Inside Efficiency -

An outline of

its effects on

an economy

that works as a whole

Jevons'

Effect and why improving technology efficiency multiplies energy consumption

notes on a conference presentation 10/17/09

P. F. Henshaw

Our use of efficiency is for making us more productive.

If we

understood just that, it would remove all the confusion.

|

Basic

findings

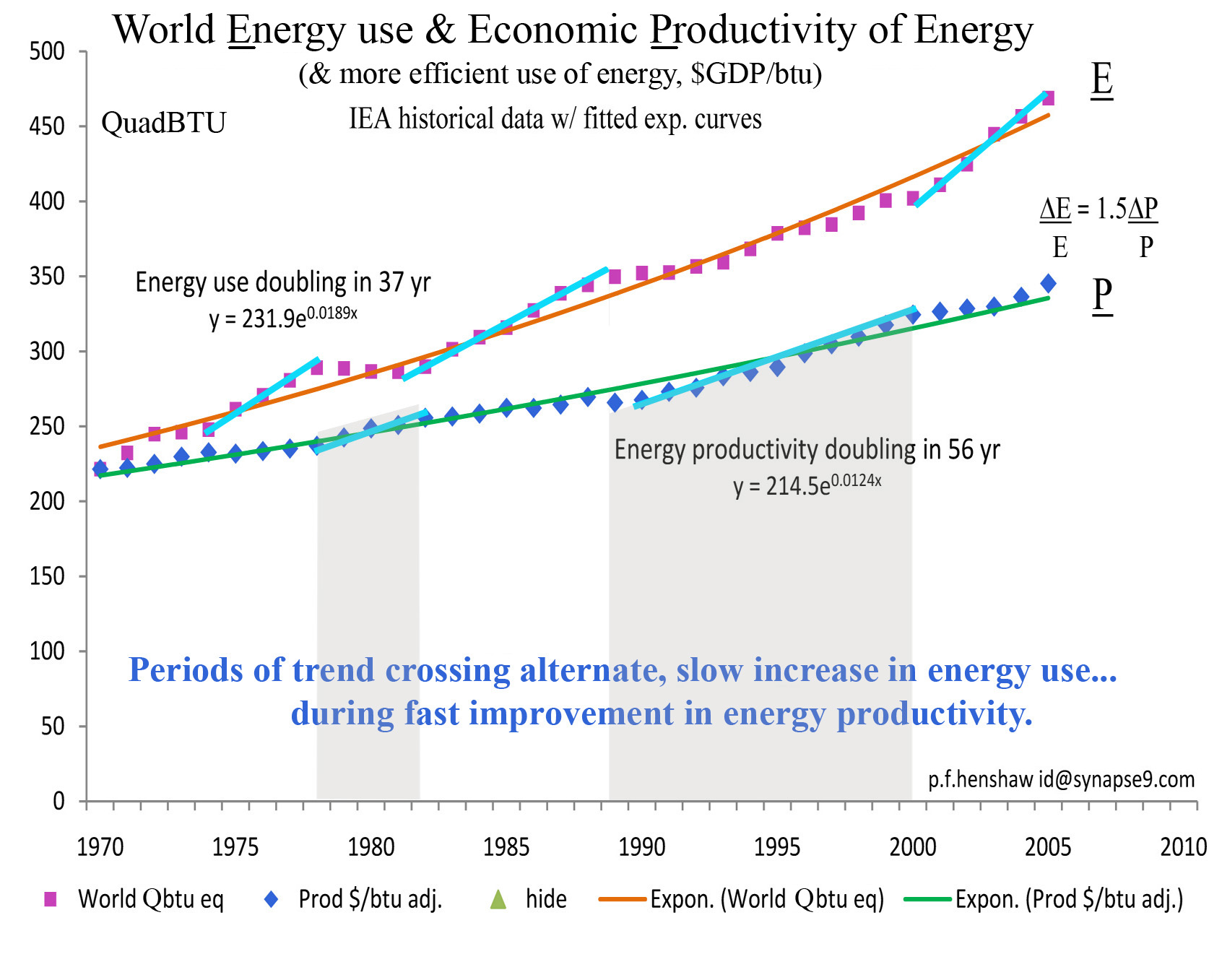

