Einstein, Keynes, Boulding,

Jacobs .....

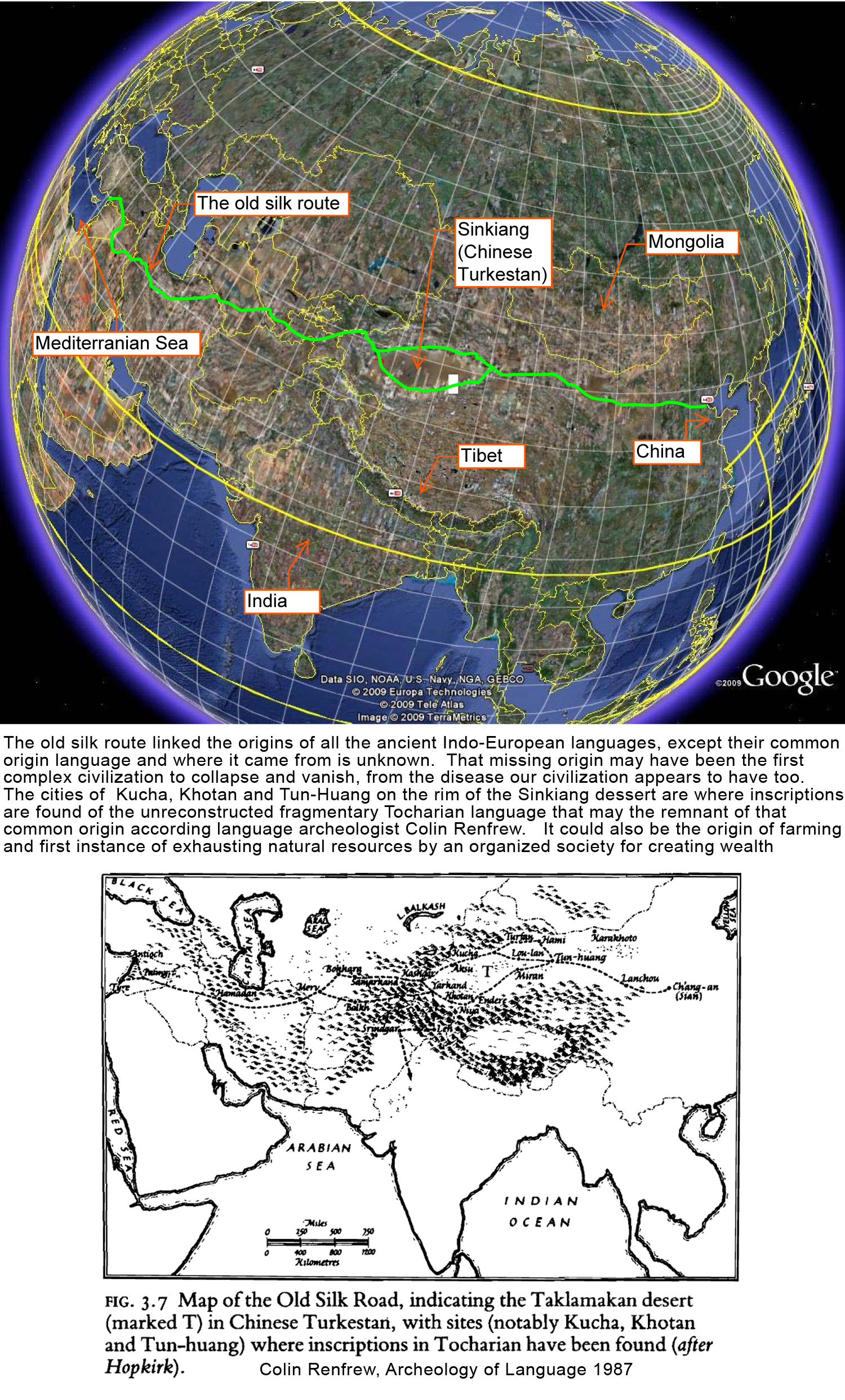

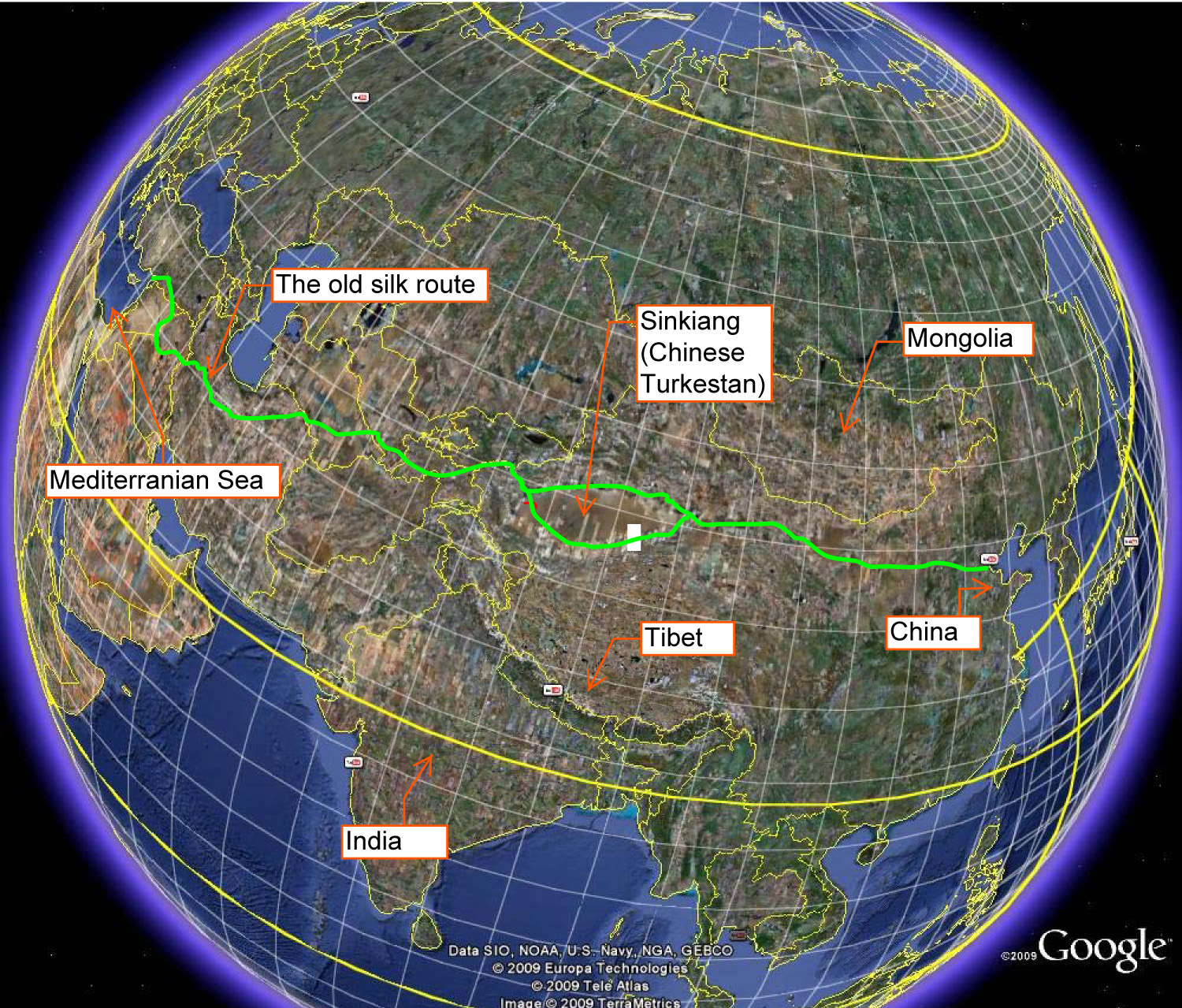

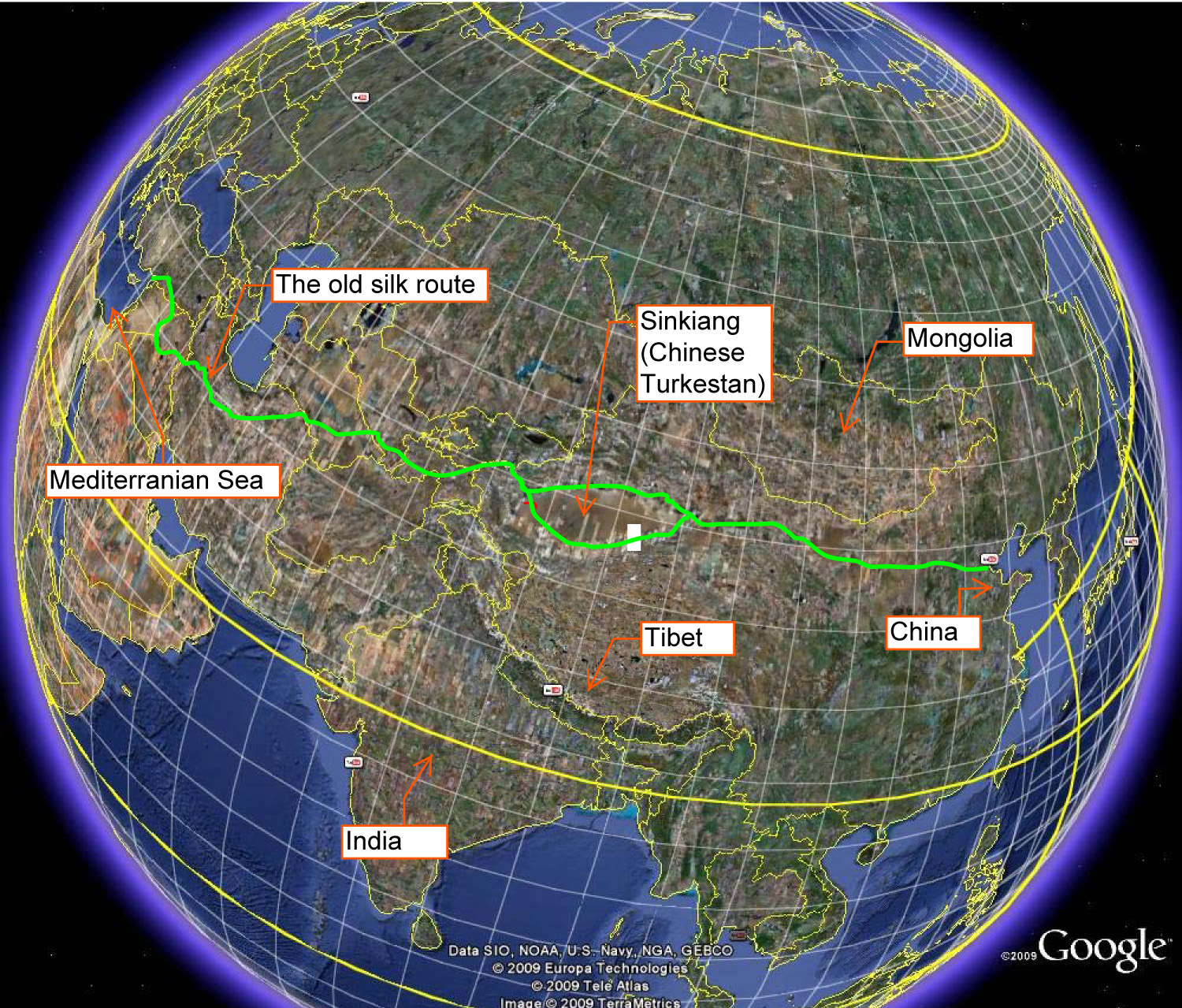

clues to

the

ancient struggle, between the natural physical world and human information and belief

may lie along the path of the old silk route:

-- why historians can't find the first complex

society, where the mother tongue of western thought developed, and then vanished without a trace...

-- compared to the view from our own collapsing

tower of Babel, looking back in time and place

of the first one.

[i.e. looking back to that important milestone in mankind’s emerging long battle with

the hazards of superstition and magical thinking]

2/17/09 (first save - partial draft), 11/14/10 (smoothing)

Why in the 20th century modern man built the wrong economic system

for its future, and now needs to deal with having run out cheap resources, and so out of

credit and materials with which to remake it into a better one, can be summed up as a popular idea winning out

over a practical one. It seems to put on display our long and great struggle

between the two ideas of reality. Is there a physical

world beyond our explanations, or just a world of explanations? That's the

question.

