The

#1 sustainability issue in the world

today?

Jessie Henshaw

11/15/09, 9/2/10, 1/6/11

Condensed from recent work

Our love and affection for the earth helps make us creative

problem solvers,

... but something is making us dodge big ones too.

We've let the conversation become conspicuously quiet on some of our greatest

problems. This is about one, how using efficiency to reduce environmental

impacts generally accelerates economic growth and resource use, accelerating our

impacts instead. It seems the root error is that what makes

efficiency profitable is letting you use less of one resource to have more

access to others. That does "create resources" *for the user*... BUT

only in the sense of creating new access to resources, and so accelerates their

depletion elsewhere on the earth. The "trick" our minds play on us

is confusing our subjective view (efficiency creates resources) with a global

view (efficiency accelerates depletion), because of our cultural neglect of

"systems thinking". (1/7/11)

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. urged us to not be bystanders in our own lives,

saying:

Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter."

Because we didn't understand that *local and global views are opposite for

many things* and we don't "follow the money" to check... our way of acting

in our self-interests has been a major source of the conflicts between people and nature instead of relieving them.

We've been trusting the wrong solutions, blinding ourselves to the great moral and practical

problems that have to be faced to bring an end our need for growth.

The problem with

our concept of

I = P • A • T

is that it's really

I = P • A • T•

S

a linear equation missing the hidden

'S' for productivity

STIMULUS, the main

purpose people use efficiencies for

making P • A = f (T, E)

reflecting

how

People use

Technology

to consume

Environment for

making Affluence

and more People

Efficiency is being

used for sustaining growth, not the earth,

Trusting it to reduce our impacts also keeps us from facing the great moral and practical

problem, of

...how to end the need for growth.