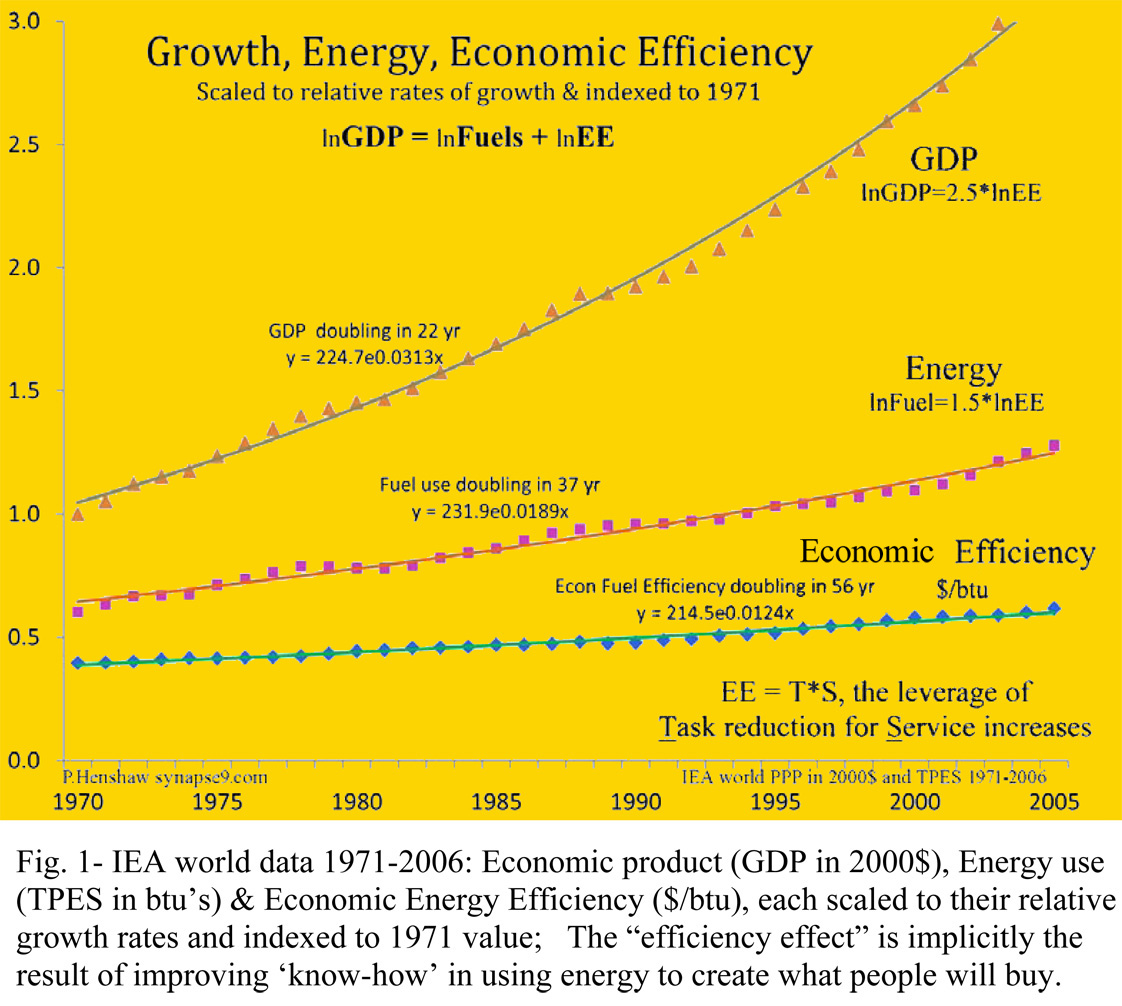

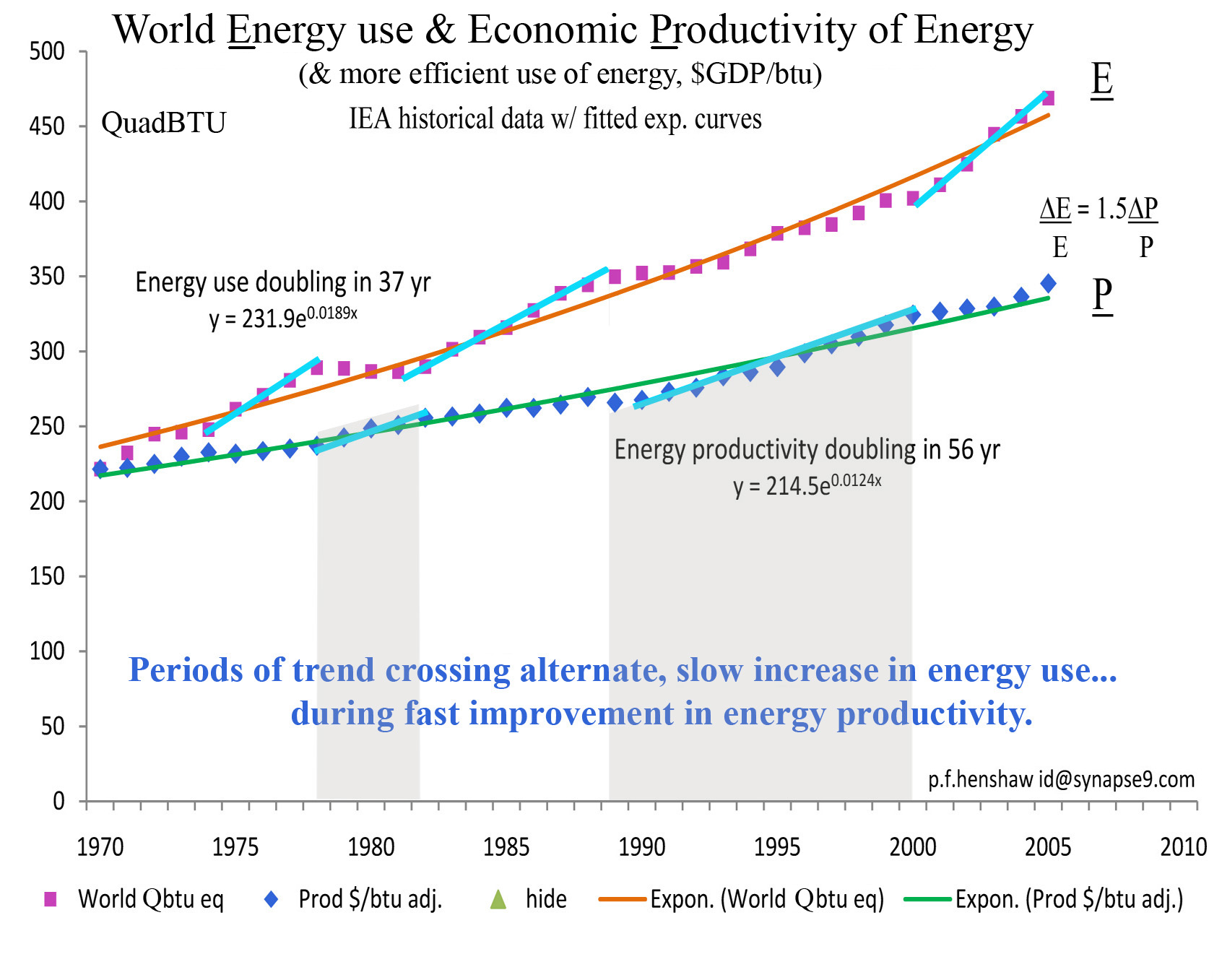

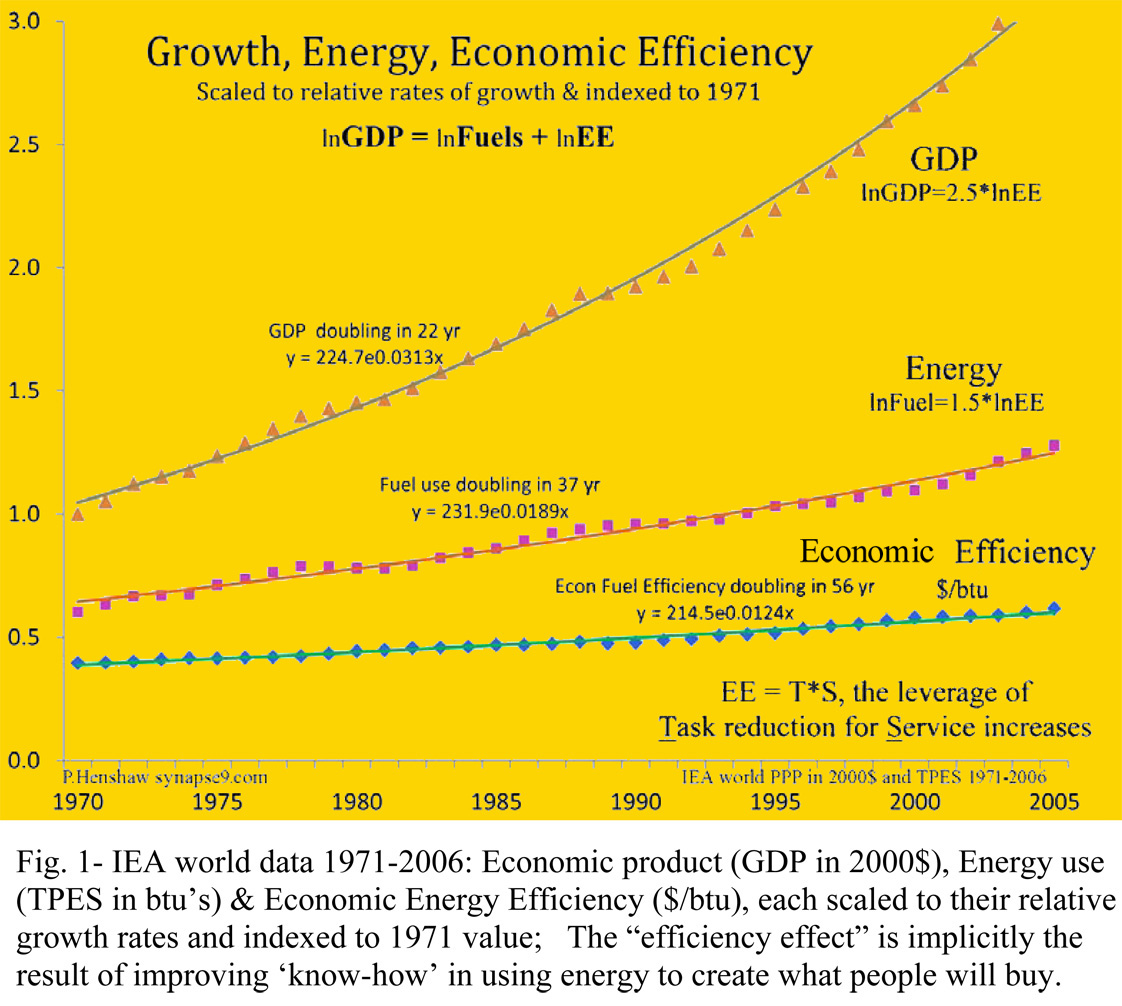

Energy efficiency

improvements and energy use have

both been increasing steadily growing rates. So improving

economic efficiency

apparently enables the creation of more new energy uses than energy

savings. The net effect is to increase the

rate of resource depletion. - (fig 1)

Consequently,

efficiency improvement

results in 2.5 times more energy uses

than energy savings, consistent with the observations of Jevons in

1885. (fig 1) Equally surprising, CO2

is being produced at the same increasing rate as total energy use,

so new clean energy

sources are not replacing any fossil fuel use,

only adding enough to keep the same proportion of clean energy in

the mix as in 1971.