I came to my own very simple and clear resolution that the

world works better when considered as having both, both a world of meanings and

a world for meaning and explanation to explore, partly with the help of Einstein, Keynes & Boulding, all of whom

ended up being dismissed by the more popular intellectuals of their fields, who

went on to establish the form of science for the later 20th century, and our

model of applying technology to develop the earth. The "winners" of

science built our world around a model of nature as

being our explanations, a matter of information, not stuff. It was the

popular 'main stream' intellectuals who called Keynes idea of the climax of

capitalism (1) that Boulding also upheld (2),

"the fallacy" and described Einstein's idea that "God does not throw dice" as

"naive and immature", notably Niels Bohr, Heisenberg and Schrödinger, with many

many followers in many fields, who began a worship of Quantum Mechanics as a

justification for believing that reality was composed purely of our information,

and the world must necessarily be considered as operated by the explanations in our minds.

It was a perfect fit with our economic culture of endless growth as a model of

stability, as simply great and perfect idea.

"the struggle between the two great ideas of reality"

Indeed!

how else could one explain it? Well, the far more

practical way. If that matters, of course, the more practical way is to accept physical reality as something that

needs exploring, but not explaining. Our ideas about it

may need explaining, of course, but reality never does. That is the

view that was firmly dismissed and disparaged in the popular new consensus of modern science, and so made unavailable in the debates on what to do with the

vast power of modern technology. Becoming so absorbed with

data and rules, losing sight of there being a world of independently responding

things beyond explanation,

becomes responsible for our building this odd and inexplicably unsustainable

world. We designed it to become ever more reliant on using up scarce resources.

Indeed!

how else could one explain it? Well, the far more

practical way. If that matters, of course, the more practical way is to accept physical reality as something that

needs exploring, but not explaining. Our ideas about it

may need explaining, of course, but reality never does. That is the

view that was firmly dismissed and disparaged in the popular new consensus of modern science, and so made unavailable in the debates on what to do with the

vast power of modern technology. Becoming so absorbed with

data and rules, losing sight of there being a world of independently responding

things beyond explanation,

becomes responsible for our building this odd and inexplicably unsustainable

world. We designed it to become ever more reliant on using up scarce resources.

That easy but impractical leap of faith, that nature is our dream, also becomes responsible for our following the inexplicably unsustainable single

rule and design principle of maximizing the accelerating speed of

development, trying to stabilize adding by %'s, a perpetual explosive expansion

as our idea of 'growth', instead of growth toward creating a comfortable new home on earth. If physical reality

doesn't exist, and the only "reality" is your own ideas of it, a maximum

rate of growth

in wealth is clearly the best choice you can explain!

All

the popular "main stream" thinkers agreed, that the best of all choices would be

to maximize the % rate of increasing profits for the people making the choices!If they were the least bit embarrassed by the curious self-serving quality of

that, they hid it well in other explanations. Now, with the

collapse, we are finding out just how misguided that plan was, steering our peak

century of economic development only with maximum accelerating expansion.

Now we end up with more than a little to explain, of course, as to how we

managed to think that way, and what looks like a painful long term process of

triage.

Why

did we use up our resources building a world that would run out of

gas, and we'd need to rebuild to maintain our culture? Well,

hopefully, it was so we'd finally figure out what doesn't need explaining, but

exploring. This 'debate', or more aptly 'struggle with our own

minds' about what is real and what is imagination, seems to have been going on

since humans first had imaginations. I've looked at some of the cultural,

anthropological and paleontological records to try to figure out when that was,

and to try to imagine the circumstances. The early horizon of human

culture and our history of abstract thinking is being pushed back to 77,000 years now, with evidence of

symbolic scratches in ochre as evidence (3). I think

the evidence is that complex human culture, and so abstract thinking too, go

back considerably further. To me the expressiveness of our

faces, quality of our vocal chords in making sound, and the freedom of

expression in our body movements to dance, indicates we had a lot to say very

long ago, perhaps to the earliest of distinctly human ancestors,

either 1 or 4 million years ago depending on how you look at that.

