Attachment for CAUN Post 2015 - UN Consultation on Environmental Sustainability

New Institutions for

a Global Commons:

proposing natural design for a human

ecology with self-regulating sustainable development and finance

Introduction - Proposal I - Proposal II - Proposal III

General Introduction + Foreword & Original for three 2012 Rio+20 Dialogue proposals

a common trust and place to enjoy being at home

Helene Finidori and I, Jessie Henshaw, submitted proposals on a commons approach to sustainability, that got attention in the 2012 Rio+20 Dialogues. They outlined ways the UN could foster development and ease the world’s combined economic crises, by helping people make choices based on the world’s common interests.

Helen’s was a general cultural vision and model of the need for new institutions to pave the way to solving the world’s problems with a commons approach (1). My two proposals were each for new global economic institutions to allow free market economies to follow their own common interests to become eco-balanced and self-regulating (2,3). Both followed general principles of natural design, visible to anyone in how nature creates enduring complex systems that thrive in growth, and then also remain creatively evolving and thriving in stability.

The notable difference between these approaches and the numerous other models for world sustainability is that they don’t rely on government regulation as the primary means of protecting the economy’s self-interests. The models offered by Herman Daly in Beyond Growth, Gus Speth in The Bridge at the Edge of the World, H.T Odum in A Prosperous way down and Tim Jackson in Prosperity without Growth, all use science as the basis of direct government regulation of the world’s resource use and development decisions. They don’t say how government would either make successful choices for the economies or fail to avoid the “race to the bottom” that has always foiled regulation of conflicting self-interests before.

The common approach starts with the cases where those competing interests can be led to the information needed to understand their own common self-interests. It’s then in their interest to use their positions to collaborate on creatively solving their own problems. Very few new rules are needed. Natural choice and fiduciary obligation then applies to making the right choices.

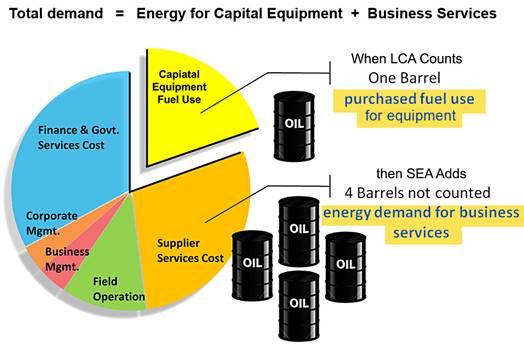

Figure 2

The difficult challenge of a commons approach is finding the “boundary crossing” ways of communicating with other stakeholders, those having different intentions and speaking of different parts of the problem. Some important economic values can be reduced to numbers, like identifying when a resource is overinvested and how much any product relies on using it. But finding common ground for collaboration with people with conflicting interests is hard, even if obviously possible because it’s necessary.

Still, the thriving complex systems of nature are the model, evidence of all kinds of collaborative systems that evolve naturally without computers to tell them how. They include biodiversity “hot-spots” like fresh water ponds, and forests, and many other kinds of thriving eco-systems. They also include the thriving human ecologies that people create, the cities and thriving social cultures, the complex emergence of new industries, etc. They’re all the same general kind of dense networks of diverse subcultures. All the parts are acting individually, hardly aware of what each other are doing, but somehow building toward their common interests.

Our understanding of the word "commons" comes importantly from the classic “tragedy of the commons” by Garrett Hardin and following debate (1). Individual self-interest can lead individuals to destroy their common resource, as when people put more cattle on a shared meadow to individually gain at other’s expense, leaving the meadow barren though, as everyone does it. So the community makes choices for being productive, that leads to destroying what was making them productive. Now we’re doing that with the whole earth, and need a better solution.

A way to overcome that is for everyone to be presented with where their choices would lead, so their neighbors of someone making the mistake can understand, and intercede in a polite way, before the community faces a tragedy from over-taxing their environment. As they all recognize that this is the new way of doing business, they’ll help each-other find ways to work together. The "commons sense" is that there's no reason not to act in our common interest, if we can understand what that is.

1) Tragedy of the Commons - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragedy_of_the_commons

2) This draft originates from the “News of the Commons” blog post of June 7 2012

_____________

Foreword

I. New institutions..

for commons-based economic models

Helene Finidori

Helene’s proposal won the voting for the “Sustainable Development as an Answer to the Economic and Financial Crises” topic in the RioDialogues vote, and good recognition! The idea is to NOT use development, as the solution to the world economic crisis, but to create new institutions allowing development efforts to work together, to serve the whole.