(fig 1) |

|

Why Economic Efficiency Stimulates

Growth & Consumption

23 slide

presentation :

audio (starting from slide #14)

- Oct 2009

meeging,

BioPhysical

Economics 09,

Syracuse NY 10/16-17/2009,

- NY Times coverage

New School of Thought Brings Energy to 'the Dismal Science'

- Dec 2010 The curious use

of Stimulus for Constraint draft paper on the systems

science

- Nov 2011

SEA -

Systems Energy Assessment, the real energy cost of businesses,

resource site w/ links to this and other papers

in Charlie Hall's 2011 EROI collection

- 2008 J.A. Tainter: A history of

Jevons' effect - in Polimeni, Mayumi,

Giampietro, and Alcott: The Jevons Paradox and the Myth of Resource Efficiency Improvements |

Discussion notes

below:

1 - A current interpretation of Jevons'

original finding

1 - Outline of the reasoning

presented

2 - A list

of other interesting effects of efficiency often overlooked

3 - Why I

= P • A • T

a missing a

'• S'

for Stimulus

Blog posts

...If reducing our impacts really speeds them up!! what then??...

+

What in the world is really going on here??

+

Inside

Efficiencies a new short overview of the subject and choices |

|

|

|

|

The data showing efficiency driving growth in general

|

and in detail |

| Fig. 1 - IEA world data

1971-2006: Economic product (GDP-PPP in 2000$), Energy use (TPES in quad

btu's) and Economic Energy Efficiency ($/btu). Each

scaled to their relative growth rates and indexed to their 1971

value. The three curves seem to have a constant average

relation to each other, as if part of very same process. [updated] |

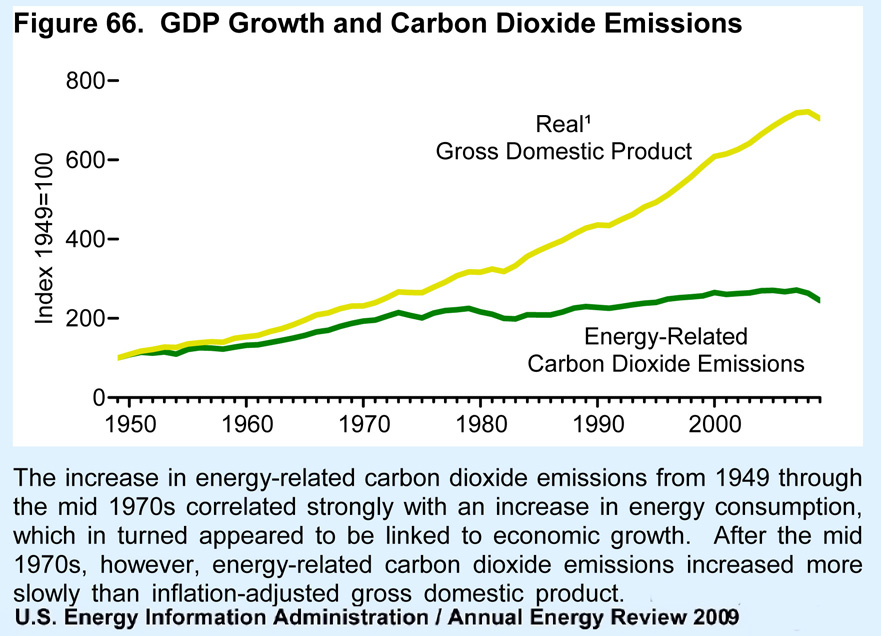

Fig. 2 - Close

coordination between rates of change in world Energy use and

efficiency. Note alternating faster and slower periods than the

trend line. Periods of rapid increase in energy use

coinciding with periods of slower efficiency improvement,

[Same data as Fig. 1, equalized at 1971] [updated] |

|

Business competition drives production,

energy use and efficiency with businesses prospering most when they

are most successful at creating efficiencies that remove barriers to

expanding production better than their competition. Thus

improving efficiency is a principal means of accelerating

consumption. Resources for development go to those

businesses that are demonstrating their competitive edge. |

The data for

the 150 year old "Jevons' effect" for the world economy is clear. As

the economy is presently operating (taken as a "black box" for

energy and efficiency inputs) improving economic efficiency has a

250% rebound effect relative to it's resource use reduction.