Why

did we use up our resources building a world that would run out of

gas, and we'd need to rebuild to maintain our culture? Well,

hopefully, it was so we'd finally figure out what doesn't need explaining, but

exploring. This 'debate', or more aptly 'struggle with our own

minds' about what is real and what is imagination, seems to have been going on

since humans first had imaginations. I've looked at some of the cultural,

anthropological and paleontological records to try to figure out when that was,

and to try to imagine the circumstances. The early horizon of human

culture and our history of abstract thinking is being pushed back to 77,000 years now, with evidence of

symbolic scratches in ochre as evidence (3). I think

the evidence is that complex human culture, and so abstract thinking too, go

back considerably further. To me the expressiveness of our

faces, quality of our vocal chords in making sound, and the freedom of

expression in our body movements to dance, indicates we had a lot to say very

long ago, perhaps to the earliest of distinctly human ancestors,

either 1 or 4 million years ago depending on how you look at that.

So rather than blame abstract thinking, I

think the better sign of the time when we began to confuse conceptual

thinking and reality is when that became a serious problem. When we got so good at conceptual

thinking we could get completely lost in it, and started to build great

societies that collapsed. That's seems to be one common thread tying

together all the leading explanation for why complex civilizations collapse,

that our way of expert problem solving has often somehow created problems our

civilizations couldn't solve.

I think we run into problems we can't solve by trusting the world in our minds more

than the one on which we depend (4) and recognizing both

realities would help.

Perhaps the first of these great disappearances of complex technological

societies coincides with the missing link between the several scattered

Indo-European languages Indian/Iranian, Armenian, Hittite, Greek, Italic,

Slavonic, Germanic, Albanian, Baltic & Celtic plus an "outlier" with

no daughter languages, named Tocharian. What is clear is that the western

language group had a common root, the origin of western sentence structure and

arithmetic. That first civilization where complex societies and their

great failures originated is apparently "missing", to be called only Indo-European.