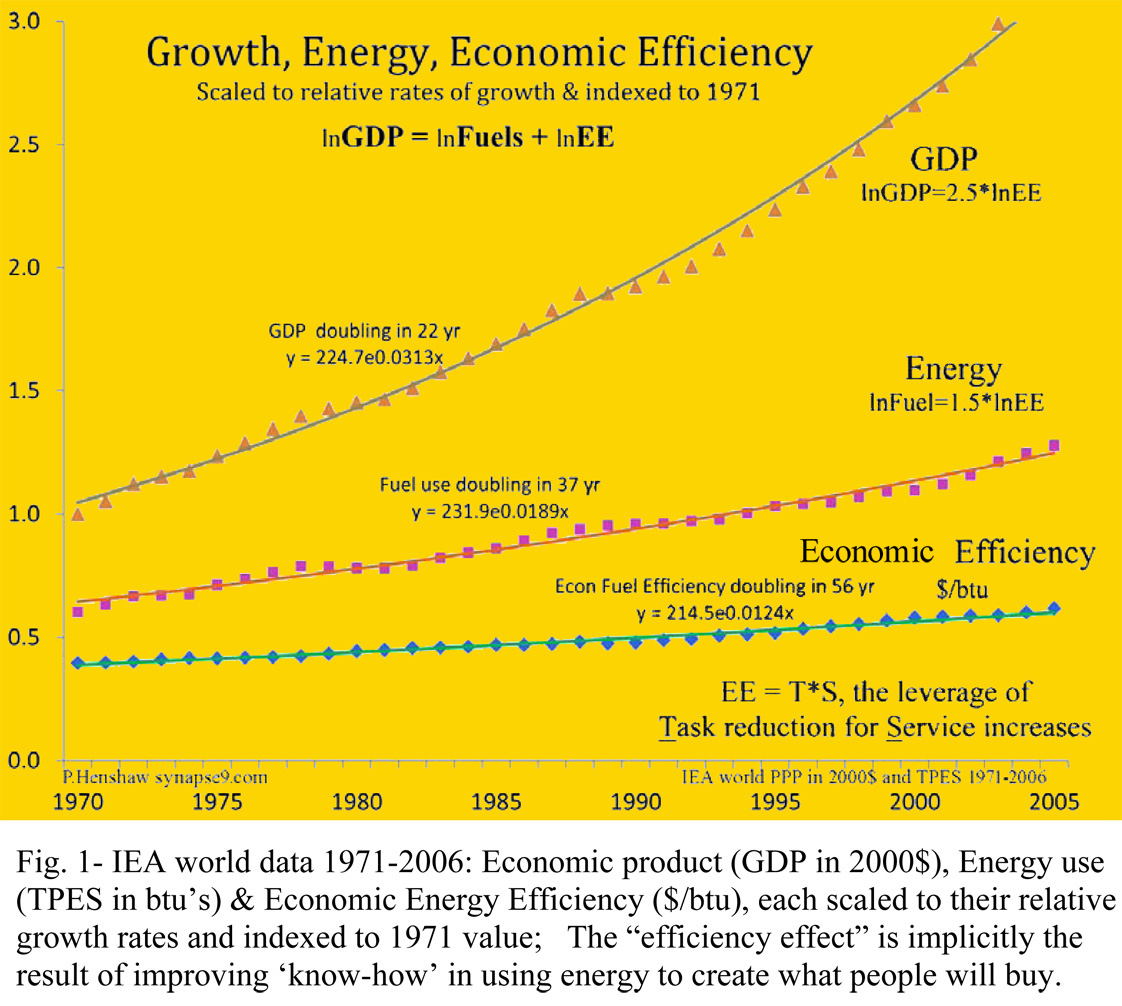

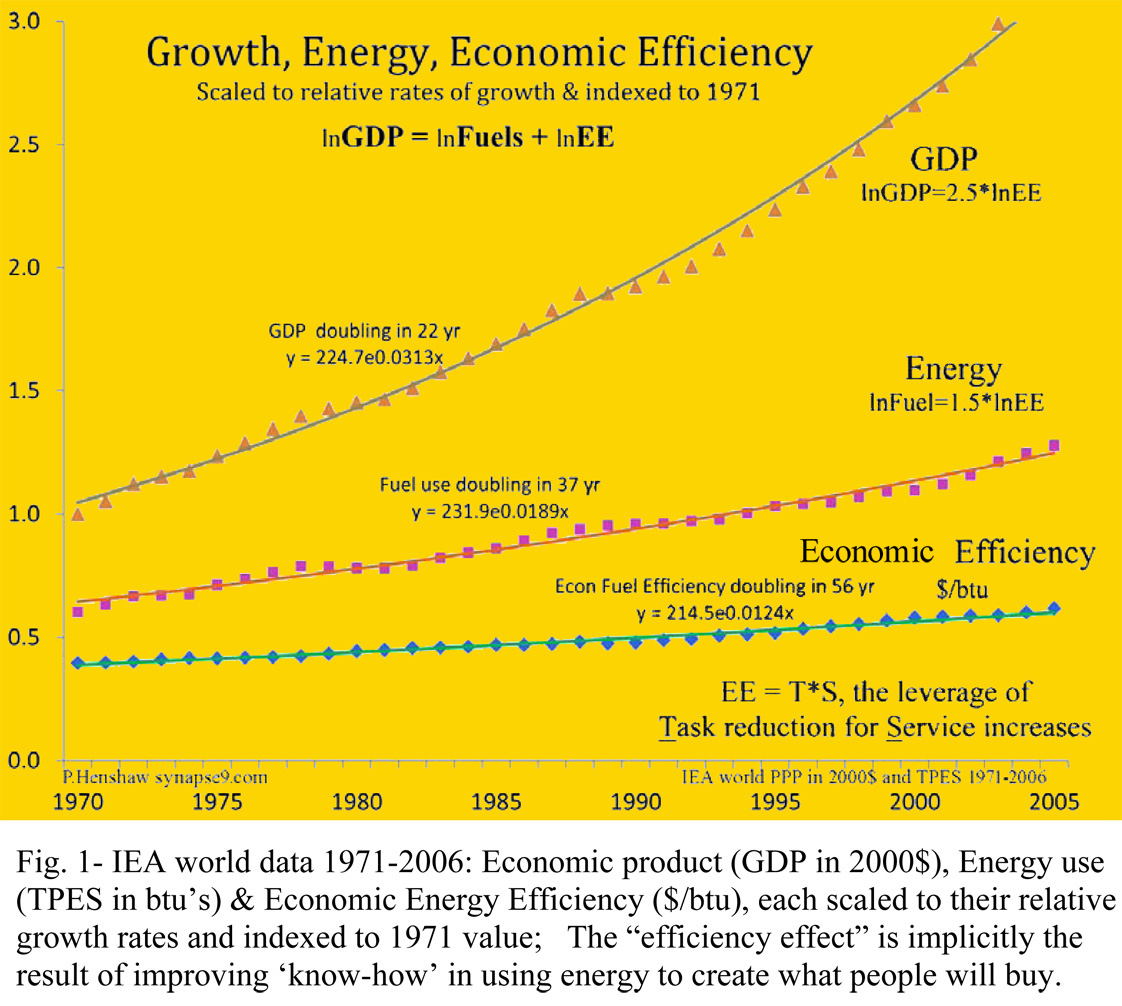

9/2/10The

curves at the left demonstrate

the oddly ignored 150 year old observation of Stanley Jevons, that

improving efficiency results in accelerating resource use.

He first noticed it in how improving efficiency for steam engines used

up coal faster. The problem is we mostly use efficiencies to

simplify our tasks and so make resource use more profitable, to become

more affluent. The "secret" of how it works is that the

particular efficiencies we choose to invest in are the very ones that

for a small cost have the effect of simplifying a whole system of parts,

often with improved technology. That causes an increased

productivity of the whole greater than the decreased needs of the more

efficient part. That's called growth, the redesign of

production systems so they can use and consume more.

9/2/10The

curves at the left demonstrate

the oddly ignored 150 year old observation of Stanley Jevons, that

improving efficiency results in accelerating resource use.

He first noticed it in how improving efficiency for steam engines used

up coal faster. The problem is we mostly use efficiencies to

simplify our tasks and so make resource use more profitable, to become

more affluent. The "secret" of how it works is that the

particular efficiencies we choose to invest in are the very ones that

for a small cost have the effect of simplifying a whole system of parts,

often with improved technology. That causes an increased

productivity of the whole greater than the decreased needs of the more

efficient part. That's called growth, the redesign of

production systems so they can use and consume more.

To achieve the opposite effect

and be responsive to our strains on the environment we'd need to bring

growth to an end, rather than accelerate it with more efficiency...

We've let ourselves be misled, in part, and stumbled into a natural

misunderstanding much like early doctors who applied leaches to remove a

patient's "bad blood". By believing that sort of myth for

too long we're now slipping into grave danger of creating

development we'll be unable to either maintain or replace, instead of

"winning the war with nature", causing a physical system bankruptcy of a

lasting kind.

The love and affection people feel

for the earth, and all their

devotion to the task of doing things right, is being disserved by what

seems to be deeply uncritical thinking. One can also see it as a

natural handicap to overcome, how our minds misuse knowledge so very

easily. We only understand things by constructing our own story

about them, and treat that as reality. We can't help

it, and construct our stories using the myths of our own culture.

Myths sometimes grow and spread like rumors with no foundation at all,

and sometimes stop meaning the same things when the world itself

changes. A great many of our cultural myths no longer mean

what they once did, since we began to collide with successive limits of

the earth ~100 years ago. Expanding opportunity

carries with it increasing conflict, is one of them, and our culture is

founded on the idea of ever expanding opportunity.