Innovations, on average, that save 1.0 gal of gas have the effect of

stimulating more uses equaling 2.5 gal of gas. |

|

|

|

|

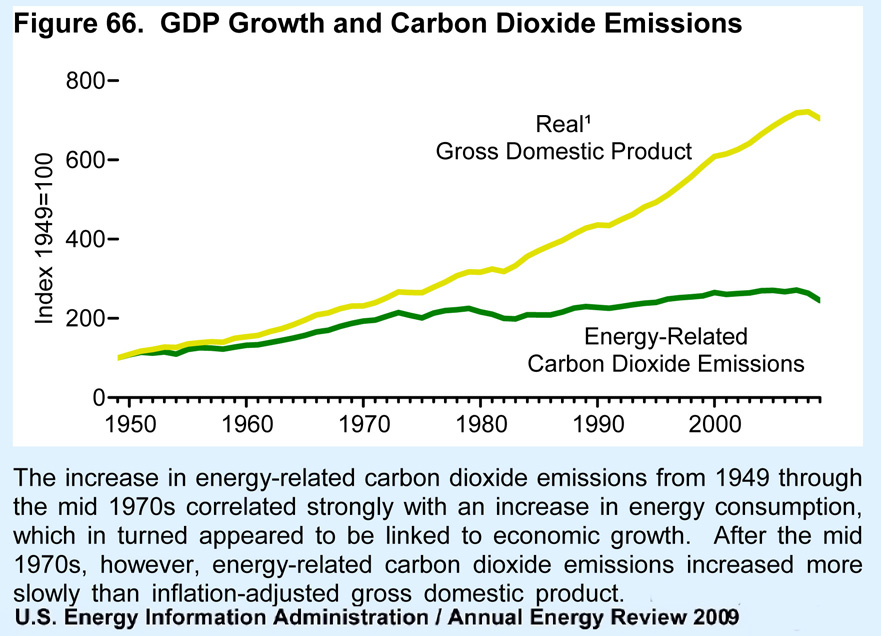

Fig 3. US National Energy

Accounts - Total national energy use leveled off

US energy use shows typical national differences from regular global

relation between energy use and GDP.

EIA

Energy Perspectives 2009 |

Fig 4. US GDP continued

to grow indicating US use of world energy use increased

Energy use per dollar shows trend erased when combined with world

data for relation between GDP and energy use.

