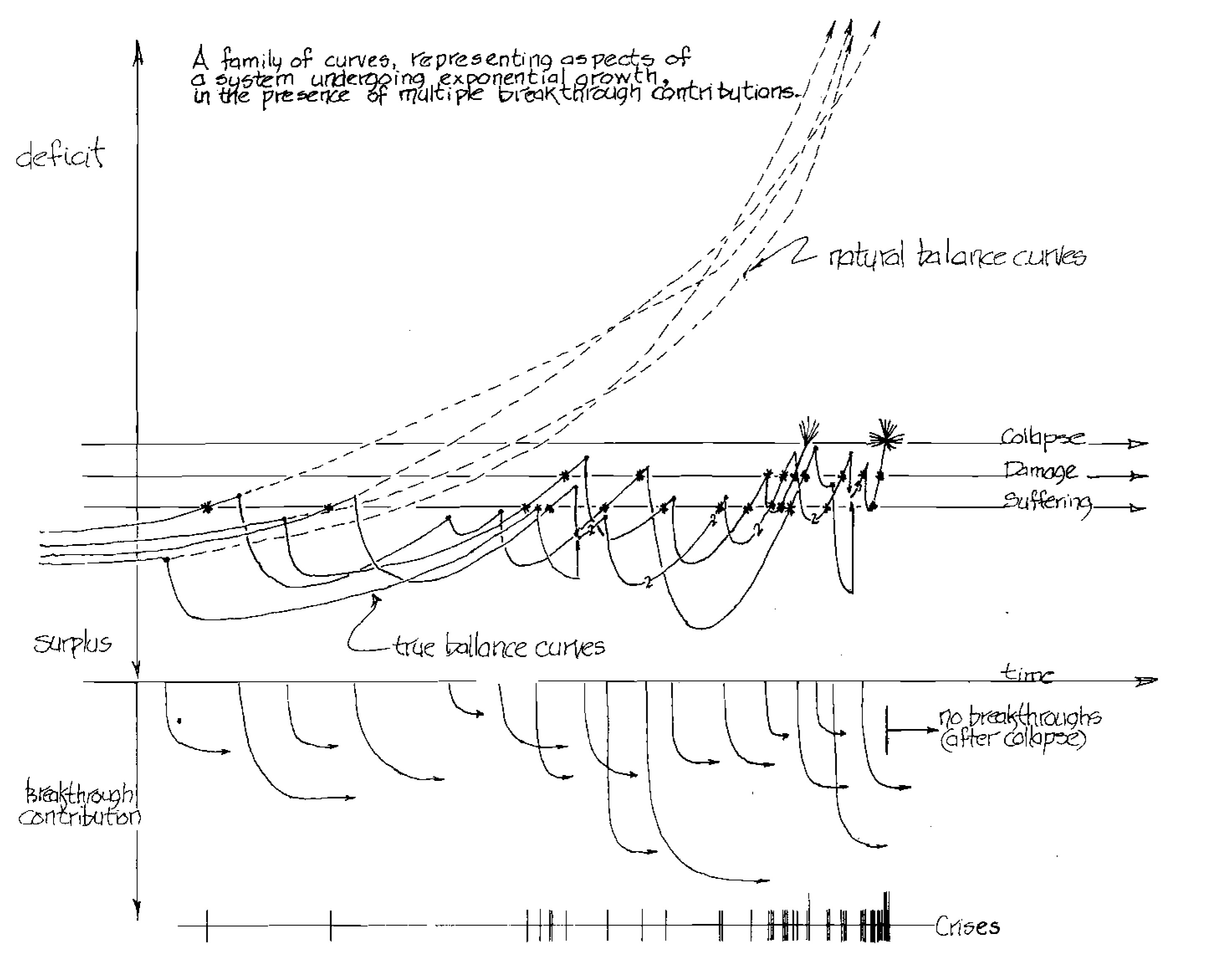

This 2nd graph illustrates my early thinking on the escalating crisis scenario for “growth induced collapse”. It’s an image of multiple technology sectors needing to cooperate and each making successive technology and resource discovery breakthroughs.