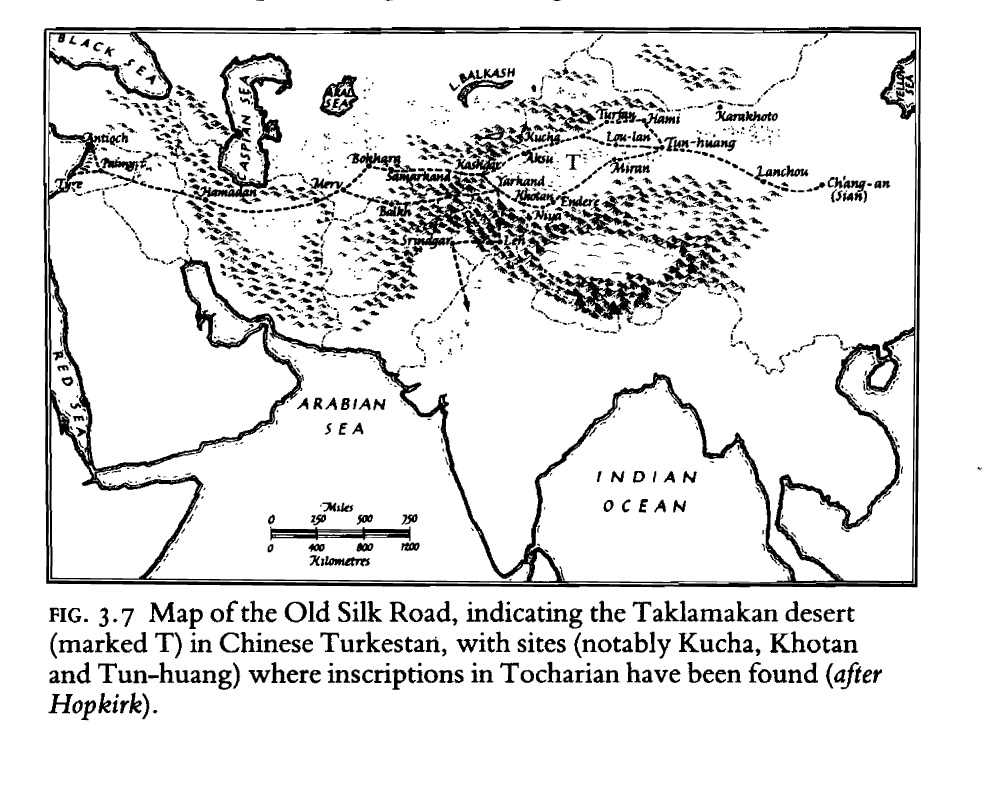

Scattered details allow one to speculate that the common origin might have been

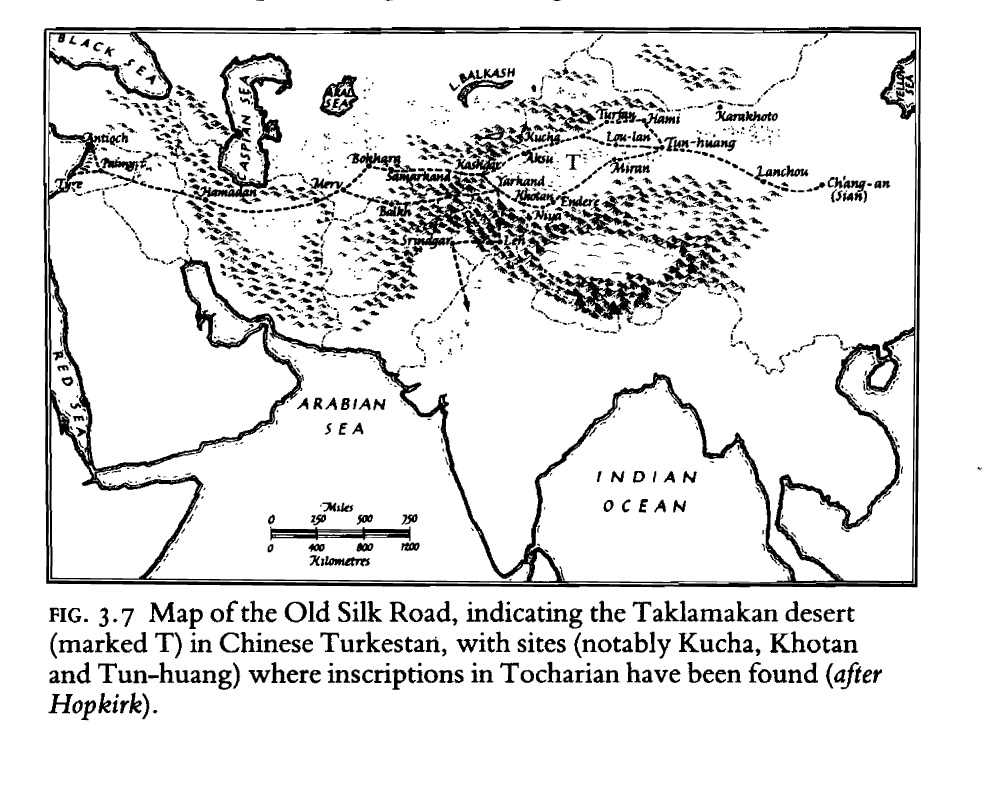

in the isolated urban cultures where the great dessert of Sinkiang is now,

presently some of the most forbidding and unfrequented terrain along the

original silk route between the Mediterranean and China. For this I

had some help from Jane Jacobs, the urban anthropologist and critic.

There are a

series of oases along the south edge of the dessert, fed by water from the Altyntagh Mountains where thriving urban cultures appear to have come and gone

over and over, along that first "interstate highway" of ancient civilization.

That makes it a perfect setting for the original crucible of urban design and

social technology, born in the way speculated about by Jane Jacobs, with her

surmise that such trading villages were where the first "killer app" of the

social organization and machine technology, systemized farming, was developed

(5). What brings attention to that particular

dessert and it's fringe is that it is where inscriptions in an extinct language

were found, seeming to have elements of the other Indo-European languages, that none

of the others have in common. The so called 'Tocharian'

language (though probably misnamed) could then be a remnant of the missing common

origin of the Indo-European languages (6).