It takes

being highly objective to distinguish between realities of nature and

the stories we make up for ourselves, though. Seeing the

above curves shows you something nature is evidently making sense of

somehow, her way, that conflicts with our ideas. What

we don't understand is a rather good pointer to physical reality, since

we evidently didn't make it up, and nearly all our own understandings

are actually stories we made up to fit our own cultural myths.

If it's important, how nature makes sense of things that we can't, is

what we need to stretch our minds to fit around.

It's how our economy naturally works

that makes using efficiency for reducing resource impacts have the

opposite effect. It's been

called Jevons' "paradox" because we don't see how the whole system

becomes more productive by reducing the costs of strategic individual

parts. It's been fairly widely discussed though.

People have just acted as if inhibited in thinking about it, and not taken it to heart, not

even to refine their thinking about how to save the planet from our

accelerating overconsumption.... Even scientists mostly ignore how

the real effect on the economy completely contradicts most

recommendations for what to do. So the whole issue,

staring us in the face, is being quite ignored by educators, activists,

the media and government and seems not to be a focus of any large scale

effort in organizing, planning or research. We seem to not have started

raising the deep moral and practical problem, that our economy responds

to increasing efficiency by digging our society into an ever deeper hole

to climb out of. Partly it's our belief in productivity as a

way to solve problems, when our problem now has become being too

productive in using the earth.

It's also a remarkable story about

our cultures of knowledge, and how people frequently develop

disconnected stories for what they think are disconnected issues, unaware of

connections in the physical world. It

happens

partly because it's easy to think by snap judgments, and to create

cultural realities by popular social agreement.

For how to achieve sustainability it seems much of the social networks

act as if the earth will respond to our love and affection alone,

treating social group cohesion as trumping critical thinking and closely

observing environmental responses. Somehow even modern economists

don't seem to mention that efficiency has always been understood as a

primary growth stimulus, and that it would fail entirely as a strategy for reducing

"externalities" like the use of primary resources for growth.

In part that's because economists treat quantitative physical

measures (rigidly constrained by the conservation of energy), as

limitlessly adjustable qualitative measures of value, so their

recommendations are adjustable too. Numerous other

professional and popular views interpret the quantitative physical world

with their own separate cultural value system too, almost as if treating

the physical world as not even existing. Someone needs to

research the full story of these resulting confusions. It's both important intellectual

history and critical for getting to the bottom of why we

let our main solution for relieving our impacts on the earth be a direct

multiplier of the very problem we intended to solve.

Sustainability

does need efficiency, just not for sustaining our system of ever growing

resource use. It sadly does mean that the central tenet of

sustainability has the opposite of the intended effect on our

environment. The recent history of how the mistake in thinking spread seems to start in the language

used for

sustainability plans, limiting the cost of resource conservation to what is

affordable while meeting growth targets. The CAFE mileage

standards are a good one there, and the energy codes. People

interested should check and see how it is phrased, carefully reading the introductions to

plans for conserving resources, ending climate change or making the transition to renewable

resources or limiting population, etc. They're virtually all

predicated on sustaining growth and expanding the limits of development. Look for the phrasing

promising that improved efficiency will continue to promote growing

prosperity. Then look at the curves, above.

Then look at your world. Then go back and look at the text,

and at the curves again. Then ask if we should continue

accelerating the problem.

The modern source of the confusion

appears to have been

the Brundtland Commission definition of sustainability.

It seems to have been set up for the technical interpretations that

followed, using a twisted meaning for the word "decoupling" to

describe how to make more money and save the earth at the

same time. It dramatically altered the definition of

sustainability, changing it from being a statement of absolutes to a

qualitative measure meaning the opposite. It became a

promise of "best effort" relative to maintaining acceptable rates of

real growth. It appears the OECD in its role of defining

world economic policy was just "doing its job".