EIA

Energy Perspectives 2009 |

| |

|

|

| |

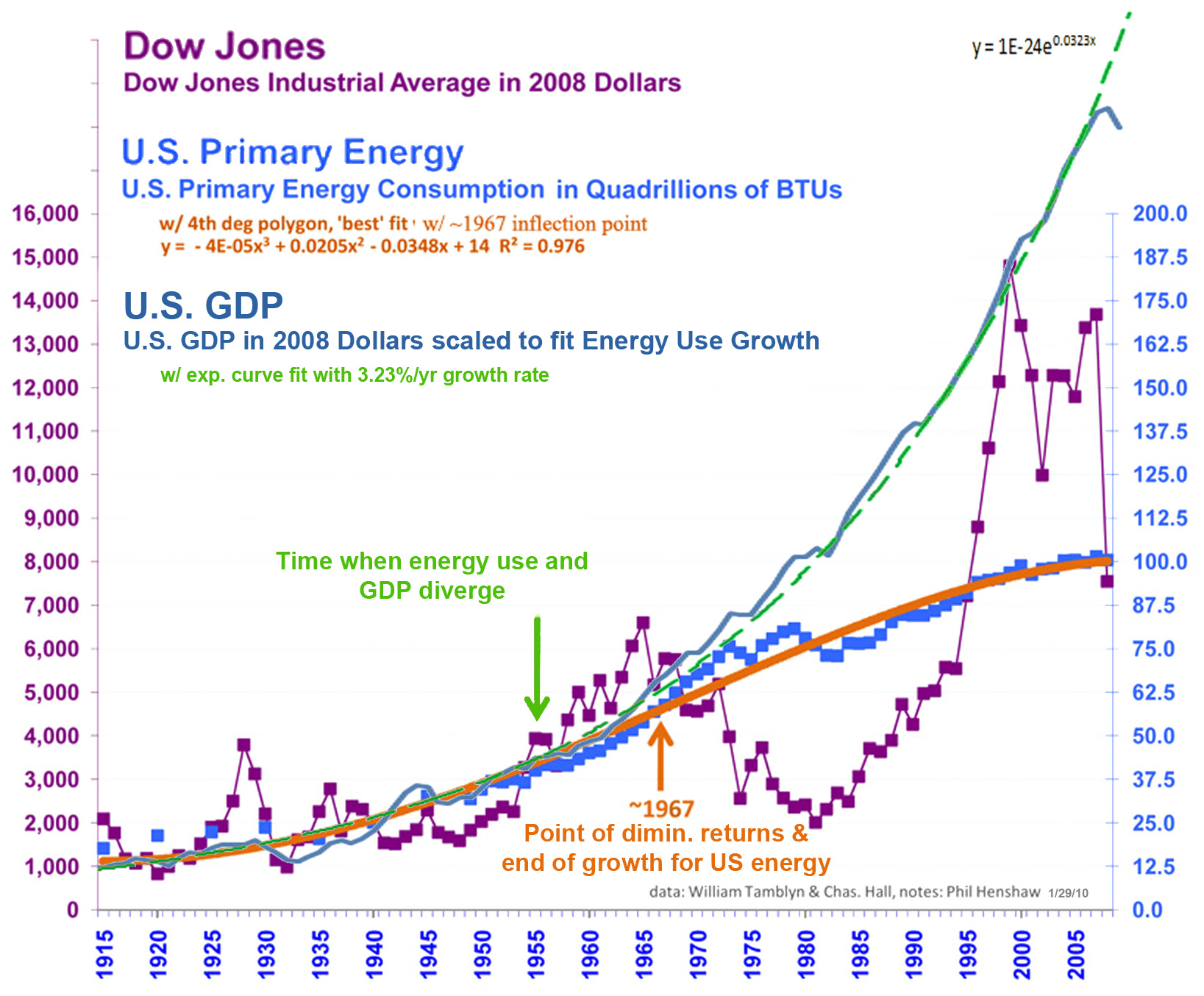

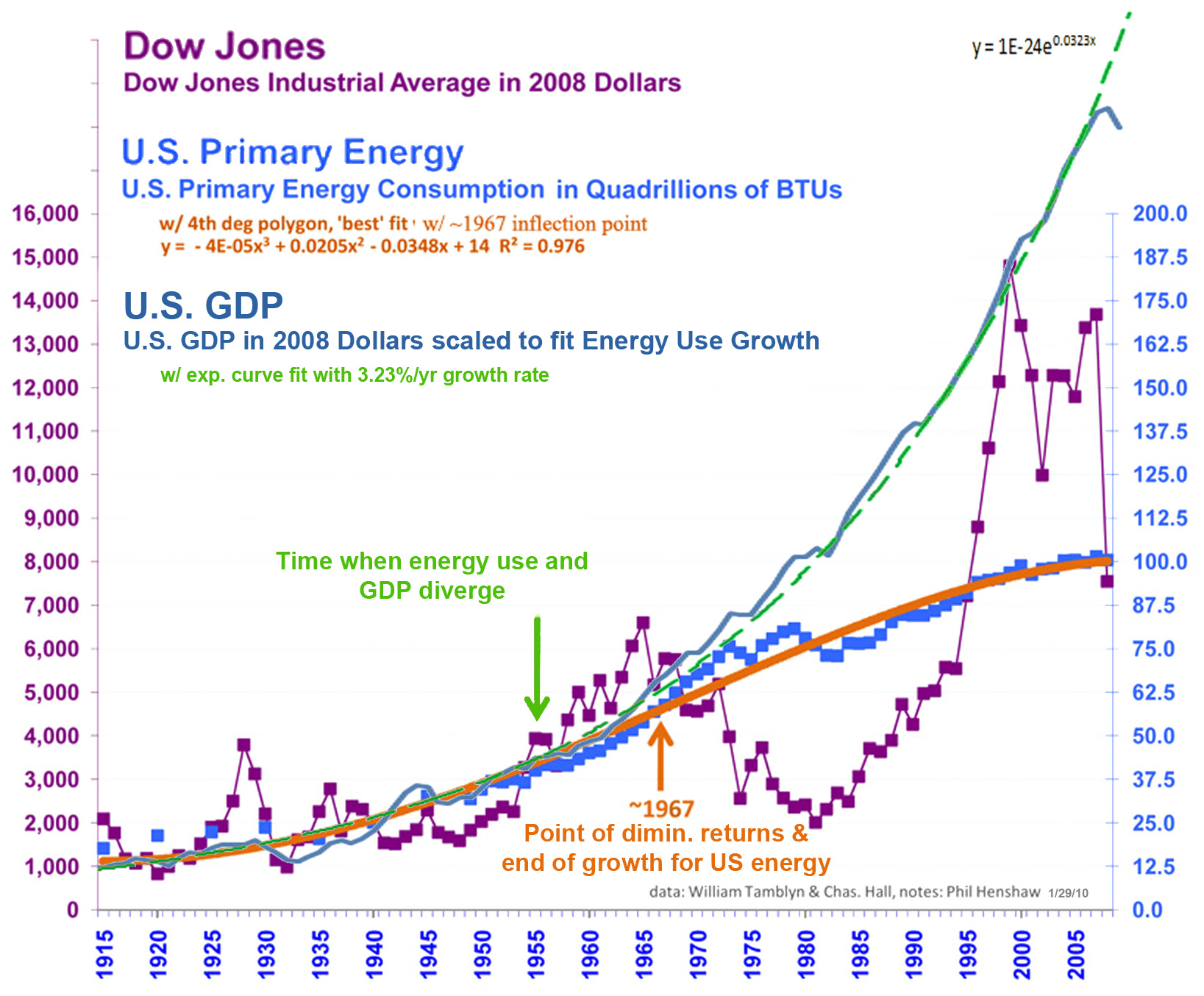

Fig 5. Overlay of US GDP, Domestic Primary Energy use, & the Dow Jones average

The US Stock Market reflected by the Dow Jones

index shows erratic movement while both the US GDP and Primary

Energy use show systematically progressive change, showing the stock

market to be independent of both, and appearing to mainly follow

itself over the long term. World energy use shown in Fig

1 is closely proportional to world GDP. Diverging US GDP may

reflect movement in the measure, independent of the physical

economy, like the stock market appears to have, or relying on

physical productivity that occurs elsewhere, or both. |

|

Regarding Jevons' finding 150 years ago of the 'paradox' that economic

efficiency accelerates resource depletion

(quoting from my 3/23 edit of

the Wikipedia page)

The Jevons Paradox has been used to argue that energy

conservation is futile, as

increased efficiency generally

stimulates other energy uses for a net increase. However, this ignores other

benefits from increased efficiency, such as increased quality

of life. A broad assessment of benefits and liabilities is actually needed.

A global green

tax might directly restrain

energy use as it stimulates improved efficiency, for example, without just

driving energy using businesses to low tax countries. Efficiency without growth

would also extend resources briefly while the adaptation to sustainable

alternatives takes place.

The mental error most frequently made is to not combine the savings of being

more efficient with the expanded footprints of business and economic activity

that efficiencies allow and are often the motivation to start with. To leverage

large returns from small efforts small water conservation measures might be

found to allow increased regional development, for example. In the end that only

increases the number of users and the scale of development with the pressure on

the resource remaining the same. All aspects of how new methods alter their

environment need to be considered.