Helene’s idea builds on her own thinking about the nature of systems and the recognized methods of constructing commons solutions advocated by the Nobel laureate, Elinor Ostrum, collaboration that competitive interests need so the whole can thrive.

She also adapted the ideas discussed in an exceptionally wide ranging debate on the whole issue she led on a LinkedIn forum called Systems Thinking World , catalogued in Systems Thinking World discussions on the UN Call for Action,

Her more recent writings give a broad picture of her poetic

vision of the commons and her reasoning of how people can make the world work as

a whole.

-

“Commons-Sense” (Aug 2012)

-

In my dreams… the Living WE… accelerating emergence…

-

The Commons at the Core of our Next Economic Models?

Original

I.

Sustainable

development requires new institutions to cooperatively steward and manage the

global commons and adopt commons-based economic models

Proposal of May 28, 2012, with minor edits and added

references

on the Rio+20 Dialogues 2012 site: https://www.riodialogues.org/node/240649 Summary This recommendation calls for the development of a commons sector, alongside the private and public sectors, conferring rights and responsibilities to communities over resources on which they depend. This would ensure that the people who have a long-term stake in the preservation of these resources (natural, physical, intellectual, social, cultural; from local to global) would protect them while enabling the development of a flourishing commons-based economy around them. Commons are the shared resources that we inherit, create and use and transmit to future generations. Vital for our sustenance and livelihood, our individual expression and purpose, our social cohesion, quality of life and well-being, commons also embody the relationships between people, communities and these shared resources. Background It seems the current

definition of Sustainability as the ability to: “meet present needs without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs (WECD, 1987)

is not unifying enough to get the ‘forces for good’ to converge and create some

action around a shared intention." The Global

Sustainability Panel of the UN which presented its Resilient

People Resilient Planet: A future Worth Choosing report to the Secretary General last

January suggested policy frameworks based on new indicators, means for

innovation and entrepreneurship, for resilience and empowerment, incentives for

long-term investments, adoption of some forms of externality accounting,

institutions for increased civil society participation. It also quite clearly

states in its vision outline that the answers revolve around choice, influence,

participation and action, and calls for a process “able to summon both the

arguments and the political will necessary to act for a sustainable future.” So, how can political

will be summoned? How can a collective intention for sustainability be

generated? In this perspective,

it is interesting to look more closely at sustainability in relation to the

concept of commons dear to Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom and

other economists such as James Quilligan who oppose the inevitability of the

tragedy of the commons and show how commons can be co-governed through

stakeholder and civil society based institutions in effective ways. Quilligan defines the

commons as the collective heritage of humanity, the shared — natural, genetic,

material, intellectual, digital, social and cultural — resources that we

inherit, create and use and transmit to future generations. Vital for our

sustenance and livelihood, our individual expression and purpose, our

social cohesion, quality of life and well-being, commons also embody the

relationships between people, communities and these shared resources. If we consider commons

as assets that must and can be preserved and nurtured -just as private and

public assets are currently meant to be-, then we give them some materiality

and tangibility as socio-economic objects -even when they are intangible-. And

if we adopt a patrimonial approach of replenishment and growth of the commons

(whether material or immaterial) as the basic discourse for sustainable

development and starting point for new economic models, we have a ground for

creating new institutions for governing the commons and new kinds of metrics,

accounting systems and economic instruments that would help the development of

a sustainable economic and financial system and the reconstruction of the

relationship between individuals, institutions and the commons. The UN could

play a leading role in helping the constitution of civil society / stakeholder

governed institutions to steward global commons (commons sector), in

complementarity with the nation states (public sector) and the corporate world

(private sector). I am just back from

London where I attended a series of seminars by James Quilligan on the emergence

of a commons-based economy. Here are the video and transcript of the seminar he

held at the Finance innovation Lab on May 10th: How would a commons approach shape the future of finance?

Recommendation The Commons

Action for the United Nations team at the UN has drafted

recommended Measures to Shift to a Sustainable Commons Based Global

Economy as well

as Measures to Finance that shift for Rio+20 and additional documents

that are attached below that constitute the basis for this recommendation. Adopting the

principles of a commons based economy at the UN level would accelerate the

emergence of new practices and behaviors by the mainstream.

To make this happen, the first step to be

taken would be for the UN to establish a High Level Panel on the Commons. This would be a natural follow up on

the vision of the Global

Sustainability Panel, the orientation of which is much in the

spirit of the commons.

Attachments

Tags:

#recommendation, Sustainable Development, commons, metrics, commons-based economy, accounting system, externalities,

governance institutions

|