Technically, sustainability is now defined as money growing faster than

the apparent costs of impacts. If you don't see how

that completely devoids the original intent and meaning of

sustainability, go

back and read the last sentence carefully, and think. It assures that all kinds of impacts

needed for growth will keep increasing ever faster, even if intended to

be at

marginally slower rates of increase than the money someone is making

from them. The

only way to stop adding to our impacts is to stop adding to them,

of course, in quantitative not qualitative terms. Slowing a rate

of acceleration is NOT deceleration. Really!

What has to change is how investors see

the purpose of their role in choosing how to change the parts of our

economic system. It is investors who choose what to physically

turn our world into, by what additions and replacement parts for the

system they choose to invest in. They need to accept their

natural fiduciary responsibility to preserve the system they are hoping

to profit from. That's the environmental commons with no

owner we all share. Their obligation is to make choices that

steer the economy toward reducing its physical burden on the earth, and

away from our otherwise approaching threshold of exhaustion.

We're a long way down the road to the latter as the now dramatic

explosion of diverse global and interdependent environmental, financial

and social crises clearly demonstrates. Investors need to

actually use their profits from investments to actively prevent the

continued undermining of our whole investment in the earth.

We're a long way from understanding what physically sustainable

investment is, though. It starts with the rudiments of

how to use

money as a quantitative physical measure of impacts, then

needs us to understanding how to copy sustainability techniques from

natural system economies and address the

related difficult financial issues.

We need to see our moment in history

as one of our society changing form, as organisms are often seen doing

to reach their next phase of development at the end of the preceding

one. How so many other complex societies before ours have

failed to progress that way is ample demonstration of the hazard.

If we don't address the real challenges before us, but just keep making

growth more efficient till our options for change are exhausted, our

complex society will more or less abruptly vanish at some not distant

point in time, as relatively small failures of parts cascade to become

the ultimate end of the whole, as happened for the others.

"Our lives begin to end the day

we become silent about things that matter." Martin Luther King Jr.

Those able to see these errors

need to be employed in helping guide the change. We need to fix this, and

other fatal errors still part of our thinking. ( please

help

)

Everyone

seemed pleased with my presentation on "Why Efficiency Multiplies Consumption" at the BioPhysical Economics 09

meeting in Syracuse on 10/17/09. The slides and lecture notes are at

EffMultiplies.htm.

The long paper on the how cultural wisdoms get misled and how to use the what

nature does simply to connect our disconnected languages is

The curious case of Stimulus as Constraint. Other

general discussion: Why our

work ethic has become an endless steeper climb

What

in the world is really going on here?, What we need

to understand to change it

Peak Zucchini !

.. and earlier but good short articles tie

Inside Efficiency

to

How We get out of here?

Lists of other top systems

theory issues and

sustainability issues

jlh

9/2/10The

curves at the left demonstrate

the oddly ignored 150 year old observation of Stanley Jevons, that

improving efficiency results in accelerating resource use.

He first noticed it in how improving efficiency for steam engines used

up coal faster. The problem is we mostly use efficiencies to

simplify our tasks and so make resource use more profitable, to become

more affluent. The "secret" of how it works is that the

particular efficiencies we choose to invest in are the very ones that

for a small cost have the effect of simplifying a whole system of parts,

often with improved technology. That causes an increased

productivity of the whole greater than the decreased needs of the more

efficient part. That's called growth, the redesign of

production systems so they can use and consume more.

9/2/10The

curves at the left demonstrate

the oddly ignored 150 year old observation of Stanley Jevons, that

improving efficiency results in accelerating resource use.

He first noticed it in how improving efficiency for steam engines used

up coal faster. The problem is we mostly use efficiencies to

simplify our tasks and so make resource use more profitable, to become

more affluent. The "secret" of how it works is that the

particular efficiencies we choose to invest in are the very ones that

for a small cost have the effect of simplifying a whole system of parts,

often with improved technology. That causes an increased

productivity of the whole greater than the decreased needs of the more

efficient part. That's called growth, the redesign of

production systems so they can use and consume more.