Whatever the common origin of the otherwise disconnected roots of the great ancient western

languages, it seems it did vanish without trace and produced a great scattering

of others that became western culture. That seems like a perfect fit,

though just speculation really, if it was also the first case of an advanced

human civilization to fail dramatically, producing a tower of Babble and self-destruction

from

it's own organizing principles. So many other advanced civilizations

have come and gone since, many apparently from some disease of their own notable

success. It's original mother tongue was implicitly the language of the first

major western civilization, and implicitly the first major complexly organized society,

leaving its trace by disappearing without a trace, except for it's scattered

descendants.

1) JM Keynes 1935 The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. Ch 16

2) Kenneth Boulding 1950 A Reconstruction of Economics. Ch 17

3) Michael Balter. 2009 The origin of Art and Symbolism. Science p709-711

2/6/09

4) Alfred Toynbee said "people run into problems they can't solve" and JA

Tainter (1988 The Collapse of Complex Societies) described several

vanished complex societies that persisted with strategies having diminishing

returns that had started with multiplying returns.

5) Jane Jacobs 1968 The Economy of Cities, 2000 The Nature of Economies

6) Collin Renfrew 1987 Archeology of Language, describes the search for the

origins for the common link between the major Indo-European languages

Synapse9

jlh

Indeed!

how else could one explain it? Well, the far more

practical way. If that matters, of course, the more practical way is to accept physical reality as something that

needs exploring, but not explaining. Our ideas about it

may need explaining, of course, but reality never does. That is the

view that was firmly dismissed and disparaged in the popular new consensus of modern science, and so made unavailable in the debates on what to do with the

vast power of modern technology. Becoming so absorbed with

data and rules, losing sight of there being a world of independently responding

things beyond explanation,

becomes responsible for our building this odd and inexplicably unsustainable

world. We designed it to become ever more reliant on using up scarce resources.

Indeed!

how else could one explain it? Well, the far more

practical way. If that matters, of course, the more practical way is to accept physical reality as something that

needs exploring, but not explaining. Our ideas about it

may need explaining, of course, but reality never does. That is the

view that was firmly dismissed and disparaged in the popular new consensus of modern science, and so made unavailable in the debates on what to do with the

vast power of modern technology. Becoming so absorbed with

data and rules, losing sight of there being a world of independently responding

things beyond explanation,

becomes responsible for our building this odd and inexplicably unsustainable

world. We designed it to become ever more reliant on using up scarce resources.

Why

did we use up our resources building a world that would run out of

gas, and we'd need to rebuild to maintain our culture? Well,

hopefully, it was so we'd finally figure out what doesn't need explaining, but

exploring. This 'debate', or more aptly 'struggle with our own

minds' about what is real and what is imagination, seems to have been going on

since humans first had imaginations. I've looked at some of the cultural,

anthropological and paleontological records to try to figure out when that was,

and to try to imagine the circumstances. The early horizon of human

culture and our history of abstract thinking is being pushed back to 77,000 years now, with evidence of

symbolic scratches in ochre as evidence (3). I think

the evidence is that complex human culture, and so abstract thinking too, go

back considerably further. To me the expressiveness of our

faces, quality of our vocal chords in making sound, and the freedom of

expression in our body movements to dance, indicates we had a lot to say very

long ago, perhaps to the earliest of distinctly human ancestors,

either 1 or 4 million years ago depending on how you look at that.

Why

did we use up our resources building a world that would run out of

gas, and we'd need to rebuild to maintain our culture? Well,

hopefully, it was so we'd finally figure out what doesn't need explaining, but

exploring. This 'debate', or more aptly 'struggle with our own

minds' about what is real and what is imagination, seems to have been going on

since humans first had imaginations. I've looked at some of the cultural,

anthropological and paleontological records to try to figure out when that was,

and to try to imagine the circumstances. The early horizon of human

culture and our history of abstract thinking is being pushed back to 77,000 years now, with evidence of

symbolic scratches in ochre as evidence (3). I think

the evidence is that complex human culture, and so abstract thinking too, go

back considerably further. To me the expressiveness of our

faces, quality of our vocal chords in making sound, and the freedom of

expression in our body movements to dance, indicates we had a lot to say very

long ago, perhaps to the earliest of distinctly human ancestors,

either 1 or 4 million years ago depending on how you look at that.