After the point of diminishing returns regularly bigger ones are still needed but smaller ones are found. So the frequency and complexity of changes in methods increases instead, and toward a point of failure. It’s a completely natural interplay between delayed response and compounding growth stimulus.

The graph is from my first paper on the subject “The Infinite Society” as part of a self-published book of essays in 1979 including “An unhidden pattern of events” discussing my early studies of a science of uncontrolled natural systems. It’s about how uncontrolled natural systems that become unstable are a major part of the eventfulness of the world, and why some are quite predictable.

I’ve done much more since, except for figuring out how to get people to go far enough in differentiating between our cultural realities and reasoning that animate our minds and the physical systems that animate nature …

Maybe that elusive key for most people discovering what is apparently “hidden in sight” would be to call these things “unnatural systems”. They come from somewhere other than where people “naturally look”, i.e. not found in the values and explanations in our minds we most commonly think of to represent nature and the economies.

Where the animating processes of the world are actually located, in that sense, is in “unnatural” systems that have no values or purposes but still somehow work by their own internal designs… That the real systems of nature are in that sense “brains with no thoughts” is not what people have shown much interest in yet.

If people just go as far as they can trying to understand it, and then asked for help, some of my methods would show how to continue on further from wherever they got. If we don’t ever notice how these “unnatural systems” control most of our choices, well then our own ideas of self-interest won’t connect with them.

Why we have had an increasingly unstable world has never been that we were not trying to do what was right, is my way of explaining the contradiction between good will and bad outcomes the world over. Our multiplying crises seem to be largely inadvertent consequences of pushing our systems beyond their natural limits of stability, unaware. The root error seems to be not realizing that the animated parts of the world are not located in our thinking. They seem to have lives of their own in that sense.

pfh

**************************************** P.S. 3/15/10

For another view here is the graph of yearly changes in US GDP back to 1890. From this view the first question is why the rate of increase in GDP has never been in the least bit stable, always lurching from recession to recession. It’s rare to not have a decade without a year of economic decline.

The basic subject I raised was whether growing economies force us to change strategies more frequently as we run into natural limits. If you think of recessions as “the new upsetting the old”, then it seems growing economies force people to learn how to cope with that quite frequently, to make leaps of change in their lives and the world. The leaps get bigger is what I’m interpreting as a decidedly unstable progression.

It takes realizing that the tasks of relearning get bigger for people in absolute terms because our minds are the same and the actual changes are materially bigger and far more complex at each stage. So the systemic volatility that looks sort of “constant” in proportion to GDP causes people to make ever bigger, faster and more complex changes in their own solutions.

Models overlook that. Models are just curves on paper and don’t show people are taking on increasingly complex and risky learning tasks. They also doesn’t show when people are increasingly misunderstanding the problems ahead. It’s apparent in this long term trend curve, though, that the present frequency and severity of the business cycle as about “normal”.

As you get closer to natural limits, finding ways to grow by accelerating the use of resources in short supply would be less an less sustainable as an economic strategy. Mature economic systems that needed resources that no longer exist would fail without being replaced. These days we do also seem to see whole industries come and go with the fog… as it were. The music industry an now even journalism are sort of “gone with the wind”.

The biggest factor destabilizing growth now may be the permanent switch to scarcity pricing for all our limited resources, as resource supply is then no longer responsive to price and demand. That’s not in our economic models is part of the big problem…

As I discussed in “Profiting from scarcity“, I think that switch may have already happened, as seen in the worldwide commodities price explosion this past decade leading up to the 2008 financial collapse. For six years there was a ~25%/yr price increase due to globally unresponsive supply for food and fuel resources as peak oil supply occurred at the same time as peak oil demand. It’s not in the models, but I think it happened anyway.

pfh