The economic stimulus effect Jevons first observed might not occur if efficiency

improvements were uneconomic, or if they also reduced the level of incomes

people needed to live as comfortably. Whether that would result in declining

resource footprints while improving the quality of life generally faces the same

questions. Can you discover how to do it and will the new resource potentials

created that way just provide stimulus for business to create growing uses as

usual?

Notes on my Oct 17, 2009 Talk to Charlie Hall's

Biophysical Economics meeting. The notes don't

exactly following the slides. The talk was to systems ecologists, on

efficiency in relation to the ecology of economic systems. If listening to the audio the first

slide discussed is #14 and then back to the beginning. As time runs short

the later slides for raising related subjects are only mentioned quickly.

1 - Why

efficiency improvement makes it easier to use resources and stimulates growing consumption

10/20/09

1.

Basic paradigm – economies as physical learning

systems

a)

Start from physics

first principles … like the conservation laws that imply transient complex

system development processes are required for change

(1)

Representing

natural processes with equations

(a)

neglects the

complex development processes, by which they work.

(b)

neglects their

limits and possibilities,

(2)

how to search for

the great gaps in our models

(a)

physical systems

represented as statistical equations that might recur over and over

(b)

opportunistic

learning processes that occur only once

b)

Start from what’s

naturally missing in the typical “S” curve of development. What’s missing is

the system’s environmental learning process. Slide 14

(1)

Make note of clear

switch in kind and direction of learning at inflection point!!

(2)

from multiplying

returns to dividing returns

(3)

from the past to

the future,

(4)

from pumping up to

fitting in.

2.

The data shows impacts growing faster than

efficiency, as parts of a system working as a whole.

a)

The popular

assumption is that they should go in opposite directions, but they don’t

(1)

Efficiency building

codes, creative innovation strategies, all seem to have the opposite of intended

effect.

b)

Economists have

understood this all along, but it’s mysterious why working with sustainability

planners for years and years they don’t mention that both groups are using the

same solution for opposite effects.

c)

From inside a

learning system, each part learns two things, how to reduce their effort and how

to provide more service.

(1)

Efficiency as a

measure of the “work it takes”

(2)

Productivity as the

same thing, but considered as the “service it provides”

(3)

Decreasing the

"resource it takes" increases "the work the resource can do" so to get the

impact you combine both

(4)

Difference in

looking upstream or downstream in the flows of an opportunistic economic system

3.

Efficiency doesn’t steer systems.

a)

What really steers

the direction of whole system development is what the surplus generated by that

learning is used for, with two main choices

(1)

Using it to fit

into the world,

(2)

Using it to change

the world to fit your image,

b)

Efficiency can

accelerate either,… so efficiency is more like “the gas” and does not work like

a steering wheel

(1)

presently

accelerating our increasing control of nature and maximizing resource

consumption

c)

Our mental and

cultural models of change are radically detached from the nature of physical

processes

(1)

Multiplying change

is not a natural fixed state except in imagination, and nearly all discussion in

our culture treats it as such.

(2)

We built our

institutions around the cultural experience of the former” limitless growth”

period

(3)

financial

information model represents multiplying change as a constant, but accumulates

misinformation after the inflection point ~ 1960

2 -

Inside Efficiency - A

few things about how efficiency changes

systems we often leave out…

11/4/09

1.

Efficiencies that save money or resources create savings that get

used for other things. We tend to count the subtractions but not the additions…

a.

Saved money and energy are like “printing money” and “creating

energy” not previously available, and often used for leveraging other things

b.

Say, a 10 year payback on insulating your house, uses resources to

saves and create resources that didn’t exist before… having a positive EROI

i.

First you have the added energy use and other impacts of the work

ii.

You also free up energy as a resource for others to use for powering other

uses with various impacts,

iii.

After the 10 years you have what amounts to a new source of income for

spending on other entirely new resource uses yourself,

iv.

You’ve also given the bank a profit, maybe equal to half of the cost of the

work, for it to use in multiplying more investments…

v.

the reduced impact you counted is probably equaled by (i & ii) and exceeded

by (iii & iv), thus the growth effect.

c.

When adding up impacts of spending we may count only what we see, and

miss the hidden impacts of the whole system that delivered the goods.

i.

we add up the impacts of the physical processes by which things are

made, and ignore the usually larger hidden impacts of:

1)

the employee, business operation and finance costs and impacts

2)

the embodied business development costs and impacts

3)

the resource depletion opportunity costs

2.

New efficiencies can collapse whole networks of mature technologies,

a.

Free internet media now threatens the model of professional journalism

b.

New technology used by low wage people can deny markets to formerly

well paid people.

3.

Creating efficiencies does determine what other people will use them for

a.

Saving water where that was a supply barrier to development, invites

development, expanded urban infrastructure and demand on all resources.

4.

"Do more with less" is what people want and but also and ever steeper

climb

a.

Matching the efficiencies of competitors is needed to keep investors.

b.

With unlimited resources it has the effect of sharing ways to have more

c.

With limited resources the effect is sharing ways to take more from

others.

5.

Efficiencies are a limited resource that gets ever more expensive,

a.

Finding ever greater efficiencies is a non-renewable resource, with the

same depletion points of vanishing return as diminishing EROI resources. You

can plan on their becoming too expensive to use.

b.

2nd law efficiency limits for technologies and whole systems may only

be seen in diminishing returns on investment for no other apparent cause.

6.

Efficiency has two faces, like Jekyll and Hyde, benefits that become real

dangers, like relying on increasing use of specialization or monocultures.

a.

Increasing control is decreasing tolerance. It leads to loosing

control due to complications that more tolerant designs can overlook.

b.

Environmental adaption benefits from complex diversity. Uniformity

reduces options, adds to inflexibility and instability in response to change.

c.

Accelerating coordinated change becomes accelerating uncoordinated

change due to increasingly narrow learning and delayed response.

7.

Logic makes computers very efficient for problem solving, but needing

perfect inputs to get meaningful outputs

a.

Computers treat complex questions as “garbage

in” to result in “garbage out”.

b. Nature’s way of computing is wasteful in every

step, but takes “garbage in” and produces “fruit and vegetables out” or “garbage

in” with “art and music out” using physical system complexity

as its tool.

c. The ability to sort out

undefined complexities to select what problem needs to be solved, that

computers can't do at all, seems to be an important efficiency too.

The problem with

our concept of

I = P • A • T

is that it's missing the hidden

'S'

for growth

Stimulus

Impacts

on the earth =

Population • Affluence • Technology

efficiency • Stimulus

of increasing productivity

It's

150 year old established science, actually. Why we use

efficiencies is to simplify our tasks and become more affluent.

Our main purpose in improving organization and being more efficient with

our tasks, often with improved technology, is to

increase our productivity. That's a growth stimulus.

That makes using it as a strategy for reducing impacts completely

self-defeating. Over a century ago Stanley Jevons noticed

the effect in England when improving steam engines to use less coal

accelerated the consumption of coal, not the reverse. The added utility

and growth stimulus of

improved technology, and so the productivity of the people using it,

increased the use of the resources it was intended to conserve.

It's

150 year old established science, actually. Why we use

efficiencies is to simplify our tasks and become more affluent.

Our main purpose in improving organization and being more efficient with

our tasks, often with improved technology, is to

increase our productivity. That's a growth stimulus.

That makes using it as a strategy for reducing impacts completely

self-defeating. Over a century ago Stanley Jevons noticed

the effect in England when improving steam engines to use less coal

accelerated the consumption of coal, not the reverse. The added utility

and growth stimulus of

improved technology, and so the productivity of the people using it,

increased the use of the resources it was intended to conserve.

It was called "Jevons' paradox" because it is

counter intuitive. It's been widely discussed too.

People have simply not applied it to correcting our wishful thinking

when it comes to saving the planet from our overconsumption... Though

long recognized by many

scientists, even other scientist don't take it to heart, so it's been completely ignored in the public advocacy for

sustainability by educators, activists, media and government in

organizing,

planning and research. That's trouble! It happened

partly because people normally think by snap judgments, and "go with their intuition".

Here our intuition is dead wrong. Somehow even modern economists

have just never seemed to mention that as

a strategy for impact reduction it fails entirely. Someone needs to

research the full story of the confusion. It's both important intellectual

history and critical for getting to the bottom of why we

let our main solution for relieving our impacts on the earth be a direct

multiplier of the very problem it was intended to address.

Sustainability

does need efficiency, just not for stimulating even more growth. It

sadly does mean that the central tenet of sustainability that people around the

world are now relying on has the opposite of the intended effect on our

environmental. Look at the language of the proposals.

Even the strategies for climate change to reduce CO2 and other GHG

emissions are entirely phrased as plans to improve the

efficiency of growth. Then look at the curve. It only

means money growing faster than impacts. Ot assures that all our

kinds of impacts will keep increasing ever faster too, even if

marginally slower than the money someone is making off them. The

only way to stop adding to our impacts is to stop adding to the economy,

really. That means investors accepting their natural

fiduciary responsibility for choosing what systems the economy will

develop. They'd need to actually use their profits

from investments to no longer undermine the value of our common

investment in the earth, and invest in long term sustainability instead.

That's possible, but means that a fundamental change in the design in the economic system

is needed to make

sustainability physically feasible.

HDS consulting

It's

150 year old established science, actually. Why we use

efficiencies is to simplify our tasks and become more affluent.

Our main purpose in improving organization and being more efficient with

our tasks, often with improved technology, is to

increase our productivity. That's a growth stimulus.

That makes using it as a strategy for reducing impacts completely

self-defeating. Over a century ago Stanley Jevons noticed

the effect in England when improving steam engines to use less coal

accelerated the consumption of coal, not the reverse. The added utility

and growth stimulus of

improved technology, and so the productivity of the people using it,

increased the use of the resources it was intended to conserve.

It's

150 year old established science, actually. Why we use

efficiencies is to simplify our tasks and become more affluent.

Our main purpose in improving organization and being more efficient with

our tasks, often with improved technology, is to

increase our productivity. That's a growth stimulus.

That makes using it as a strategy for reducing impacts completely

self-defeating. Over a century ago Stanley Jevons noticed

the effect in England when improving steam engines to use less coal

accelerated the consumption of coal, not the reverse. The added utility

and growth stimulus of

improved technology, and so the productivity of the people using it,

increased the use of the resources it was intended to conserve.